Last week, French luxury brand Dior became the latest in a string of foreign brands to draw heavy criticism from Chinese netizens and media over their representation of Chinese culture and people.

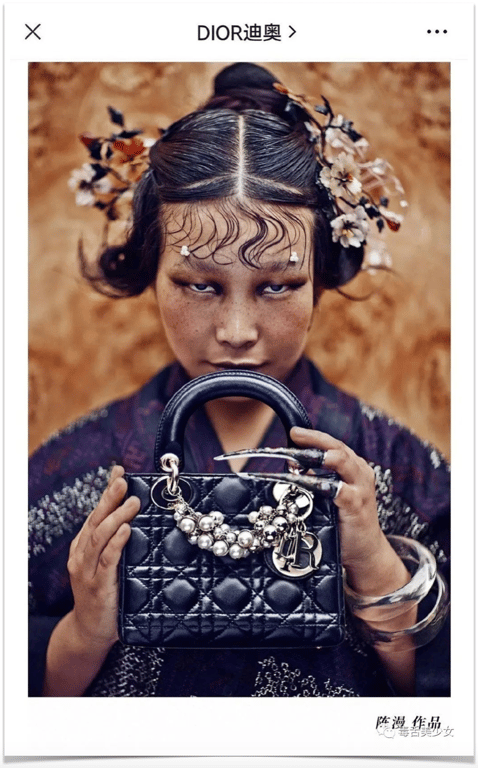

The latest controversy comes in response to a photograph of a woman wearing a traditional, Qing Dynasty-esque garment, staring hauntingly at the camera while holding a Lady Dior handbag. The ad has been accused of pandering to Western stereotypes of Chinese people.

The photograph was swiftly removed from the exhibit, which closed on November 23, and the photographer has posted an apology on the Chinese social media platform Weibo, humbly accepting netizens’ critique.

Dior has not publicly apologized for the photo. Liu Jianna at China Daily has called for an apology, and while this wouldn’t be the first time Dior has apologized, the brand has been mum on the issue.

The now infamous Lady Dior photo, by Chen Man. Image via Weibo

Anger from Chinese netizens is understandable and valid. And critics have addressed the fact that the photo is much less glamorous than other pieces in the collection.

Many expressed concern with the kind of woman featured in the image: freckled, tanned (or seemed tanned due to the lighting and angle), with smaller, monolid eyes, and less pronounced features, styled to look like she lived a couple of centuries ago. Beijing Daily paired the photo with this headline: “Is This the Asian Woman in Dior’s Eyes?”

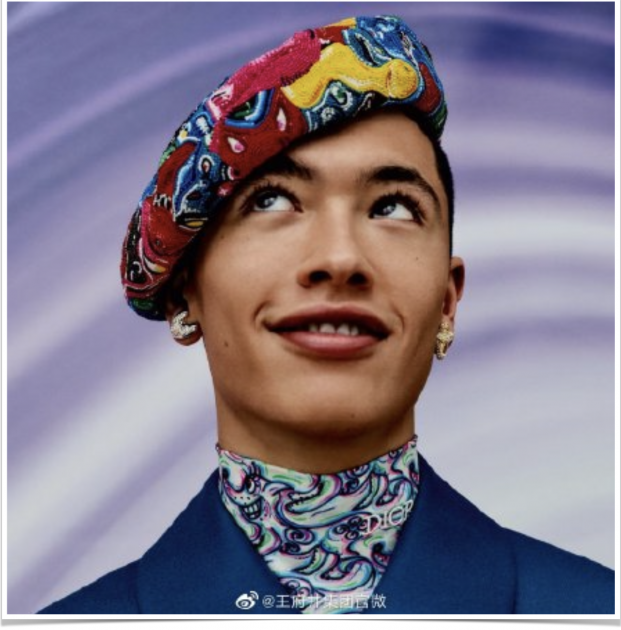

The controversy comes just months after Jing Daily lauded Dior’s Guochao menswear for avoiding “cultural cliches.”

Dior combined traditional Chinese culture with modern style in its 2021 fall menswear collection. Image via Weibo

Many commentators also took pains to pull out photos of the photographer herself. Yes, the photographer whose image caused such an uproar, Chen Man, is herself a Chinese woman.

Born in Mongolia and raised in Beijing, Chen has been lauded as a rising star and was dubbed the “Chinese Annie Leibovitz” by state-backed publication Global Times.

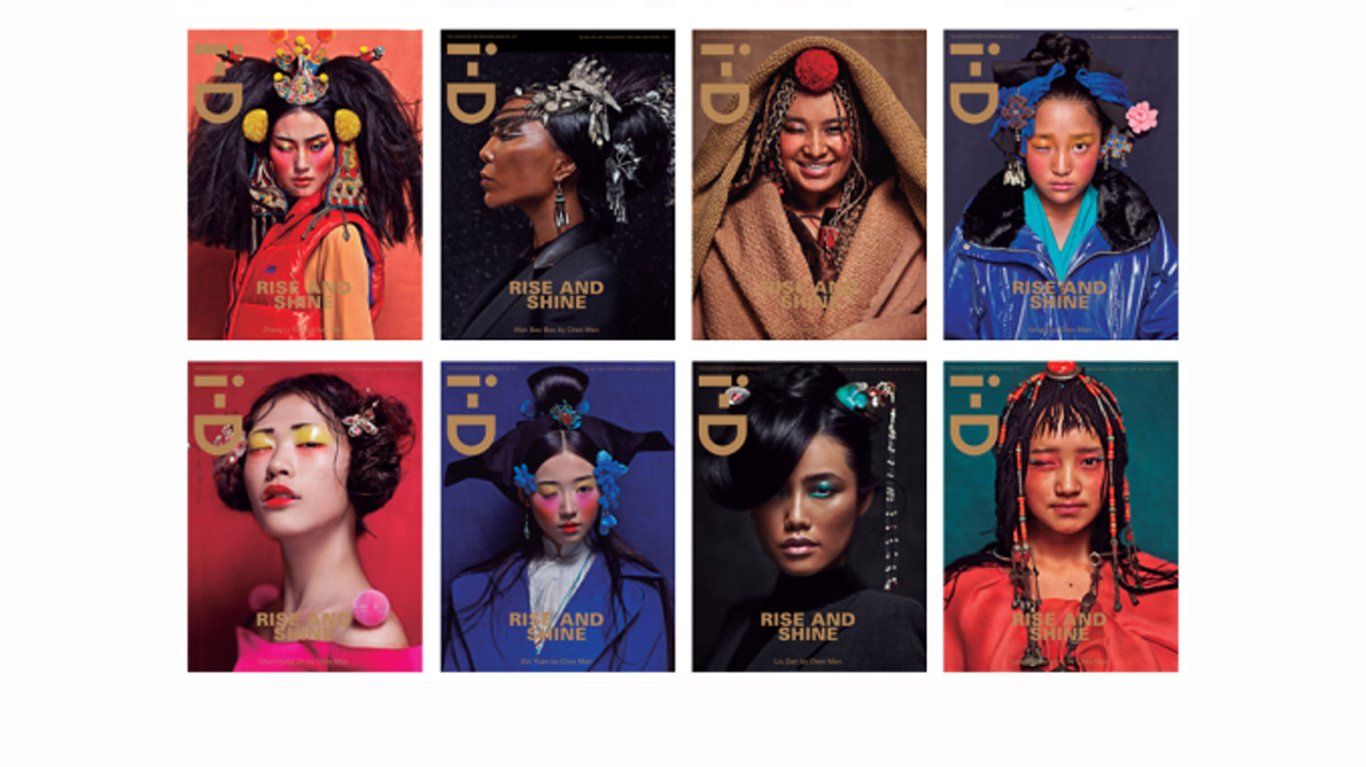

She has a stunning portfolio of work, including (but far from limited to) a collection of covers she shot for i-D magazine in 2012, featuring ethnic minority women from regions throughout China.

Many of the comments on Weibo maligned her latest work, claiming she has portraits where she looks “international and attractive,” while she “purposely made Chinese women ugly for international brands and publications.”

There are ample historical reasons for people of Chinese heritage to be sensitive to these slights. Many racial slurs specifically attack our physical attributes: slant, panface, yellow peril.

One can argue that having a strong opinion on the matter is a newly-earned privilege. Most luxury brands didn’t feature Chinese faces on their billboards and runways consistently until China started becoming one of the biggest markets for luxury goods. With purchasing power came influence, a collective voice that global brands now take seriously in matters of representation.

But there is a fine line between demanding authentic, respectful representation and bullying brands and individuals. Many of the online comments are stepping over that line.

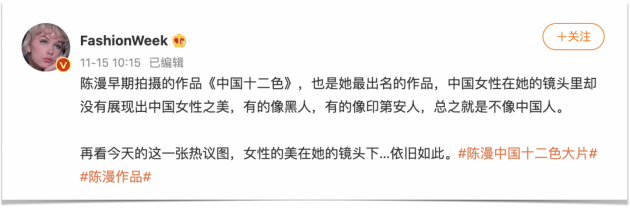

“Chen Man’s previous work titled ‘The 12 Colors of China’ is her most famous work. But she didn’t show the beauty of Chinese women through her lens. Some look Black, some look Native American, anyway, they don’t look Chinese,” wrote one fashion blogger on Weibo (screengrab below).

The long-overdue shift is undoubtedly worth celebrating. But while employing this newfound influence to demand more accurate, authentic Chinese and Asian representation in the media, we shouldn’t forget this: There isn’t one way to look Chinese.

But there is one way to be considered beautiful in China. Just ask the filters — or the plastic surgeons.

Chen Man’s i-D covers feature women from some of China’s 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities. And even amongst Han Chinese, from Mongolia to Sichuan to Hunan, there is variety in our features.

The question “what’s the average height of a Chinese person?” is moot, because depending on the region, the average Chinese male height parallels those of the average Swiss man or the average Costa Rican man. A wide range of climates and altitudes means we also sport a wide range of skin tones.

While some might argue that current Chinese beauty standards are rooted in centuries of Chinese aesthetics, they actually reflect recent trends.

Pale skin, large eyes with double folds, tall and slim nose with small nostrils, pointed chin, soft, rounded cheekbones, pouty lips — all the normative markers of so-called beauty are heavily advertised by plastic surgeons or achievable through popular photo editing apps.

Wild conjecture here, but does anyone else feel like these add up to something resembling Barbie or an anime character?

To be clear: plenty of Chinese people naturally sport these features, especially the Uighur ethnic minority.

Speaking to NPR in 2019, Urumqi-based model Xahriyar Abdukerimabliz stated confidently, “Not to brag, but we are very good-looking. Our facial features are naturally attractive. We’ve got great eyebrows, big, beautiful eyes, and double eyelids that weren’t created by a surgeon.”

Uighur model Xahriyar Abdukerimabliz. Image via Weibo

And brag he should, he’s a very handsome man. The NPR article went on to describe how, over the years, as China’s consumer market evolved, local brands no longer wanted to hire white models (to give their brands a more international, and therefore ‘high-end’ look), so they started looking for something in between. Uighur models, with their Eurasian features and Mandarin fluency, naturally snatched up plenty of jobs.

I myself had a five-year part-time modeling career in Taipei, where I was often the only Asian face in a line-up of white (English, Estonian, Brazilian, Ukrainian) models. While growing up, magazine covers and billboards mainly featured white models and celebrities, spare a few local celebrity endorsements.

Agents and clients have tried to convince me to wear colored contact lenses, or to pretend I could only speak English, to pass me off as mixed-race — for higher compensation.

Is it any wonder that we’ve internalized such a skewed standard of beauty when, for decades, we’ve seen little to no representation of ourselves in the media?

None of this is to criticize Chinese or mixed-race people, but to point out the harm in promoting a specific set of features: pale skin, larger eyes, taller nose, softer bone structure. This is what’s considered ‘beautiful’ in most of East Asia.

Actress Fan Bingbing is a good example of what is considered a ‘perfectly beautiful’ face in China. Image via Weibo

The features that have been so heavily criticized, the same that have drawn such ire from Chinese state media and netizens, have been used to deny opportunities, drive up filter and editing usage, and increase plastic surgery demand. Worst of all, they are employed to bully the women unfortunate enough to be featured in these controversies.

But all of these are Chinese features. There shouldn’t be just one way to look Chinese. So while we demand international brands to do better, let’s not demean ourselves and our own in the process.

Demand better by demanding more diversity. Instead of casting for features that conform to Western stereotypes, widen the net.

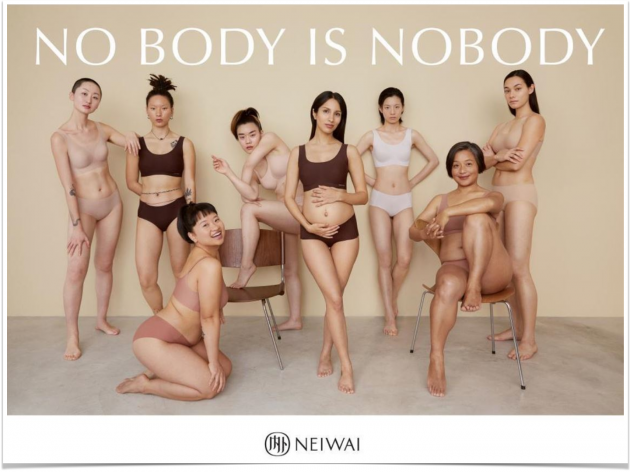

Many domestic Chinese fashion brands have already embraced these attitudes. NEIWAI is an excellent example of a brand that promotes inclusivity and female empowerment with the campaign “No Body is a Nobody.”

Chinese fashion brand NEIWAI’s ‘No Body is a Nobody’ campaign. Image via NEIWAI

If the goal is to have an authentic representation of Chinese beauty and combat international brands’ preference for hiring Chinese models of a particular look, we need to demand diversity. More Chinese women should be celebrated, not less.

Bullying Chinese women into conforming to a narrow, Eurocentric standard of beauty is like pulling them out of the frying pan and into the fire. And that’s not okay.

This article was updated at 2:55 PM on November 24, 2021, to clarify that Dior has not issued a public apology for Chen Man’s controversial photo. The brand has, however, said that it “respects the feelings of the Chinese people.”

Cover image via Weibo