In September, the National Museum of China on Tiananmen Square closed “for renovations.” This isn’t that unusual. Due to disagreements about what should and shouldn’t be included in the exhibits, the museum and its predecessors have been closed almost as often as not since the building opened in 1961.

Last week, the museum re-opened its doors to great fanfare as the enormous lobby and main galleries were transformed into a glittering celebration of the 40th Anniversary of the Reform and Opening Era.

Or at least that’s what was promised in the banners on the museum’s steps. Once inside, it was immediately apparent that this was all about one man: Xi Jinping. Everywhere you look, Xi’s smiling face and benevolent paunch stare down from videos and photos.

Deng Xiaoping (you may know him as “the guy most responsible for kicking off the Reform and Opening Era and keeping it going”) gets shunted to a corner display. Xi’s predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao also have their respective nooks, but as the giant jumbotron and center stage exhibit make painfully clear: This is a total Xi Show.

Essentially, feckless sycophants have taken the Reform and Opening period, one of the most significant moments in Modern Chinese history, and turned it into the equivalent of a Xi Jinping dick pic.

Not that you can blame the guy. The museum’s flagship modern Chinese history exhibit, the Road to Rejuvenation (复兴之路) hasn’t been updated since the last time the museum re-opened after extended renovations (read: revisions) in 2013. In its current incarnation, the Road to Rejuvenation ends with an extended meditation on the Hu Jintao era complete with a display case featuring every mobile phone I have ever owned in China.

Xi Jinping appears in the R2R only as part of the Standing Committee under Hu Jintao, just another dude with a bad dye job and an ill-fitting suit. Given what we know about Xi’s messianic complex, it’s almost incredible that it’s taken until now for him to set the record straight.

At root, it’s about narrative. Since the 1990s, the story of modern China according to the CCP has been a quasi-religious parable about a glorious civilization which existed for 5,000 years and then tragically suffered a fall from grace at the hands of evil and aggressive foreign powers, traitorous Chinese collaborators, and Manchu Quislings who gave away the nation’s sovereignty. This led to a Century of Humiliation in which many tried to save China. People with names like Hong Xiuquan or Kang Youwei or Sun Yat-sen gave it their best, but none were able to truly redeem the nation. In this version of the narrative, Sun Yat-sen at least is elevated to a kind of “John the Baptist” pointing the way forward to the real revolution and the only man – and Party – who could save China: Mao Zedong and the CCP.

What’s interesting is how that narrative has shifted in the Xi Jinping era. Now it’s Mao who is relegated to the “John the Baptist” role (to take this particular religious metaphor and beat it into the ground) preparing the way for the Great Rejuvenator, Papa Xi:

Within a month of becoming China’s leader in 2012, Xi specified deadlines for meeting each of his “Two Centennial Goals.” First, China will build a “moderately prosperous society” by doubling its 2010 per capita GDP to $10,000 by 2021, when it celebrates the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party. Second, it will become a “fully developed, rich, and powerful” nation by the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic in 2049. If China reaches the first goal— which it is on course to do—the IMF estimates that its economy will be 40 percent larger than that of the U.S. (measured in terms of purchasing power parity). If China meets the second target by 2049, its economy will be triple America’s.

So it makes sense, given this kind of grandiosity and narcissism, that Xi would want to make the last forty or so years of Chinese history into a teleological fairy tale about himself.

The thing is: The Reform and Opening era is a great story, one which goes way beyond Xi Jinping. Whether we credit the Party for creating the conditions necessary for prosperity and economic development or just thank them for taking their boots off of the necks of the Chinese people and letting them get to the job of building their own country, the last four decades have seen one of the most remarkable social and economic transformations in history. According to the World Bank:

Since initiating market reforms in 1978, China has shifted from a centrally-planned to a more market-based economy and has experienced rapid economic and social development. GDP growth has averaged nearly 10 percent a year—the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history—and has lifted more than 800 million people out of poverty.

600 million? 700 million? 800 million? I know people quibble about the numbers, but wherever you land in that range, it’s pretty impressive. And to be fair, the exhibit celebrates these changes with endless images and videos of new cities rising, trains speeding past, infrastructure, technology, science, and all the other fruits of the Reform and Opening Era. Is it a hilariously sanitized version of history? Absolutely, but it’s still a remarkable story.

But Xi Jinping didn’t have that much to do with it (although he’s doing his damnedest to write his daddy into the story) and certainly not to the extent that he deserves 75% of the floor space of an exhibit on the Reform and Opening era while Messrs. Deng, Hu, and Jiang are relegated to backup singer status.

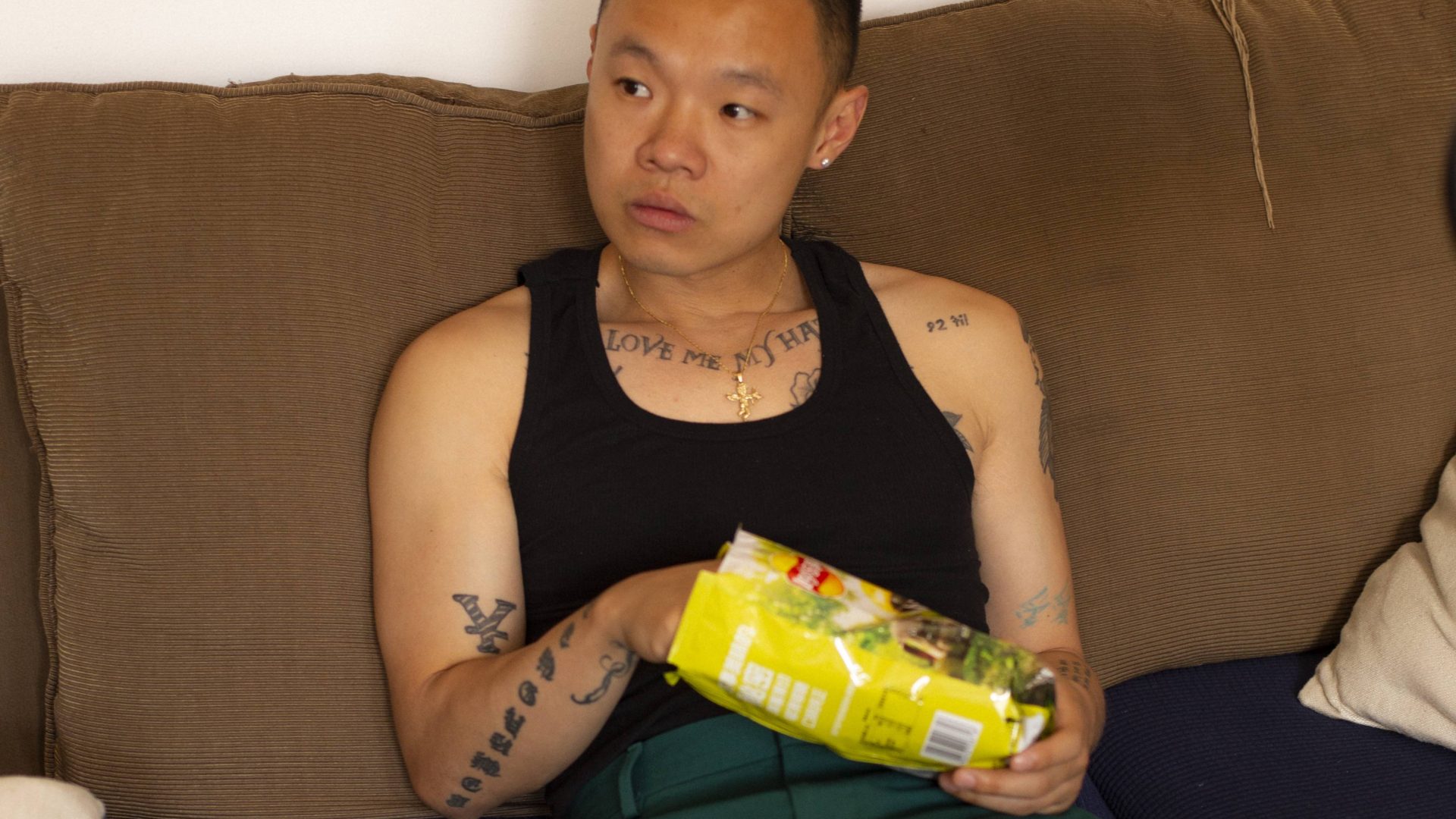

And the images aren’t subtle.

Here’s Hu in a military parade.

The expression on his face: Am I wearing pants? Did I remember pants?

Here’s Jiang in a military parade.

The expression on his face: Not only am I not wearing pants; there’s a 98% chance that a certain famous folk singer is pleasuring me at this very moment.

Here’s Xi Jinping.

See what I mean? The other two look like guests at their own parade; Xi is dressed as a field commander. Hard to miss the subtext here.

Xi as army man is an oddly consistent theme at the exhibit. For example, this photo almost got me thrown out of the museum.

I saw a woman posing her young son in front of Military Fatigue Xi Jinping. “Wow!” I said, “Is that a picture of North Korea’s Kim Il Sung?”

She looked at me as if she wanted to force choke me. It was clear she found my lack of faith in the Party disturbing. Instead, she gave that reptilian hiss that some people do when they are beyond disgust and entirely at a loss for words, grabbed her kid and walked off in the other direction. I hustled over to the other exhibit room just in case she was looking for a security guard.

Reform and Opening is one of the major events of the 20th-century world history. Philip Pan has a great piece in The New York Times entitled “The Land that Failed to Fail.” I just assigned it to my students. You should go read it. Like, now. It’s okay, I’ll wait…

I think Pan’s take is good. I’d like to see how China handles a protracted economic slowdown or recession before I call time of death on Liberalism or make any bold predictions about China in 2049, but it’s hard to argue with the last four decades. Even in the short (15 years or so) time that I’ve been based in Beijing, the changes in people’s lives over that period have been nothing short of remarkable. I know it looks different down in the village or if you’re living out in Tibet or Xinjiang, but the Party’s appropriation of Ronald Reagan’s mantra (“Are you better off now than you were four years ago?”) seems to be key to their resiliency.

As I said, this is an important story in world history but reducing it to a backdrop for a leader’s ego is… telling. I assume that once the temporary exhibit is over, many of the photos and other Xi paraphernalia will be moved upstairs to revamp the “Road to Rejuvenation” exhibit and make it suitably Xi-worthy.

It’s one thing to witness historical changes; it’s quite another to witness a group trying to change history.