Walks of Fame is a monthly column where we profile a famous individual from China (or of Chinese heritage) that you should know more about. We introduce you to basketball great Jeremy Lin this month and explore his incredible sporting performance known as ‘Linsanity.’

Linsanity. It’s the linguistic hybrid marking an era in which NBA star Jeremy Lin upended the world of basketball.

It’s the otherworldly performance characteristic of Lin during a period that began in February 2012.

It’s the collective high of fans the world over watching a previously unknown — and different — basketball player go Super Saiyan on the court.

It’s an award-winning film that documented it all.

Linsanity. It’s the single most iconic portmanteau to grace the basketball world since 1891, when James Naismith dropped a ball through a basket and named the sport itself.

Jeremy Lin at an Adidas press conference. Image via Wikimedia

It has been 10 years since the world came to know the name Jeremy Lin. Now 33 years old, the California-born baller played nine NBA seasons with eight different teams before joining the CBA’s Beijing Ducks in 2019.

After a stellar first year in the East (Lin averaged 22.3 points, 5.6 assists, 5.7 rebounds, and 1.8 steals), the former Knicks point guard returned to the U.S. and joined the G League (formerly the D League), the NBA’s official minor league, in the hopes of an NBA renaissance.

Lin was the seventh-highest scorer in the G League, but not a single franchise threw him an offer, making him the only top-ten scorer to secure no contract that season.

When May 16, 2021, came and went, so did Lin’s final opportunity to play professionally in America.

“I’ve always known I need to jump through extra hoops to prove I belong,” he said in a heartfelt message on social media two days later.

“I told myself I just need ONE ten-day contract, one chance to get back on the floor, and I would blow it out the water. After all, that’s how my entire career started — off one chance to prove myself,” he writes.

“For reasons I’ll never fully know, that chance never materialized.”

Lin’s final departure from the NBA can arguably be characterized in much the same way as his journey into the league. He is an undeniable talent, a leader, and a player who will do whatever it takes to level up, but overlooked due to forces over which he has no control.

Born to Play Ball

Jeremy Lin, whose Chinese name is Lin Shuhao, was born in Torrance, California, on August 23, 1988. Lin’s father, Gie-Ming, is of Hoklo ancestry, a people of the Han Chinese ethnic group found in Fujian, Taiwan, and other areas of Southeast China. His mother, Shirley, is also from Taiwan and has roots in China’s Zhejiang province.

Gie-Ming and Shirley immigrated to the U.S. separately in the early ’70s and met as students at Old Dominion University.

The pair raised Jeremy and his two brothers in Palo Alto, California, in a devout Christian household and fostered a competitive spirit in their children from early on, both in sports and academics.

Their father would often take the kids to the YMCA, and they frequently watched old basketball games recorded on the VCR. (Jeremy’s younger brother, Joseph, also plays professional ball in Asia.)

Both worked diligently to support their kids while also regularly attending Lin’s high school games. Shirley was even instrumental in developing a National Junior Basketball program in Palo Alto.

Lin attended Palo Alto High School and captained the basketball team in his senior year, leading them to a 32-1 record and a California Interscholastic Federation Division II state title.

He averaged 15.1 points, 7.1 assists, 6.2 rebounds, and 5.0 steals that season and earned the title of first-team All-State and Northern California Division II Player of the Year.

It was during Lin’s high school years that actor and producer Brian Yang took note of his basketball aptitude. Even then, he saw potential in the young athlete’s story. Yang would later produce the documentary Linsanity alongside Christopher C. Chen and director Evan Jackson Leong.

“I read about him in my local Bay Area newspaper, the San Jose Mercury News. He was front cover of the sports section,” says Yang. “I was like ‘who’s this?’ You don’t see many Asian American kids perform at that level, even in high school.”

Passing the ‘Eye Test’

Despite a phenomenal high school record, no college recruiters gave Lin a second look or offered him a Division 1 scholarship.

He sent a highlight reel to all the Ivy League and Patriot League schools, including neighboring Stanford and his dream school, UCLA, but only received interest from Harvard and Brown.

His appearance was almost certainly a factor: He wasn’t particularly tall or strong, and recruiters lacked a frame of reference for the ostensibly anomalous Asian American player. He just didn’t pass the ‘eye test.’

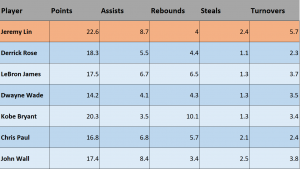

Lin was described as ‘deceptively athletic’ in scouting reports, while fellow 2011 rookie John Wall’s speed and athleticism were said to be ‘freakish’ and ‘explosive.’

“Me and John Wall were the fastest people in the draft, but he was ‘athletic,’ and I was ‘deceptively athletic’… I’ve been deceptively ‘whatever’ my whole life,” said Lin during a 2017 Q&A.

Jeremy Lin goes head-to-head with John Wall. Image via Wikimedia

Lin ultimately joined the Harvard Crimson, and they were happy to have him. But even then, coach Bill Holden never expected what was to come, telling The New York Times: “If I told any other guys on the team that Jeremy’s someday going to play in the NBA, none of them would have believed that.”

But Brian Yang might have. It was during Lin’s time in the Ivy League that Yang first made direct contact with Lin in his freshman year.

“When he was a junior entering his senior session, I was thinking how this would be an interesting story to document,” he says.

He kept in touch with Lin and approached him with a proposal after a game at Yale. Lin was intrigued but hesitant — still a fairly shy and introverted college kid. Yang followed up a few months later but still made no progress.

“By the time we got a response or talked to him again, his whole senior year had passed. So we’re like, “Okay, I guess we’re not gonna be filming with him during college,” says Yang.

Yang told Lin that whatever his career trajectory, they were still interested in his story. Fortunately for everyone, Lin’s career brought him to the big league — eventually.

Lin became the first Ivy League player in history to rack up 1,450 points, 450 rebounds, 400 assists, and 200 steals, but he went undrafted by the NBA.

In Michael Lewis’ 2016 book The Undoing Project, former Houston Rockets GM Daryl Morey acknowledges that Lin should have been a first-round pick. “The reality is that every [expletive] person, including me, thought he was unathletic. And I can’t think of any reason for it other than he was Asian,” said Morey.

Lin did, however, earn an invite to a mini-camp with the Dallas Mavericks, after which he joined their Summer League team.

His performance in the Summer League earned him contract offers with the Mavericks, Los Angeles Lakers, Golden State Warriors, and an unnamed Eastern Conference team. Lin signed with his hometown team, the Warriors.

Lin was the first player to go from Harvard to the NBA since 1954. During his rookie year in San Francisco, he finally agreed to shoot the documentary.

“He later told us, ‘I wasn’t sure I was gonna make the NBA. I don’t know why you guys wanted to film with me. Why was my story that interesting?’” Yang recounts. But from their perspective, “it was like, even if you don’t wind up making the NBA, what you’ve accomplished to this point is remarkable.”

Changing the Game

Representation matters, and as the fourth Asian American and first Chinese American in the NBA, Lin joins a relatively short but impactful list of East Asian athletes to shatter barriers and defy stereotypes in the world’s preeminent basketball league.

The first player in history to break the color barrier in professional basketball was Wataru ‘Wat’ Misaka, a Japanese American who made his modest debut in the Basketball Association of America (now the NBA) in 1947. It was the same year Jackie Robinson became the first Black Major League Baseball player.

Misaka only played three games with the Knicks before he was cut. But like fellow Knicks alumnus Lin, he became a symbol for more than his on-court performance.

University of Utah basketball player Wat Misaka in 1948. Image via Wikimedia

In college, Misaka led the University of Utah basketball team to an NCAA victory — during World War II, in 1944 — a remarkable accomplishment in its own right.

Misaka avoided the Japanese internment camps, but did become a symbol of hope for the Japanese Americans who were less fortunate.

Chris Komai of the Japanese American National Museum told NPR that most people in the camps were aware and proud of Misaka’s accomplishments, particularly since it was one of the few pieces of good news coming from the outside.

Misaka had been following Lin’s career since his Harvard days, and the two finally met at a Rockets vs. Jazz game in 2013. He passed away in 2019 at 95 years old.

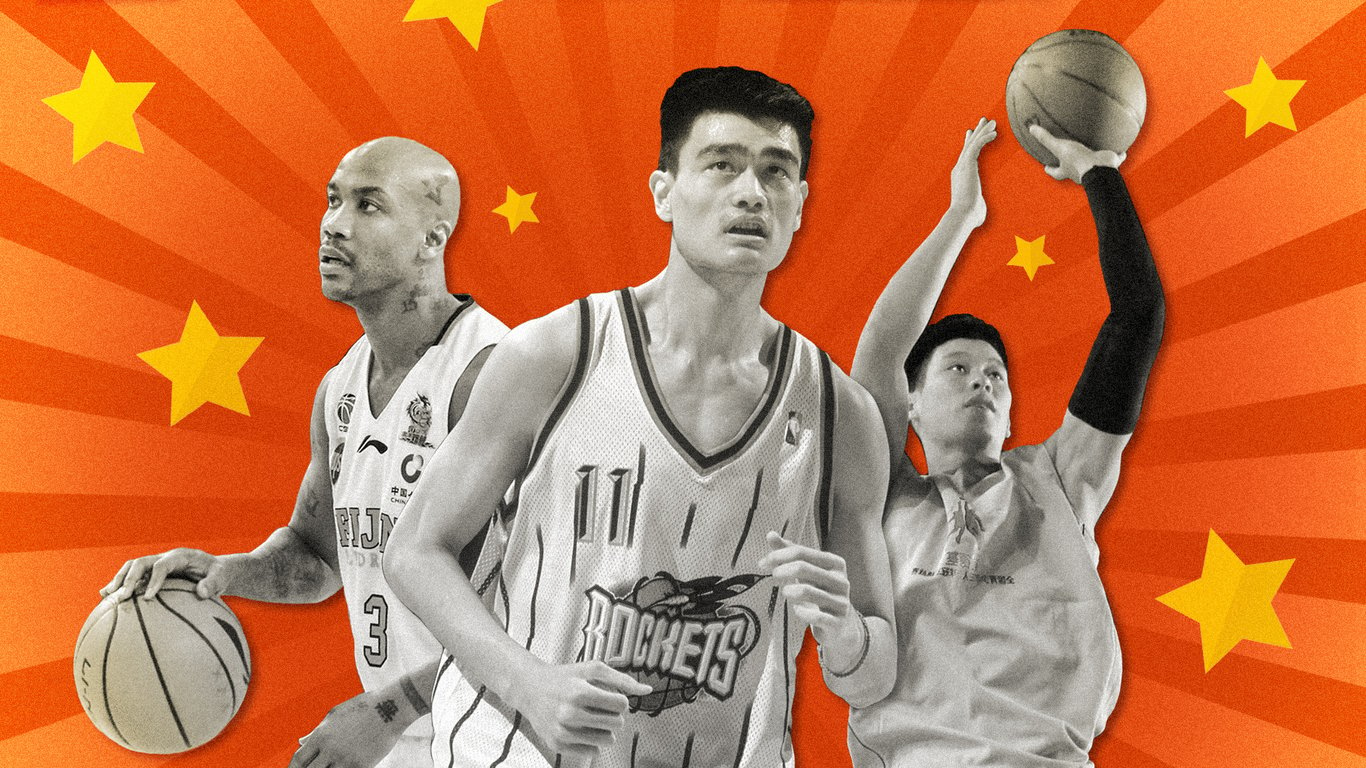

Exactly 30 years after Misaka joined the Knicks, Zheng Haixia became the first Chinese basketball player to play professionally in the U.S., signing to the Los Angeles Sparks of the WNBA in 1997. Four years later, the Mavericks picked up the first male Chinese player, Wang Zhizhi.

While Zheng and Wang played only one and four seasons, respectively, their presence paved the way for one of the biggest names — literally — in Houston Rockets basketball.

It’s hard to exaggerate how big of an impact Yao Ming had on Chinese engagement with the NBA. A number one pick by the Rockets in 2002, straight from the CBA’s Shanghai Sharks, Ming’s selection was met with a wave of booing from audiences as he celebrated alongside his family in China.

At 7-feet-6-inches tall, Ming was one of the most imposing players in the league (the second-tallest NBA player in history) and had an accomplished career with the Rockets, albeit one plagued by injuries.

Nonetheless, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2016, both for his basketball acumen (averaging 19.0 points, 9.2 rebounds, and 1.9 blocks) and for his role as an ambassador for the sport in Asia.

To date, Ming is one of only seven players from China to compete in the NBA.

Jeremy Lin Makes It Big

Lin’s ascension, from unrecruited high schooler to undrafted college grad to Golden State point guard, was indeed remarkable. But his introduction into the NBA proved challenging for the rookie.

In his inaugural game on October 29, 2010, the Warriors’ Asian Heritage Night, Lin was met with excited cheers from the home crowd every time he stepped onto the floor. He was, after all, a local kid, and in a city that is nearly 36% Asian.

He played a total of 29 games with the Warriors but struggled to wow the coaches and gradually earned fewer minutes as the season progressed. It didn’t help that he was playing with two of the league’s best guards — Stephen Curry and Monta Ellis.

Lin bounced between the G League and the Warriors bench three times in his first season, impressing the coaches enough to call him back each time. But in his final 10 Warriors games, Lin played an average of only two minutes. He was waived from the team in December 2011.

“I actually ran over to his house that day or the day after with a camera to get some raw … in the moment feelings of what he was thinking,” Yang tells RADII.

“You could tell he was shaking. He was just like, ‘I don’t know what my future holds,’ you know … ‘I don’t know if I’m gonna go play overseas, I don’t know if I should just quit basketball.’”

Lin was briefly signed to the Houston Rockets but was waived again before playing a single game. Then came the Knicks.

His career in New York didn’t provide much reassurance in the beginning. Again, he found himself in the G League. Again, he was called up. But there was a deadline coming, and both Lin and the documentary crew knew he was nearing his last shot at proving he belonged in the NBA.

“Honestly, I feel like we were sort of feeling defeated, too. Not even so much from a film standpoint, but at this point, feeling kind of bad for Jeremy, like, ‘man, I know he’s wanted this so bad and for it to end like this.’”

At this point, Yang and the crew were still figuring out how to end their film. Lin, meanwhile, uncertain about his future in New York, was sleeping on the couch of teammate Landry Fields the night before his make-or-break game.

Then came February 4.

Amid a dismal, injury-plagued season and having lost 11 of their last 13 games, coach Mike D’antoni called upon Lin, on the recommendation of Knicks legend Carmelo Anthony, in the hopes of turning around a losing match against the New Jersey Nets. Up to this point, Lin spent most of his time warming the bench.

Lin scored 25 points that game, with five rebounds, seven assists, and two steals, propelling the team to a 99-92 victory.

“I logged onto my phone, and I was like ‘holy shit, he’s going crazy right now,’” says Yang, who hadn’t been watching.

“I remember texting Evan, and everyone was caught off guard because no one was watching at the time … I remember Evan saying, ‘you know what, we have the ending for our film now.’ And I’m like, ‘yes, if nothing else happens for him after this, this is it. We have an end.’”

Of course, this was only the beginning. So began the Jeremy Lin Show.

Linsanity

The energy in New York City was palpable. The name Jeremy Lin was everywhere. The run was on. In the following game against the Utah Jazz, Lin racked up 28 points in his first career start. Losing Carmelo Anthony early in the game and without Amare Stoudemire, the team secured their second straight win.

Two days later, Lin went head to head with Washington Wizards point guard John Wall — the number one pick the year Lin went undrafted. He scored 23 points, and a career-high 10 assists, and the Knicks returned home victorious for the third game in a row.

Jeremy Lin vs. the Lakers. Image via DvYang/Flickr

It was back in New York that Lin would have his biggest test yet: A matchup against one of the NBA’s most famous players and his future teammate, the late Kobe Bryant.

Leading up to the game, Kobe famously told reporters, “I don’t even know what [Lin has] done. Like, I have no idea what you guys are talking about.”

While Lin never entertained any drama in the press, he laid it all down on home court, putting up a career-high 38 points, plus four rebounds, seven assists, and two steals.

“Jeremy Lin was the toast of the town, and we’re sitting there with the guy, pinching ourselves and going, ‘is this really happening?’” says Yang.

“I can’t even imagine what it was like in his head living it, but for us, just kind of feeling obviously proud for our friend, but knowing that this movie suddenly had a new chapter, that made it a lot more interesting to a lot of people.”

The interest didn’t stop with basketball fans. Suddenly the film industry wanted a piece of the story. People who had dismissed Yang and the documentary crew in the past now wanted to share in the spoils of their production.

“We had this big call with Paramount Pictures. They were like, ‘we recently made the documentary on Justin Bieber, and this story is bigger than that!’” Yang says with a laugh.

“Basically, you know, [they were] showing off, doing the Hollywood thing, trying to impress us as to why we should work with them,” he says, adding that they were in awe at the time. “Someone’s really telling me that this story is bigger than the Justin Bieber story? Okay.”

Lin, meanwhile, was being solicited by the Knicks’ number one fan, director Spike Lee, who also wanted to share his story on screen.

Clear photo: @JLin7 and Spike Lee. what a CUTE smile! #webbyawards @Linfields_bros @TeamLinFields pic.twitter.com/IdD2bq74

— Vianna Liu (@vianna_liu) May 22, 2012

Ultimately, though, both Lin and the documentary crew agreed to stay true to the original vision, with the same folks at the helm of production.

“We started this whole thing on a shoestring budget with nothing but an idea and some passion. Even if it doesn’t go anywhere, we’re gonna see it through. We’re gonna finish it that way,” says Yang.

The most iconic single basket of Lin’s legendary 26-game stretch came days later against the Toronto Raptors, when he sunk a game-winning three-pointer with less than a second on the clock.

The cherry on top of a 27-point night, even the crowd at Toronto’s home court went crazy. One group of Asian-Canadian fans even bulk purchased 300 tickets for the game.

As the old adage goes, all good things must come to an end: Lin’s performance helped propel a struggling Knicks franchise to the eighth seat in the Eastern Conference of the 2012 NBA playoffs, but Lin himself would not play.

He suffered a partial meniscus tear to the left knee that required surgery, and played his final game with the Knicks on March 24, 2012 — a 13-point night against the Detroit Pistons.

Media Malpractice

Lin was no stranger to brushing off racist comments on the court, but the fame ignited by Linsanity brought levels of ignorance to new heights in the media.

Of course, there were the innocuous, albeit lazy puns: ‘Lin and a prayer,’ ‘Lincredible,’ ‘Linsane,’ ‘Amasian.’ But it didn’t stop there.

ESPN Anchor Jorge Andrés once noted Lin “was cooking with some hot peanut oil,” while multiple outlets, ill-intended or not, used a common sports phrase that, in the context of an Asian player, contains an obvious racial slur.

But arguably the worst, most cringeworthy comment came from then-ESPN reporter Jason Whitlock. After Lin’s monumental performance against the Lakers, Whitlock took to Twitter with a comment that managed to be both racist and sexist: “Some lucky lady in NYC is gonna feel a couple inches of pain tonight.”

Good one, Jason.

In what might be the most predictable career trajectory ever, Whitlock has since worked his way down the journalism ladder to the quasi-journalistic, ultra-conservative outlet Blaze Media, where he hosts a rage-baiting podcast called Fearless.

Even fellow basketball players have felt the need to hurl ignorance-fueled rhetoric in Lin’s direction. Upon his return to the G League in 2021, Lin was called Coronavirus by a fellow player who he chose not to name publicly.

Meanwhile, Enes Freedom (formerly Enes Kanter) singled out Lin, who, need we remind everyone, was born in America, for playing in the CBA, simply because of his Taiwanese roots.

Shame on you @JLin7

Haven’t you had enough of that Dirty Chinese Communist Party money feeding you to stay silent?

How disgusting of you to turn your back against your country & your people.

Stand with Taiwan!

Stop bowing to money & the Dictatorship.Morals over Money brother

— Enes FREEDOM (@EnesFreedom) December 5, 2021

“How disgusting of you to turn your back against your country & your people,” caviled Freedom, while remaining silent about the two dozen and more other former NBA players currently in the Chinese league.

For a long time, Lin brushed off the comments and stayed fairly quiet about the ways his ethnicity played into how he was perceived, instead focusing on the game. That would eventually change.

Jeremy Lin After Linsanity

In the decade since Linsanity, Lin has used his voice to support the Asian community. In recent years, that has meant shedding light on the rising epidemic of hate and violence directed at Asians around the world.

Lin addressed the complexity of his role as an activist during a 2021 roundtable hosted by PaleyImpact: “I was just naive. I didn’t understand just how systemic it was, how subtle it was. And even when people would do things really overtly — whether it was tweets about penis size, like, crazy stuff, I would be like, ‘okay, he’s ignorant,’ or, ‘okay, he didn’t understand.’

“That was kind of just my way of dealing with it, because when I was dealing with racism, which happened all the time in terms of on the court, it was just like, ‘I can’t focus on that.’ Like, ‘I’ve got to be me, and I have to be as great as I can be.’”

Lin has been steadfast in his support for his community ever since, even to the detriment of his own career.

“Do I talk about this activism stuff? Because it’s seen as a distraction, and it’s like people are saying, even national reporters are saying, ‘It’s hurting Jeremy’s case for getting back into the NBA by talking about this stuff,” he says.

“One thing I’m trying to learn as I get older is I gotta be more unapologetic and just be who I need to be and say what I need to say.”

Maintaining the level of play characteristic of the Linsanity era would be next to impossible for any player in the long term.

With 480 games played in the NBA, Lin averaged 11.6 points, 2.8 rebounds, 4.3 assists, and 1.1 steals, putting him comfortably ahead of the average point guard in the 2010s, and certainly proving that he belongs in the NBA.

The top-ranked players based on their first 12 games as NBA starters. Data via The Guardian

But as Lin fought for his last shot in the league in 2021, his age, injuries, and an impossible bar that he inadvertently set for himself became barriers.

In an industry as cutthroat as professional sports, Lin’s farewell to the NBA isn’t especially unique. But his career as a whole and his journey into the league make him one of the most incredible success stories in basketball history.

For a holistic picture of just how remarkable that journey truly was, we’re lucky to have the documentary Linsanity.

“I consider myself to be very lucky. Being someone that was very passionate about Asian Americans and basketball, seeing Jeremy’s story materialize, even if I didn’t do the movie or get to know him, I would have felt so much pride and joy over the whole thing,” says Yang.

“I think that whatever success means to you, there’s a lesson there to be learned, right? That people say no, they are always doubting you, you’re constantly the underdog. You work hard, and for Jeremy there’s a lot of the element of faith to it, and good things can happen. We were able to capture that as it was happening, fortunately.”

It’s been a while since Yang and the crew have seen Lin face-to-face. He is playing ball thousands of miles away, after all. But he and Yang remain in touch, and one thing is for sure: Neither their friendship nor the Jeremy Lin story ends with the NBA.

“This being the 10-year mark of Linsanity … the Knicks even gave a nod to him on their social media. Everyone knew how big of a story it was. You could see the love and support, even from the Knicks Nation fanbase. Like, man, we miss that,” says Yang.

“That was the best time of our lives.”

You might also like:

How Basketball Became China’s Most Beloved SportAnd no, it’s not just because of Yao MingArticle Aug 28, 2019

How Basketball Became China’s Most Beloved SportAnd no, it’s not just because of Yao MingArticle Aug 28, 2019

Cover image via Depositphotos