This article is co-authored by Biyi Feng and Yan Zhou, founders of the website Elephant Room. It has been re-published here with their permission.

Yan and I were reading the recent Facebook scandal and the consequent #deletefacebook movement, and suddenly, our thoughts went wild:

It’s hardly news that WeChat, China’s biggest social app, is invading our privacy too. Will there ever be a #deletewechat movement in China? And if so, would we join it?

“No, no way.” – Me.

“Me neither. Just NO.” – Yan.

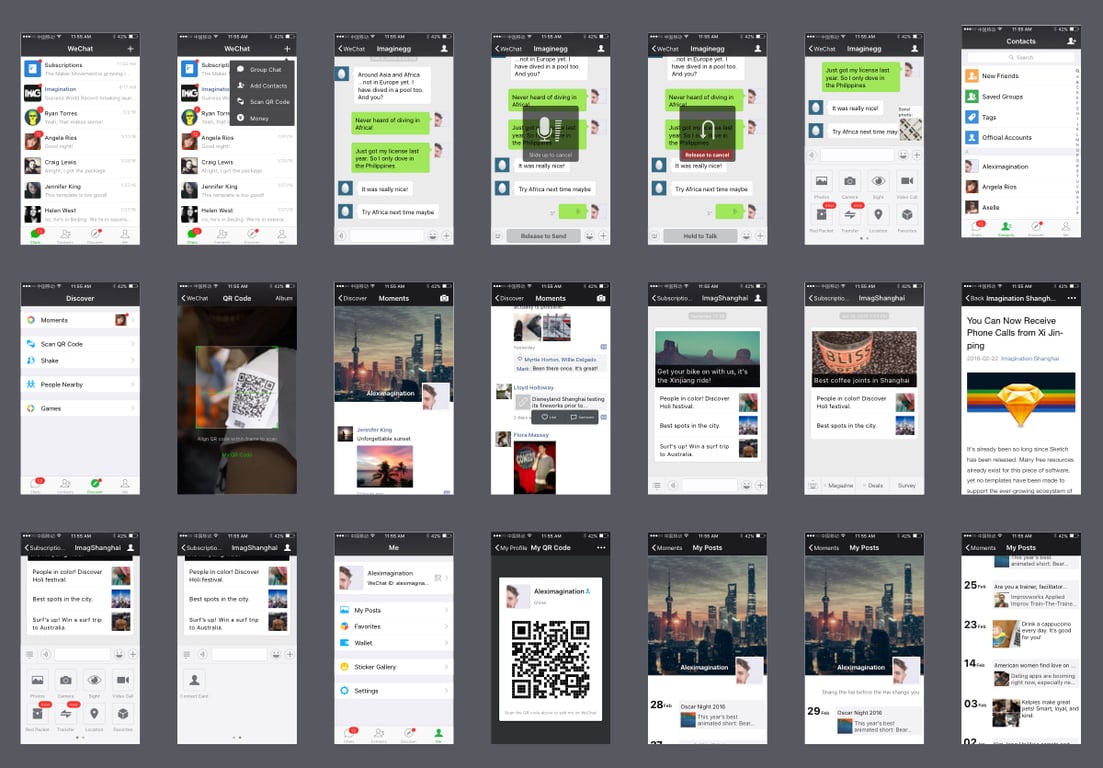

Shocked by our own firm rejections, we sat down to list out all the “obvious” reasons, aka the many innovative functions that are often praised for WeChat’s popularity. WeChat Wallet, Moments, Official Accounts, Mini-Programs, Red Packet, voice messaging, walkie-talkie…

Our list went on and on.

The “traditional” media narrative of WeChat, which emphasizes the app as omnipotent and “beyond just social”

WeChat Wallet is amazingly convenient, but so is Alipay, which is accepted by just as many vendors in the country. The Moments friend feed is a useful outlet for understanding others’ lives, but it can also lead to over-sharing, making many people — including the two of us — less interested. Official Accounts and the many “self-media” on WeChat can be sources of quality content, but in a world filled with excessive information and fake news, we wouldn’t mind taking a break from them. And the rest on the list? As much as they are fabulous perks, they are not, at the end of the day, what makes WeChat irreplaceable in our lives.

Why can’t we leave WeChat?

What are we fearing of, why are we willingly surrendering to those fears?

—

“How many WeChat contacts do you have?” in a moment of ponder, I suddenly thought to ask Yan.

“300ish. You?”

“Let me check…sh*t, I have over 800!”

Among the total 800 contacts currently on my WeChat, at least half I’ve never talked to, and there are at least another 100 that I can’t even recall the real names of. Scrolling through these unfamiliar IDs and profiles, I was struck by the power of WeChat in knowing people, or, more specially, in initiating guanxi – the rudimentary, nuanced dynamic that bonds the Chinese together in networks of personal relationships.

You might also like:

Here Are China’s Latest Plays to Fight Smartphone AddictionArticle Apr 12, 2018

Here Are China’s Latest Plays to Fight Smartphone AddictionArticle Apr 12, 2018

Just consider the below situation:

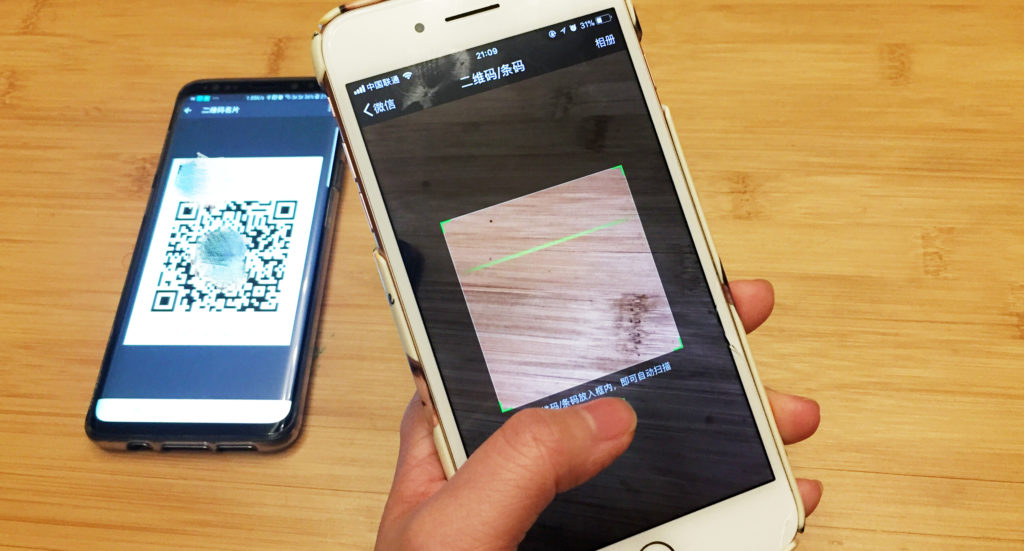

You are at a dinner party with a bunch of strangers. The person sitting next to you starts to initiate conversations. You each introduce your names, jobs and exchange name cards. You talk more about mutual interests and even discuss potential partnerships. Everything is going great, but the guanxi between the two of you isn’t officially formed until one of you opens WeChat to ask that one single important last question: “You scan me, or I scan you?” (Referring to WeChat QR code)

In all, literally all Chinese social occasions nowadays, adding WeChat has become the one and only cornerstone for manufacturing interpersonal connections. Without the gesture of scanning each other’s QR codes, all the seemingly-enjoyable physical conversations are left with loose ends untied, as the possibility of solid guanxi is still being denied.

So yes, my 800-people WeChat contact list might be overcrowded and inefficient considering the proportion of folks that I actually have contact with, but still, I cannot stop scanning more QR codes and adding more people to WeChat. Despite the fact that there are no technical alternatives (QQ is for teenagers, E-mail has never yielded mass popularity among the Chinese population, Weibo is for idol-chasing, gossiping and news updates out of the personal realm), at the end of the day, WeChat beats all by helping to kickstart guanxi the Chinese way.

“Bye for now, but let’s keep in touch on WeChat anyhow!”

—

“Shit, my phone got stolen on the subway!” the other day, a colleague of us ran into the office while crying, “I didn’t store my groups! What am I going to do now!”

It was at that moment we realized where the power of WeChat truly lies: Groups (群). As much as group chats are a common feature in most social apps, in the peculiar soil of WeChat, Groups has grown into something that truly bonds the individuals, and molds singular relationships into interwoven webs of social connections. WeChat Groups, in short, has become a reflection of the Chinese society in the digital age.

You might also like:

Tencent’s Smart Speaker Rival to the Amazon Echo Looks Set to Launch SoonArticle Apr 13, 2018

Tencent’s Smart Speaker Rival to the Amazon Echo Looks Set to Launch SoonArticle Apr 13, 2018

There are no official statistics over the Chinese usage of WeChat Groups, so Yan and I can only refer to our own life experiences to show you the diverse profile and utility of this feature. We are two working Chinese adults in our mid-20s, and here are some of the Groups we currently have:

Family/relatives Groups

Personally, I am currently in three family-related Groups: one consisting of my parents and I, and two for relatives on my mom and dad’s sides respectively. The latter two both contain members across three generations – thanks to elderly-friendly smartphones, my grandparents have turned into devoted WeChat users, obsessively sharing articles and photos in our family Group every day.

My relatives are dispersed in many different cities and countries, and our family groups have done a terrific job in gathering everyone together in an intimate manner that we never felt during the pre-WeChat era. An extra bonus? Endless red packets during festival seasons! (My 82-year-old grandfather once lovingly complained that he was on the brink of going bankrupted because of Red Packets – “WeChat is making me broke!”)

Advanced Red Envelope TechniquesArticle Feb 14, 2018

Advanced Red Envelope TechniquesArticle Feb 14, 2018

Work-related Groups:

As long as you are working in China or with Chinese people, chances are you are in at least one work Group on WeChat. They are the ones that you can’t mute (a considerate function of WeChat, which allows users to mute some of the chats and eliminate pop-up notifications), can’t delete, and in most cases have to purposely hang to sticky status (again, another very considerate in-app function). They destroy your weekends, break your work-life boundaries, and make holidays utopian. Unless you have the guts to declare WeChat-disappearance from your boss, you can expect endless in-group “@” that reminds you of your never-ending workloads anytime, anywhere.

Rants aside, we have to admit Groups really do a superb job in boosting productivity and, more importantly, cultivating interpersonal connections. You might have never met some of the group members you are working on a certain project with, but by adding them as your personal WeChat contacts, you are instantaneously granted entry into a more private dynamic of their lives with the potential to foster personal connections. Doing business in China is all about relationships, and Groups, under the name of work, is the best place to start your relationship-cultivation.

Old classmates/friends/social organization Groups:

I know we are tossing a lot of things together under this category, but really, what we mean is the kind of Groups that you feel you socially belong to yet are not really bothered to engaged with on a regular basis. Most of these Groups are large in size (at least 20 people) and can be filled with members you are not exactly familiar with. Still, by putting them on mute and only checking occasionally, you get to keep up with occasional gossip, or even catch some red packets from random acquaintances.

Red packets in action

But not of all these Groups are “boring” or “useless”. When we asked our Chinese friends what their most-treasured WeChat Groups are, someone showed us a “Sticker-battling” (斗图) Group, where members constantly bash each other with self-made stickers and communicate through these creative visual expressions. From stickers of Peppa Pig and Gavin Thomas to Jiang Zemin, Groups like this one have acted as incubators for endless internet memes, providing young Chinese with a new language and space for entertainment.

Peppa Pigs, Thomas Gavin and Jiang Zemin – China’s hot Sticker Stars, being circulated all around WeChat

Since 2016, WeChat has gradually taken a stricter approach over the management of WeChat Groups. In addition to restricting the maximum Group members to 500, it has also reinforced the role of group “host” (群主), a specific individual that is legally responsible for all the in-group speeches and activities. Such policies are WeChat’s way of negotiating between the government and its users (now over a billion of us!): ever since WeChat launched in 2011, Chinese users have been utilizing Groups to run everything in the grey area, from pyramid-selling and gambling, to the sharing of porn and “incorrect political information”.

WeChat Groups for illegal loans (left) and porn (right)

As the old Chinese saying goes, “when the top has plans, the bottom always has counter-plans” (上有政策,下有对策). Despite tougher regulations, many Chinese today are still using WeChat Groups to leverage business interests, express political views or discuss social issues. “Some of my friends will send out ‘dangerous’ news in our group, wait for 2 minutes, then withdraw it in a flash,” says a friend we interviewed. “It is a useful and perhaps the last resort for us to see the other side of the story without getting everyone into trouble.”

—

On March 26th, Robin Li, Baidu’s founder and CEO, spoke at a national forum. “Chinese users are generally less sensitive/more open towards privacy,” he declared. “If the loss of privacy means greater convenience and security, in most cases, they are happy to accept the deal.”

The speech sparkled a wave of criticism among liberal Chinese netizens, but having reflected upon our own relationship with WeChat, we have to admit Li’s verdict holds some truth. Everyone knows there’s no such thing as privacy any more in the digital age, and everyone is aware of the fact that WeChat is the most censored app nowadays, but honestly, so what?

To deconstruct the “so what” a bit further, we are confronted with two strands of reality.

For one, there’s simply no alternative to WeChat for anyone living in today’s China: it is the single must-have app for everyone’s home screen, the app that gets everything done and connects everyone in a most norm-conforming, efficient manner. For two, we genuinely just need the app, so much that sacrificing a bit of privacy is tolerable.

With multiple layers of relationships saturated in a single app, WeChat has becomes the place where everyone finds their identities, understand their values, and fulfills their responsibilities in wider society.

As Chinese, it is only by forming guanxi that we come to the being of ourselves. In today’s mobile-empowered China, the best, and perhaps only channel to complete such a process is WeChat.

Sign up to the Elephant Room newsletter here.

You might also like:

Long-Time Google Employee Quits, Accuses Company of Copying WeChat (Among Others)Article Jan 25, 2018

Long-Time Google Employee Quits, Accuses Company of Copying WeChat (Among Others)Article Jan 25, 2018

How WeChat Became the First Chinese App Entered into a Museum CollectionArticle Jan 20, 2018

How WeChat Became the First Chinese App Entered into a Museum CollectionArticle Jan 20, 2018