Club Seen shines a light on the artists, VJs, and designers providing a visual dimension to after-hours underground culture in urban China.

Born in the barren, icy Jilin province in China’s deep northeast, Qian Geng grew up with three main sources of influence. The first was classical Chinese culture: the calligraphy brush he first picked up at the age of four would become a constant companion for the next 20 years. Blessed with parents and a public school that encouraged his nascent creative streak, Qian honed his skill by practicing with poems from Tang dynasty greats Wang Wei and Li Bai.

The second is religion, or, more broadly, folk tradition. Surrounded by belief systems ranging from mainstream Taoism to shamanistic local practices, Qian has long held an interest in the aesthetic trappings of rite and ritual.

And third: the pulpy, grimy Hong Kong horror flicks of the 1980s and ’90s, with their evocative on-screen depictions of Chinese ghosts and ghouls including the Qing-era “hopping zombie,” or jiangshi.

Related:

After trying his hand at more contemporary forms like graffiti while at university in Jilin’s capital, Changchun, Qian packed up some of his work and relocated to Beijing in 2013 to participate in a group exhibition in the 798 art district. Since then he has expanded his practice, seeking to blend the ancient craft of calligraphy with graphic design and performance, often collaborating with other left-field luminaries such as avant-garde saxophonist Wang Ziheng. Most recently he’s linked up for a collaborative live set with Taipei doom/drone duo Scattered Purgatory, with whom Qian is currently touring in Europe.

Ahead of that, I spoke with Qian — who performs and exhibits under the name The8Immortals — about his provocative performances, his heterodox combination of influences, and his philosophy of creativity, which runs toward the deep end of the Tao…

RADII: Where are you from originally? I think I read you’re from 东北 (dongbei – the northeast)? How did this environment influence you when you were young?

Qian Geng aka The8Immortals: My hometown is a small town in Jilin, northeast China. Most of the time, it’s covered with thick, white snow, and it’s desolate. This cold environment has influenced me and made me particularly fond of optimism.

How did you first become interested in making art? Did your parents support you in this, and did you have access to resources to study art in your hometown?

When I was 4 years old, my parents asked me about my interests. I first picked up a brush pen, wrote and painted, and got their support and encouragement. Because the primary school in my hometown had a special, daily calligraphy course, I was fortunate to learn calligraphy with a lot of teachers and classmates over a long period of time. This choice has let me live with calligraphy for more than 20 years now.

What were some important Chinese influences on your aesthetic when you were first starting out? Foreign influences?

Many things from traditional Chinese culture have influenced my calligraphy and artistic creation, from different perspectives: martial arts, qigong, traditional Chinese weapons, dramatic dance, religious rituals, ancient poetry, and so on. And I also have a special liking for Chinese classical wuxia [a genre of fiction depicting heroic tales of martial artists].

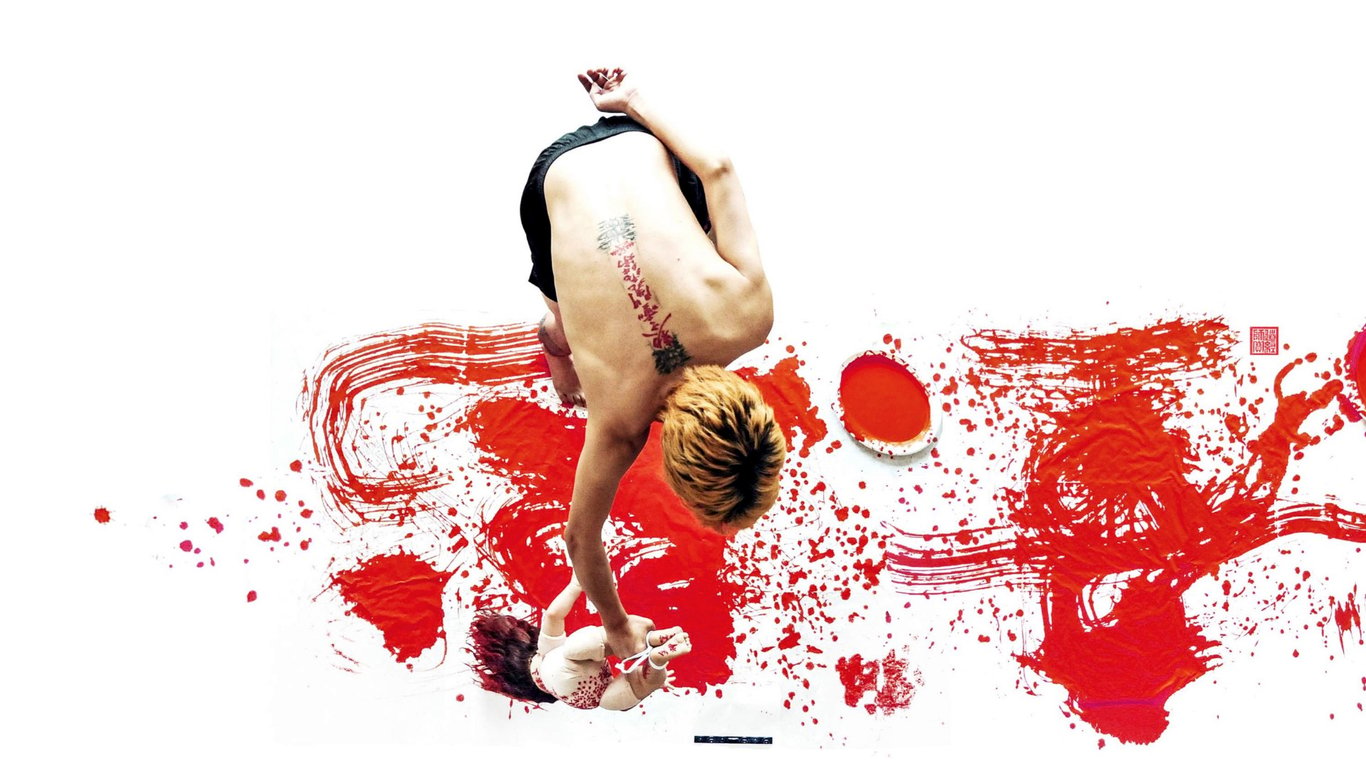

These ancient predecessors are like mountains hiding in the clouds — their partial face is enough to shine on me. The first words that I recall liking as a child were the black characters written across the yellow paper talisman attached to the faces of monsters from Hong Kong films. From the conventional and rigorous study of the calligraphy style of [Song dynasty polymath] Ouyang Xiu, to personal emotional catharsis, it really comes from my thinking about calligraphy as I see myself, about how to maintain strong feelings in an intelligent way, and write them down in my own style.

When I was in college in Changchun, I started to understand and practice street art and graffiti. Influenced by American hip hop culture, I made a series of graffiti works based on ancient Chinese poetry in an abandoned factory in Changchun. At that time I was also inspired Japanese contemporary artists like Hisashi Tenmyouya, Yayoi Kusama, and Makoto Aida.

The ancient sages are like a mountain whose peak I cannot see. Actually, I don’t want to be the diligent person who works so hard to climb the mountain to see the view from the peak. Fortunately, none of us can live the ethereal lifestyle of the ancient immortals — we want to express and create. The mountain is there, and it doesn’t move. Time is there, life is not old. You can just look up.

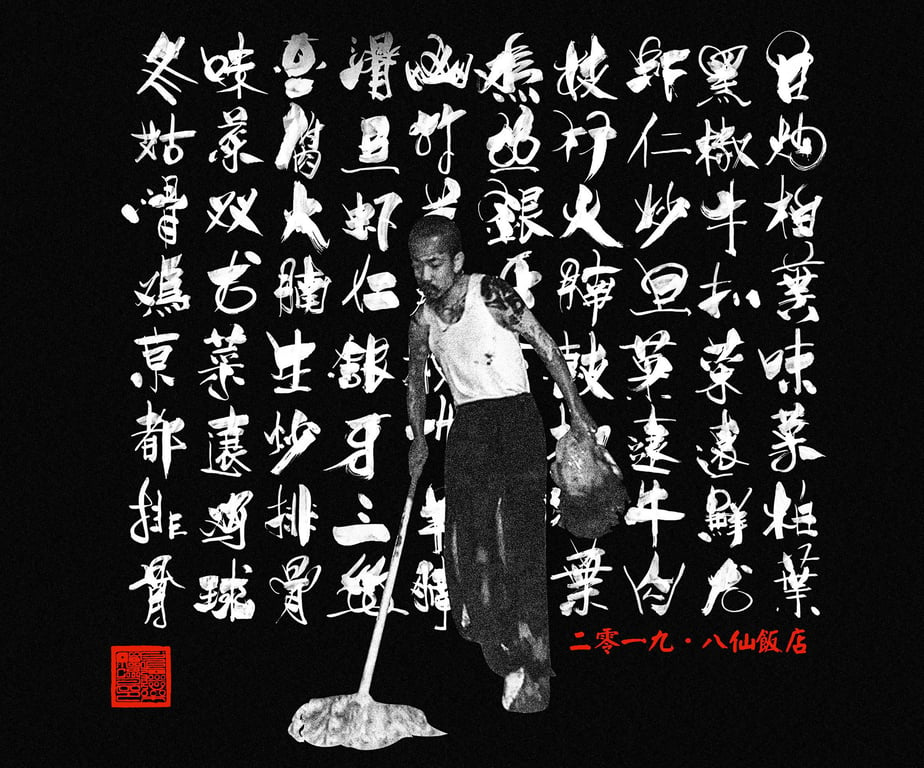

A 2019 installation by Qian Geng

When and why did you move to Beijing?

In October 2013, when was still in the third year of college. I came to Beijing with some of my paintings, because I wanted to make a joint exhibition at a gallery in 798. I had’t received any professional art training at the time. The coincidence of this opportunity helped me to treat this more casually, with the mentality of entertaining myself — for me there was no initiative to pursue systematic art training.

It seems that ancient Chinese poetry is a major influence on your work. Are there any poets, poems, or historical periods that you are especially interested in?

When I was a child, the calligraphy I wrote was mostly ancient poetry, so I recited that a lot. It also influenced me to write ancient poetry as the core expression in my current work. One of my favorite poems is Wang Wei‘s “Birdsong Brook”. My favorite poet is Li Bai. The Tang dynasty is, in my opinion, the most dreamy dynasty in Chinese history.

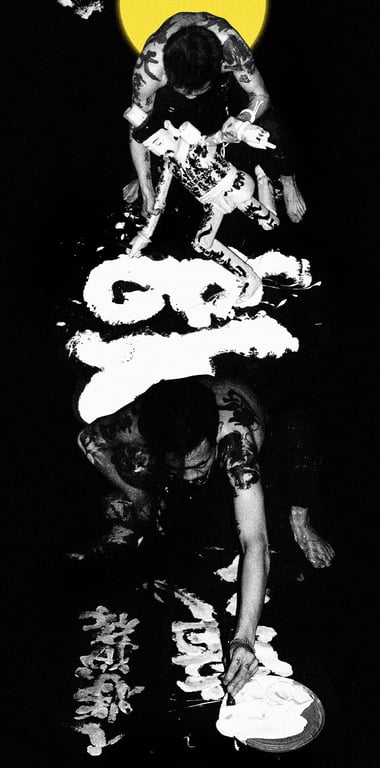

A 2019 performance by Qian Geng/The8Immortals

You also seem interested in the supernatural — ghosts, zombies, paranormal events. What interests you about these things, and how do they influence your art?

The area where I grew up is a pan-religious gathering place, religions such as Shamanism, Buddhism, and Taoism can be found there. Growing up, I was exposed to many religious rituals with folk customs that explain the supernatural. In addition, I have always liked to watch Hong Kong zombie movies, and have been obsessed with film and television dramas that combine Taoist magic, magical symbols and martial arts. It’s a pity that the decline of Hong Kong cinema has now led to an inability to see new Hong Kong horror movies, so that I cannot respond with new emotions — I need to be more self-reliant, using what I’m good at (calligraphy, performance) thing as my predecessors who filmed these zombie movies.

Can you talk about the name The8Immortals? What does it mean? What do you use this name for?

“The Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea” (八仙过海) is one of the most widely spread myths and legends in China. The eight immortals in the story represent the various classes of the ancient world: rich and poor, married and single… This is a very utopian story, full of freedom and possibility.

My project “The8Immortals” began out of my love for movies, especially the Hong Kong zombie movies I mentioned before. I was afraid of them when I was younger. But as I grew up, I found that the more mysterious figures — such as ghosts, strange things that do not exist in real life — are like fairy tales written for reality, used for peace of mind, allowing us to look at the world we have created for ourselves. Later, I slowly expanded and transformed the things I learned from the stories of these films, and turned it into the name of my work, to pay tribute.

A 2017 work by Qian Geng/the8immortals, which channels the artist’s interest in horror films

Your work blends elements of clothing design, photography, calligraphy, painting, and performance. How do you describe your own work? Which element (visual design, or performance) is more important?

The core idea of my work now is sensory integration. I think that art is the expression of personal, emotional and spiritual power. The audience and the external environment act as energy receivers. Therefore, traditional modes of expression only indirectly convey the power of the creator, because of the limitations of the carrier. So I want to weaken the last piece of calligraphy, the painting, the sculpture, an object hanging on the wall with low-frequency sounds. It is especially important to write face-to-face with others. I’m obsessed with the creation of a different dimensional space, the interaction of a huge amount of energy. The eyes, ears, and nose, five senses are emerging together.

My work besides artistic creation is graphic design, doing print titles and posters for commercial films.

I read in another interview that you take ideas from Taoist ritual into your art. How? What similarities and differences exist between religious ritual & performance art?

In my opinion, among all the elements of religion, the removal of religious nature and the return to human behavior are instinctive and creative, exactly the same as so-called art. For example, the incantations in Taoist ritual are full of design aesthetics. The paper cows and horses used in funerals in China can be regarded as art installations. The Spring Festival scrolls in the Chinese New Year are like street graffiti.

You’re about to tour with Scattered Purgatory. How do you think your visual style or philosophical interests overlap with their music?

This collaboration with Scattered Purgatory is a visually chaotic fusion of the dark state of Northern and Southern [Chinese] religions. We use our own interpretations to create a vague feeling of empty atmosphere, Qing-era zombies, Maoshan Taoism, the Eight Immortals, and the devil. The cold and sinister qualities of the visuals combined with variances in sound will create something magical.

Scattered Purgatory (photo by Professor E.)

Wang Ziheng (center)

Are there any other musicians/bands that you have worked with, or want to?

The musician that I’ve worked with the most is Wang Ziheng. In 2018, for the first annual Nowhere Festival [outside Beijing], we worked together on a performance called Wu Wo Meng Zhong (无我梦中). In 2019, we worked together to write the Dark Eight Immortals Calligraphy. Also, for the third Nowhere Festival, we produced another performance called Mountain Ghost (山鬼). We plan to tour in Germany next March, Wang Ziheng and I. There are many other musicians that I want to collaborate with — what I want most is to play with great drummers.

What are you working on now? Anything else you want to add?

At present, there are many interesting ideas that I have not yet realized, and I will get these done step by step, when the timing is right.

—

Follow Qian Geng on Instagram, and find him on a European tour with Taipei’s Scattered Purgatory through November 9.