China Nights is a Radii series featuring stories of crazy, funny, weird and wild after-hours experiences in this crazy, funny, weird, wild place. Hit us up if you have your own story to share.

Let’s cut to the chase about why I’m in China. Not for the love of drinking and getting ripped off by cabbies, nor Chinese girls, nor the culture, nor Communism. All of that’s in New York if you look hard enough. I came for one reason and one reason only: to meet a superhero. And I did.

My search started how any search starts: I walked up and down the street, drink in-hand, boys in-tow. Our mission was straightforward and simple. Find the Batman. We began by looking up, as anyone else would.

When you take in Shanghai’s massive buildings jutting into the smog, you begin to wonder what was underneath it all before. Row houses, richly textured with grey bricks, hardwood and hundreds of years of nightly family-style dinners. Most of them gone now. Replaced by the 30-some-odd story apartment buildings like the one I inhabit.

The process shaping Shanghai’s forest-o-buildings evolution is nothing short of brutal. Those old houses? Bulldozed in the night. Sometimes, in the wee hours of the morning (prime Batman hunting hours). Only skeletons remain of what look like bombed-out structures, with plastic toys, kitchen appliances and other household refuse loosely scattered among the rubble.

Our search took us to one of these boneyards around 4am. We ducked in cautiously, like horror movie heroes that don’t make it. The twists and turns of the alleyways canopied in bamboo scaffolding completely obfuscated the little light there was, and we relied on short-range flashlights from our cellphones. As we advanced a few feet at a time, we illuminated the next few feet of near-collapsing stone walls, carved doorway arches, three-legged chairs and headless baby dolls. Then we heard it.

We could make out heart-beat-faint harpsichord music playing from just a few stories above. It was the original animated, Adam West-era, Batman intro music. Crunching over the broken glass lining the floor, we ran into what looked like a railroad-style apartment. The first room was filled with plastic statues of the Virgin Mary. Two dozen metal hooks hung on rusted chains from the ceiling of the second room, and there were drains in the floor. The third and final room was completely bare except for a solitary blue-plastic chair wedged into the corner beneath a shoulder-width hole in the ceiling.

We legged it up the chair and pulled ourselves onto the second floor. It was even more ruined than the first, and mostly bereft of a ceiling. Though there was more light, the source of the harpsichord Batman theme wasn’t clearly visible. It seemed to be coming from all sides. We tried to follow it the best we could.

Deftly maneuvering around a crumbling, load-bearing wall on the outer face of the building, we shimmied on a ledge a few inches long to reach the apartment window adjacent to the one we’d come up. Climbing through the window, we could see the entire half of this floor was open.

And there he was. On the opposite corner of apartment building, perched on a ledge similar to the one we had just crossed — Batman stood watch over the people of Shanghai.

He was naked except for a pair of boxers, which clung to the sides of his sweaty, thin legs. He had two empty bottles of baijiu next to him, and one more in hand. On his face he wore the legendary, black, pointed-ear mask. I said, “Hello,” but he didn’t speak English and told us to “go the fuck away,” or so I assume.

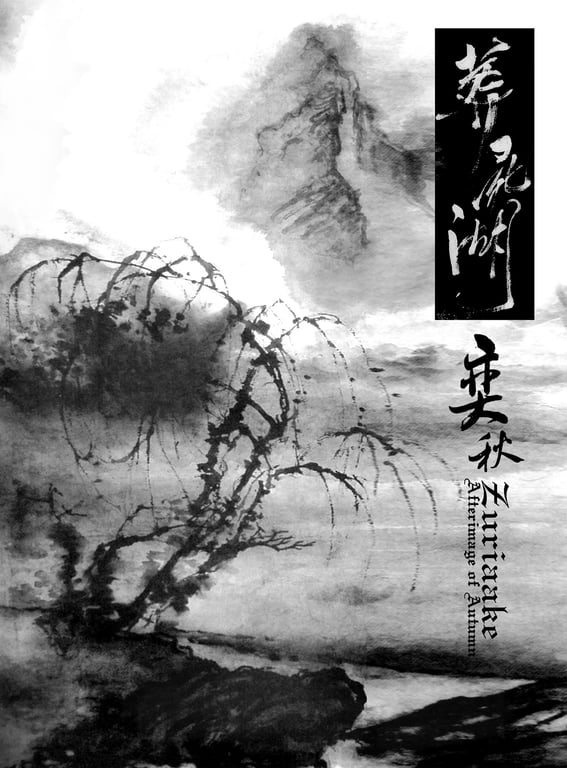

Cover illustration by Marjorie Wang