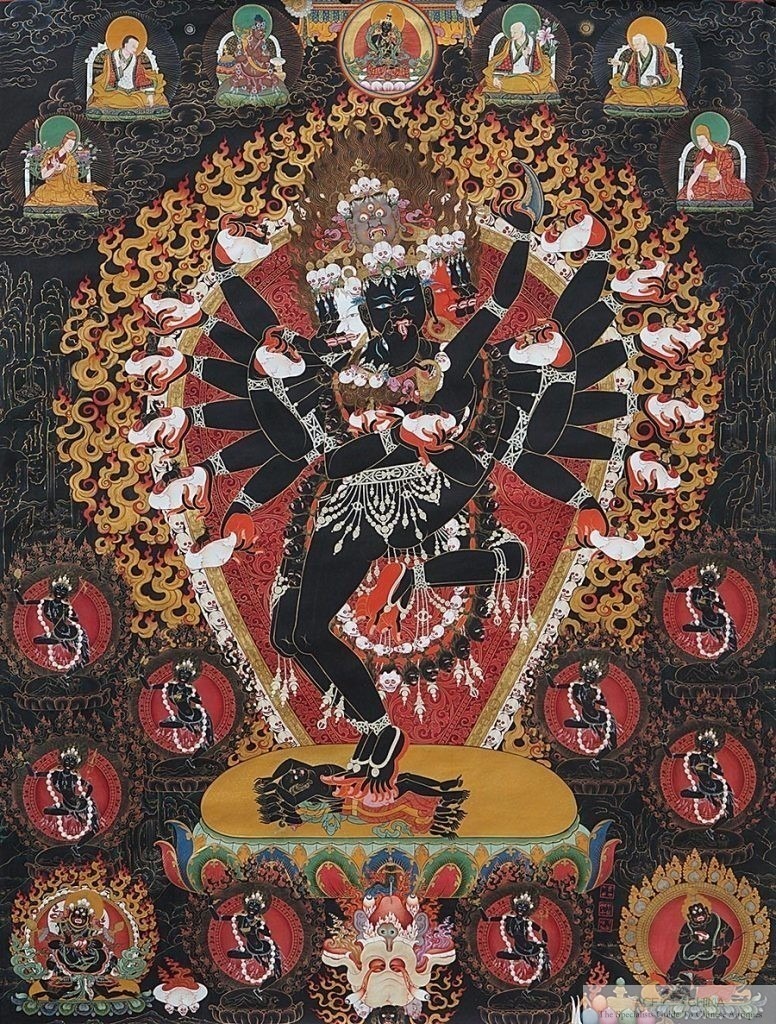

Thangka painting isn’t just another “cool spiritual aesthetic” for posters or Instagram feeds—it’s a centuries-old Tibetan Buddhist visual language grounded in precision, ritual, and spiritual knowledge. Far from freeform art, every figure’s scale, posture (asana), hand gesture (mudra), and even color palette is dictated by a rigorous system of measurements and iconographic grids designed to maintain religious and symbolic integrity.

Rooted in Himalayan Buddhism and spiritually dense visual grammar, Thangka literally means “scroll to be unrolled.” Its origins meld Indian paṭa, Nepalese brocade influences, and Chinese scroll tradition—forming a hybrid aesthetic that emerged as religious and meditative tools for monks and devotees alike.

The sacred art is methodical rather than expressive: apprentices learn grids called tik-khang for basic proportions, before layering in mineral pigments, organic saffron reds, and turquoise blues. Gold leaf adds sacred highlights, but the underlying geometry holds the metaphysical code that makes each deity both accurate and efficacious for meditation.

Though steeped in tradition, Thangka isn’t locked in the past. Across the Tibetan plateau and in diaspora communities, young painters are both preserving and reinterpreting the craft. In China’s highlands, families pass down technique through apprenticeships, while initiatives like the Tibet Thangka Art & Culture Association are exploring digital archives, academic exchanges, and public exhibits to keep the tradition alive and relevant.

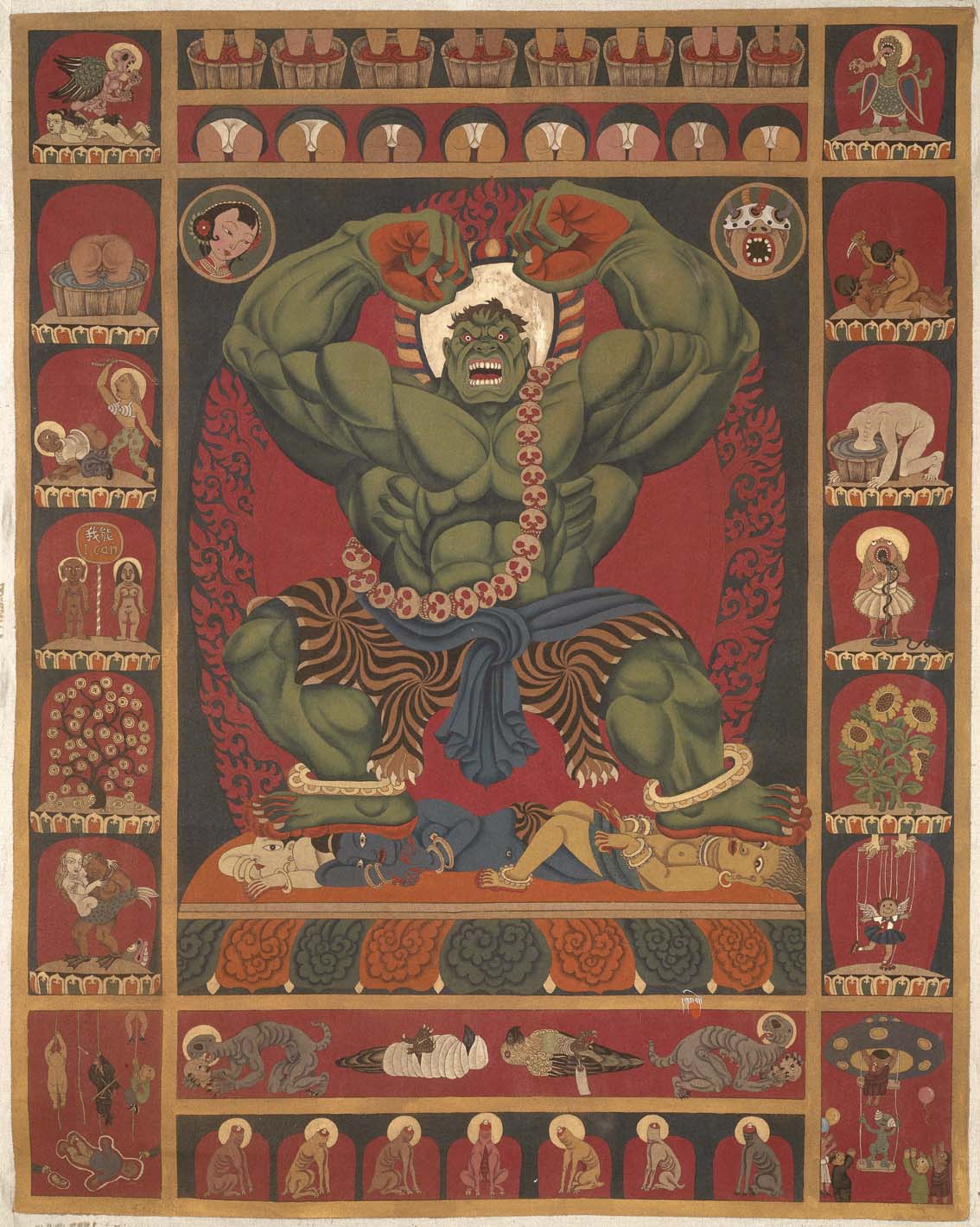

Beyond the monastery, contemporary Tibetan artists like Gade blend traditional iconography with global culture, pushing Thangka into galleries and biennales. His crossover work signals a broader trend: Thangka’s sacred structure provides a framework for hybrid cultural production—a space where diaspora identity, spirituality, and visual experimentation intersect.

Younger Thangka practitioners in places like Lhasa and Qinghai are increasingly visible on social feeds and at festivals, translating their painstaking craft into conversations about heritage, identity, and spiritual presence in a digital world. As global audiences seek depth over surface, Thangka’s blend of precise lineage and contemplative symbolism makes it one well worth paying attention to—perhaps as much attention as the Buddhist artists are paying while creating Thangka pieces in the video below.

Cover image of Detail of Vajrabhairava, Tibet (1740) via Christie’s.