What happens when an entire generation in a country of 1.4 billion people grows up on social media?

This question is central to director Hao Wu’s new documentary, People’s Republic of Desire, which recently premiered at US film festival South by Southwest (SXSW) to positive, if “disquieting,” reviews.

Wu has an unlikely background for a documentary filmmaker. Originally from Sichuan province in China’s southwest, he moved to the US for graduate school, and parlayed a background in molecular biology into an early career working for some of the world’s biggest tech firms, including Alibaba and Yahoo’s China office. Storytelling was an earlier love, however: Wu says that he wrote and directed stage plays in high school, and dabbled in screenwriting in the early aughts.

Wu’s “desire to express” stuck with him throughout his tech career, and in 2012 he moved to New York and turned his passion for storytelling into a full-time vocation.

People’s Republic of Desire, which premiered in March and won the Grand Jury Award at SXSW, follows two professional livestreamers: individuals whose sole source of income comes in the form of tips from fans who watch their broadcasts on one of China’s many livestreaming platforms. The film explores timely themes such as the extreme atomization caused by digital culture, the unique forms of desire produced by constant connectivity, and the social interactions between China’s tuhao (“nouveau riche”), diaosi (“losers”), and general internet population that are facilitated by livestreaming.

People’s Republic of Desire is currently making the international festival rounds, and Wu and his team are “getting all the distribution pieces together” for a wider release in both the US and China, as well as an ultimate online release. In the mean time, I caught up with Wu to talk about his new film and what it tells us about internet culture in China today.

[Editor’s note: livestreaming is called zhibo in Chinese, and the two terms are used interchangeably below. Find a general primer on the zhibo phenomenon here.]

RADII: Your second documentary, The Road to Fame, followed five students at a drama academy in Beijing, and explored how they had to strike a balance between intense competition in their field, familial pressure, and “China’s corrupt entertainment industry,” in your words. It’s only been five years since then, but do you think that the rapid growth of China’s entertainment and media environment, where acting, dance, and singing talent shows are now ubiquitous, has changed this equation at all?

Hao Wu: I’ve been away from that world for a while, now that I’m living in the US, but I don’t think that the “showbiz” reality in China has changed at all. If anything, it has become more intense as more money is rushing in to ride the entertainment boom. Granted — the competition and the corruption are not unique to China. For example, the US is having a belated awakening with the #MeToo movement right now, which started in its film industry. It’s just that in China, many aspects of a capitalist and consumerist society are supercharged, more extreme.

[pull_quote id=”1″]

Your new film is about the rather staggering emergence of — and the culture that’s been created around — zhibo, or livestreaming. As far as I know, livestreaming first caught on in other places — such as online gaming communities in the US and certain internet communities in Japan — but it’s a different beast in China, in my opinion. What do you think are the distinguishing characteristics of “zhibo“, ie, livestreaming specifically as it’s being done in China today?

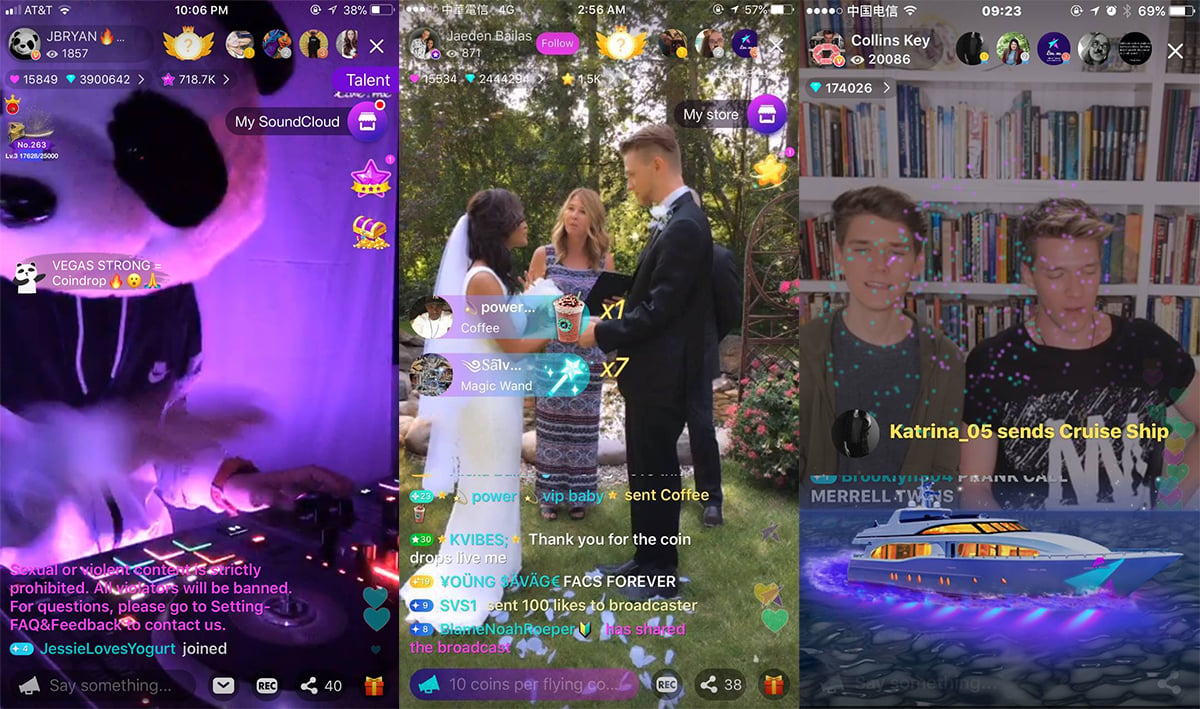

Livestreaming in China is much more blatantly about money. The relationship between fans and the livestreamers they worship revolves almost exclusively around tipping with digital gifts, which are bought with real money. In contrast, on Twitch, the largest gaming livestreaming platform in the US, livestreamers receive only a small percentage of their income from tipping.

Big Li, popular talk show host (photo by Sun Junbin)

Livestreaming has evolved in China this way because the various platforms are very good at understanding their users’ needs, and they have built a money-based ecosystem to satiate those desires unmet in real life: the livestreamers, most of them without a good education or job prospects, wanting an easy way to make a lot of money; the rich tuhao [土豪; internet slang term meaning “nouveau riche”] patrons eager to attract the attention of livestreamers, to befriend or date online celebrities, to show off their wealth; the poor diaosi [屌丝; internet slang term meaning “loser”] fans wishing to connect online after a dreary day at work, to worship their idols while consuming cheap entertainment, to marvel at the rich patrons whose spending a night may exceed their monthly or annual income.

As I understand it you are in particular concerned in People’s Republic of Desire with determining what detrimental effects constant connectivity and social media use are having on young people in China today. What were your findings here?

The internet giveth, and the internet taketh away. I don’t think the detrimental effects of technology are unique to China, though. As has been increasingly discussed worldwide, constant connectivity can be very addictive. Online connection can appear easy to cultivate and maintain, but it can readily suck you in, isolate you from real-life troubles but also real human connection and comfort.

[pull_quote id=”2″]

Right — one need only look up the latest Mark Zuckerberg news to catch a whiff of how divisive social media has become in American society. Besides obvious major differences — like what gets censored, and how close these internet companies are to their host government — what do you think are the major differences in how social media is used in China vs the US?

The social media use in each country reflects the reality, the user needs, in the respective society. In many aspects, these needs are not that different across these two countries — to express, to connect, to be recognized. But I think that, in China, due to existence of a large population of youths, especially youths who feel lonely, who feel their aspirations are being stifled in real life, the dependency of the young on social media may be higher. Consequently, the evolution and innovation in social media is on a hyper drive, much more so than in the US.

The Virtual World (Eric Jordan)

I find it interesting that the protagonists of your documentary are people who are already filming and broadcasting themselves, presumably almost daily, and for an income. What was the dynamic like when you were filming your subjects? Would they shed their zhibo persona as they turned from their phone or computer camera, and become their “real” selves when they faced your camera?

The two hosts featured in the film livestream full time. It is their sole income source. It’s actually quite boring following them day in and day out. They get up late — never before noon — and other than eating meals, sometimes with their families, they are either online livestreaming or on their phones chatting with patrons and fans to maintain relationships. I’d wait for a long time for something to happen. And by the time something happens, my characters have forgotten the existence of the camera. That’s the trick all documentary filmmakers use to let their subjects be themselves in front of the camera — time and patience.

[pull_quote id=”3″]

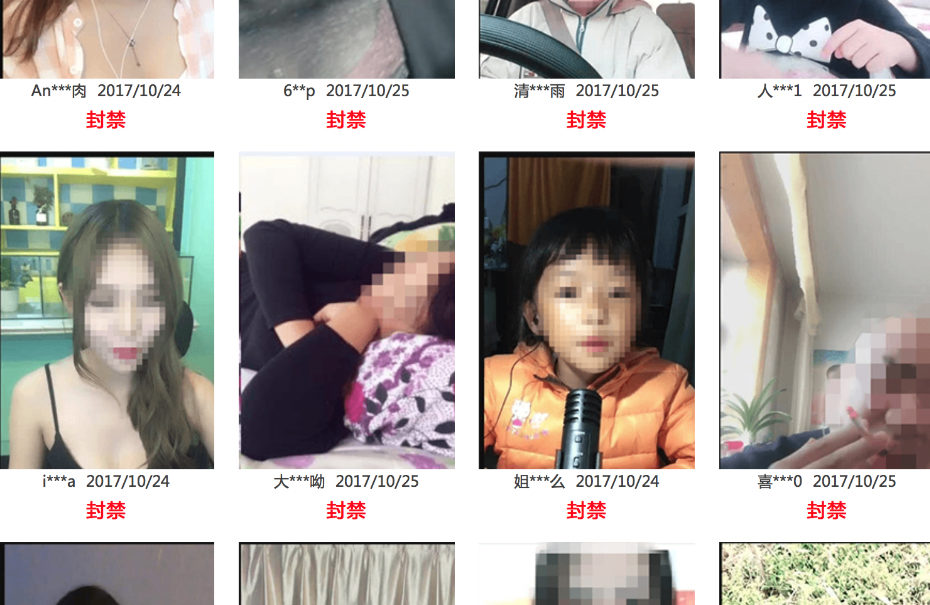

Your documentary is coming out at a moment when Beijing has just begun a focused crackdown on online video platforms, including one of the most popular zhibo apps, Kuaishou. Do you find this surprising, or did you feel something like this was inevitable as you were making the film?

The crackdown has been going on for a while. Sometimes it’s more stringent. Then it may loosen a bit before tightening again. It has picked up recently, I think, mostly because livestreaming has finally become mainstream. It’s not surprising that the government is scrutinizing this industry more and more, as there indeed exist many problems in zhibo content.

Did you learn anything interesting or unexpected about contemporary class divides or rural/urban divides in China during the course of making this film?

The most surprising aspect of making this film is the opportunity for me to truly understand the diaosi at the bottom of Chinese society. I’d only read about them before. But meeting them in real life and following them to work, to their dark dorm rooms, and to the smokey internet cafes, they frequent made me truly understand how hopeless they feel about the future. It is heartbreaking, because they are still so young.

Xiao Yong, typical diaosi fan (photo by Hao Wu)

Are there any upsides to this extremely online culture that zhibo reflects? I get a distinctly dystopian vibe from the descriptions and reviews I’ve seen of the film — including at least one Black Mirror comparison — but did you see anything positive, inspiring, or hopeful in the three subjects you chose to film?

Without livestreaming, the lonely diaosi fans may be even lonelier, their lives even blander, in real life. Without livestreaming, those livestreamers who came from a diaosi background may not be able to strike it rich, ever, in today’s China, and drastically change the life of the entire extended families. So it’s not all negative.

Finally, I want to ask about your choice of the word “desire” in the film’s title. Are you referring to the desire of fans for wanghong [网红, internet celebrities], the desire of aspiring zhibo stars to become famous, or both? What is the ultimate object of desire in the universe of zhibo?

I used the word “desire” because the online livestreaming universe, with all its intricate business logic and product features, is a reflection of all its participants’ desires — love, sex, money worship, idol worship, wealth worship, etc. Real human beings project their various desires online and power this livestreaming phenomenon in China. So there’s no single ultimate object of desire.

—

Cover image: Popular singer Shen Man (photo by Cheng Jingyang). All photos courtesy Hao Wu.

You might also like:

Will Live.me Bring China-Style Live-Streaming to the US?Article Oct 31, 2017

Will Live.me Bring China-Style Live-Streaming to the US?Article Oct 31, 2017

3 Chinese Filmmakers Making the International Festival RoundsArticle May 03, 2018

3 Chinese Filmmakers Making the International Festival RoundsArticle May 03, 2018

Zhibo: Welcome to the Weird, Wonderful World of Chinese Live StreamingArticle Jun 16, 2017

Zhibo: Welcome to the Weird, Wonderful World of Chinese Live StreamingArticle Jun 16, 2017

Apps Removed, Teen Livestreamers Banned in Latest Push to Filter “Vulgar” ContentArticle Apr 09, 2018

Apps Removed, Teen Livestreamers Banned in Latest Push to Filter “Vulgar” ContentArticle Apr 09, 2018