For two weeks in October, a theater and exhibition space just blocks from New York City’s Chinatown became an unlikely site for Chinese feminist activism.

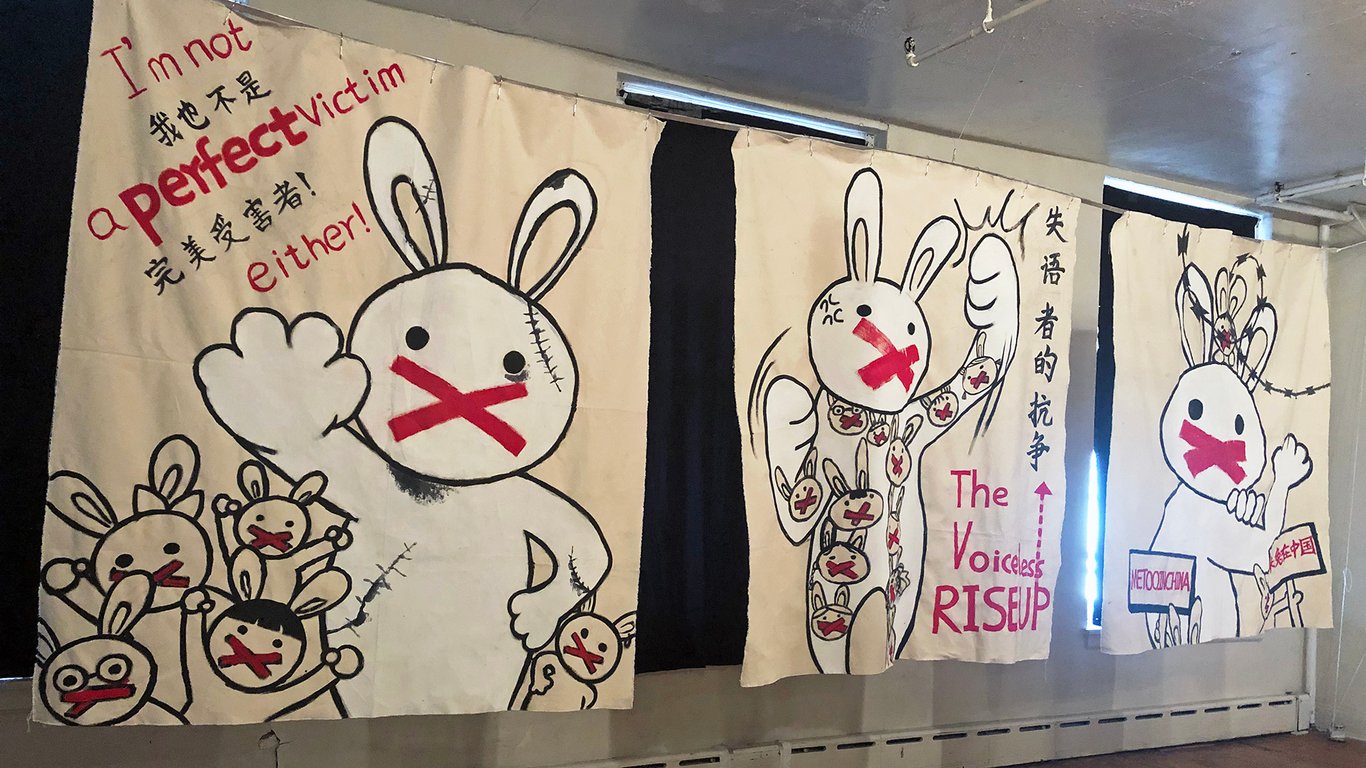

The exhibition “#MeToo in China” — which closed this past Sunday — was intended as both a review of activism against sexual harassment in China and a discussion of how to move feminism in China forward, now that discussions around sexual harassment are subject to tighter restrictions. Organized by a group of Chinese feminist activists based in New York, the show was based on an original concept created by activists back in China.

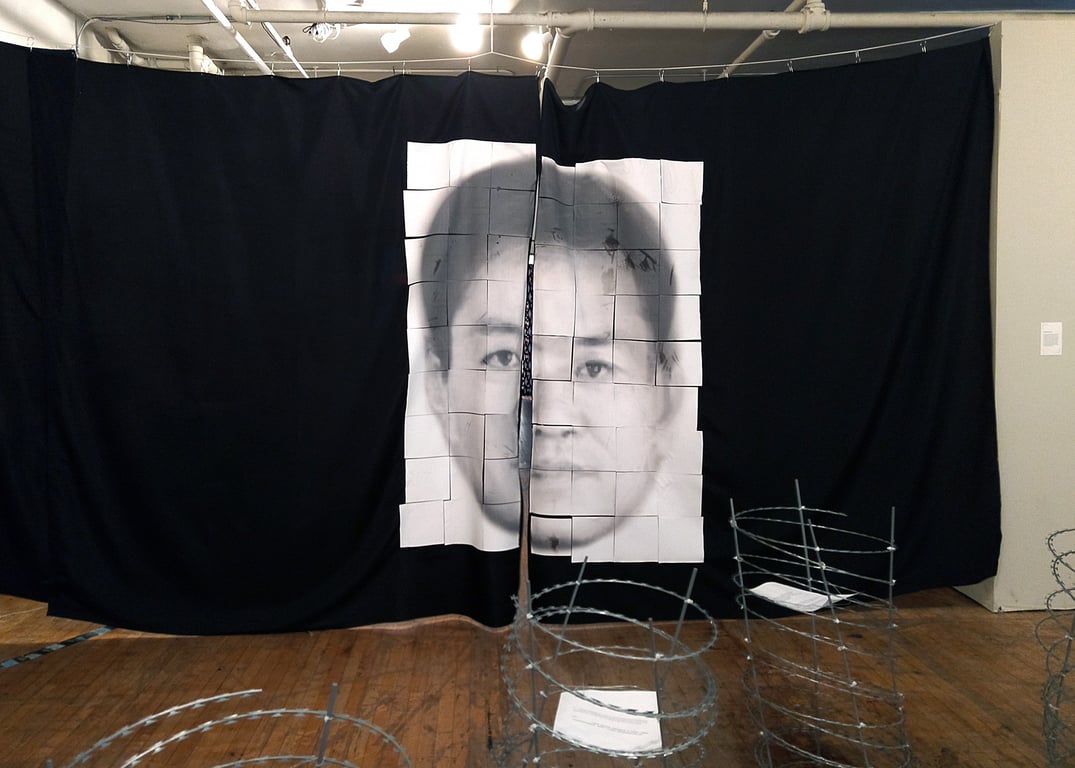

Throughout the exhibition period, a chorus of murmurs echoed through the open door, as if the space was filled with visitors in perpetual dialogue with one another. But inside, one was more likely to find the voices issuing from small speakers placed on the floor under waist-high towers of barbed wire, playing back firsthand audio testimonials of survivors describing their harrowing experiences of sexual assault in Mandarin.

Luo Mai, an activist and co-organizer based in Guangzhou, says that last year saw “several high-points for the #MeToo movement in China,” with surges in high-profile discussion both online and in media throughout January and July. “But now, online discussions are immediately censored,” she adds. “We thought it might be the right time for an exhibition to remind people that the Chinese #MeToo movement is still around.”

Inside the New York City exhibition (photo: Mimi)

The original exhibition was organized by activists in Beijing, Chengdu and Guangzhou, but stayed largely under the radar out of necessity. Local organizers disseminated information about its time and place via private networks shortly before opening to avoid being shut down. And indeed, while the Beijing iteration was designed to only run for one day, both Chengdu and Guangzhou exhibitions were quickly shut down by local authorities.

The exhibition’s fate in China is evidence of a broader trend: that feminist issues are increasingly subject to scrutiny since the arrest of the “Feminist Five” — a name for China’s most high-profile activists — in 2015. This was not always the case; “Feminist Five” activist Wu Rongrong told Inkstone that in the late ’00s, even small-scale protests and public interventions were allowed when she was actively working in Beijing. And while discussions of sexual harassment were taking place openly — even in mainstream media — for parts of 2018, the topic quickly became sensitive after several major hashtags were censored on social media platform Weibo.

Related:

Suppression, Perseverance and Anger: #MeToo in China Gains Momentum Against the OddsArticle Jul 30, 2018

Suppression, Perseverance and Anger: #MeToo in China Gains Momentum Against the OddsArticle Jul 30, 2018

This clampdown on public spaces has left feminist activists looking for new ways of raising awareness about sexual harassment — the exhibition was one of their answers. “Even though the [Chinese] exhibition was shut down, it brought people together. People even came from other provinces,” says Luo. “And it started further discussion about sexual harassment. [To us] that counts as a success.”

Photo: Mimi

Another way Chinese feminists have adapted to increasing pressures at home: take the movement abroad, to major cities like New York that have a substantial Chinese community and audience, and don’t have the fear of crackdown or censorship.

Related:

China Designers: Why This NYC-Based Label Uses Fashion to Promote Social ChangeViewing fashion as a platform for discussion, these two Chinese designers tackle a new social issue with each collectionArticle Sep 24, 2019

China Designers: Why This NYC-Based Label Uses Fashion to Promote Social ChangeViewing fashion as a platform for discussion, these two Chinese designers tackle a new social issue with each collectionArticle Sep 24, 2019

Mimi — a young professional from Chengdu and co-organizer of the New York exhibition — is part of a loose circle of activists that wanted to organize a “very DIY” exhibition that centered on Chinese feminism. She and co-organizer Liang Xiaowen had briefly considered recounting the history of the Chinese feminist movement more broadly, but settled on recreating the #MeToo exhibition that had been censored in China. “With the case of Liu Qiangdong, there was a clear link between #MeToo [in China] and the Chinese community in the United States,” she explains.

Liu Qiangdong (also known as Richard Liu) — CEO of Chinese ecommerce giant JD.com — was arrested on accusations of having sexually assaulted a Chinese student in Minneapolis in August 2018. After prosecutors eventually declined to press charges, the student, Liu Jingyao, pursued civil charges against him in May but was subject to online smears, prompting a viral support campaign on Chinese social media with the hashtag, “I am not a perfect victim either.”

Related:

JD.com Billionaire Richard Liu’s Arrest is Forcing China to Have New ConversationsArticle Sep 06, 2018

JD.com Billionaire Richard Liu’s Arrest is Forcing China to Have New ConversationsArticle Sep 06, 2018

The case was featured prominently in the New York exhibition, which included the campaigns and activities supporting Liu Jingyao as part of a timeline of Chinese activism against sexual harassment.

An installation featuring JD.com CEO Liu Qiangdong

Liu Jingyao’s case is also evidence of the entanglement between Chinese feminist communities abroad and back home. As the exhibition that took place in New York exclusively dealt with the #MeToo movement in China, it primarily drew Chinese visitors, many of whom were students like Liu Jingyao herself.

Mimi hopes that the discussion can win over some of their visitors to the feminist cause and build a community both in New York and — once people return home — in China. The term “feminism” has become increasingly sensitive and, according to Mimi, is often reduced to “hatred of men” in Chinese media, which makes it a toxic label to identify with. At the same time, censorship makes it hard for Chinese feminists to explain what they really stand for.

Mimi finds that most young women are open to feminist ideas after having discussed them aloud with her or other volunteers. “By the time Chinese women come to the United States,” she remarks, “most of them have experienced some kind of gender-based discrimination at school or in the workplace, and have an intuitive understanding of [this kind of] inequality.”

Related:

Lipstick Messages, Bunny Massages, and Marathon Manicures: Sexist Stereotypes Hit Chinese HeadlinesArticle Nov 05, 2018

Lipstick Messages, Bunny Massages, and Marathon Manicures: Sexist Stereotypes Hit Chinese HeadlinesArticle Nov 05, 2018

Luo, who continues her activism work in Guangzhou, considers the exhibition an “exercise in activism” for every visitor. She clarifies this by saying that rather than discussing feminism in theory, it confronts them with vivid, firsthand accounts of what survivors of sexual assault have gone through.

These testimonials are framed by records of the tireless activism taking place in China over the years. Like the exhibition itself, they communicate to Chinese visitors and to friends back home — who might encounter photos or write-ups in private social media networks — that they are not alone.

All photos unless otherwise stated: Quinn Yeung