From June 2 to 4, Chinese art director Tianzhuo Chen staged his latest show, Trance, at Kampnagel in Hamburg, Germany’s most prominent independent venue for performing arts. Over nine hours and six chapters, the durational performance installation lulled everyone — performers and audience members — into a trance.

The performance, which premiered at the M Woods art museum in Beijing in 2019, could only be brought to Europe three years later due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The team will hopefully perform the show again in Berlin in February 2023.

Since the global pandemic, performing arts have taken on new layers of meaning. In Trance, for example, the very act of congregating for a live performance is cause for celebration and a unique collective experience.

The work’s titular meaning ties in with bardo, the intermediate stage between death and rebirth in some schools of Buddhism.

“I aim to form a shared state of consciousness in a space,” Chen tells RADII.

Born in Beijing in 1985, Chen is known for his post-internet mythologies. His works can be seen as a testament to both radical modernization and archaic relationality. In 2015, Chen, who is on a constant search for community, rounded up an entourage of artists and founded the label Asian Dope Boys (ADB).

The night of June 2 is when we finally experience Trance for ourselves.

Memorable from the start, Trance requires entering a heat-filled psychocosm. Performers linger in the nebulous atmosphere, and a crane-suspended guitarist slowly plucks his instrument next to an inflatable heart with a worm peeking out from it.

The scene is inspired by a series of Japanese paintings that portray a decaying female corpse. The visceral theme of corporeal putrefaction reflects human impermanence, a core tenet of Buddhism.

This introductory scene embodies a central characteristic of Chen’s artistic aim: To alter the spirit of the popular, to position it next to religious spirits, and to shift between the ideal and the material, the sacred and the profane.

He creates a new dynamic of encounters through the force of assertive subversion in Trance. It recalls an overarching sense of collective process fueled by associative powers and intuition.

When we sit with Chen in his backstage dressing studio, performers keep wandering in. Chen asks the crew to don flashy T-shirts designed by Bali-based artist Ican Harem, one of Trance’s many highly skilled collaborators.

The realm of performance sees a culmination of ADB’s experimental practices, which unify painting, sculpture, installation, video, music, and fashion. They engage the scripted anarchy of Chen’s artistic approach with a skilled affinity for transgression and endurance.

In a larger sense, the performance’s cyclical narrative wavers between the mythological and the religious. Chen’s creatures inhabit a liminal state with undefined boundaries while signaling a deep understanding of relatedness. They remain in constant transition between different physical and spiritual states, vibrating with heaven and hell through fluidly changing scenic patterns.

Besides Buddhism, the dramaturgical process incorporates the psychoanalytic writings of C.G. Jung (particularly in The Red Book), surrealist Réne Daumal, and K Allado-McDowell. A disembodied narrator informs the audience that the performers’ journey represents a search for something vague, an imaginary mountain that “locates the inferior heaven at its foot.”

One scene is a perfect example: In an analogy to Daumal’s allegorical novel Mount Analogue, performer Omid Tabari, aka Shadow Licker, pushes an immense boulder through the space.

Chen’s experiments and efforts to represent the realities of inner experience are embedded in the poetic cosmology of a self-created artistic ‘religion’ called Adaha.

Adaha is the god, idol, and superstar that appears in his works as a figure representing an all-encompassing witness, an ‘all-seeing eye.’ The eye of Adaha is reminiscent of the Eye of Horus, the Egyptian symbol of the door to the soul, an embodiment of state power and divine benevolence that watches over human civilization.

“I would like to see each performance as something like a ceremony. So maybe, in that way, the mode of storytelling itself does approach the way religions are constructed,” said Chen during a previous interview.

This time, Adaha’s eye appears on a gigantic T-shirt sculpture that hangs above the dance floor and continuously cries throughout the show. The liquid drips into a little pond below, evoking the scenic surrealism of a fairy tale park.

Chen also employs spiritual traditions to interpret contemporary Chinese society’s capital-driven developments. Iconography such as religious totems, commercial logos, and pop culture icons convey a sense of endless incorporation, absorption, and ejection.

As the performers march onto the main stage, they remove their streetwear hoodies while carrying out folk dances — a gesture of unlearning their imposed socio-cultural conditions. Chen then invites the audience to enter a state of possession, visit the performance’s various hells, and witness an in-between state of traveling.

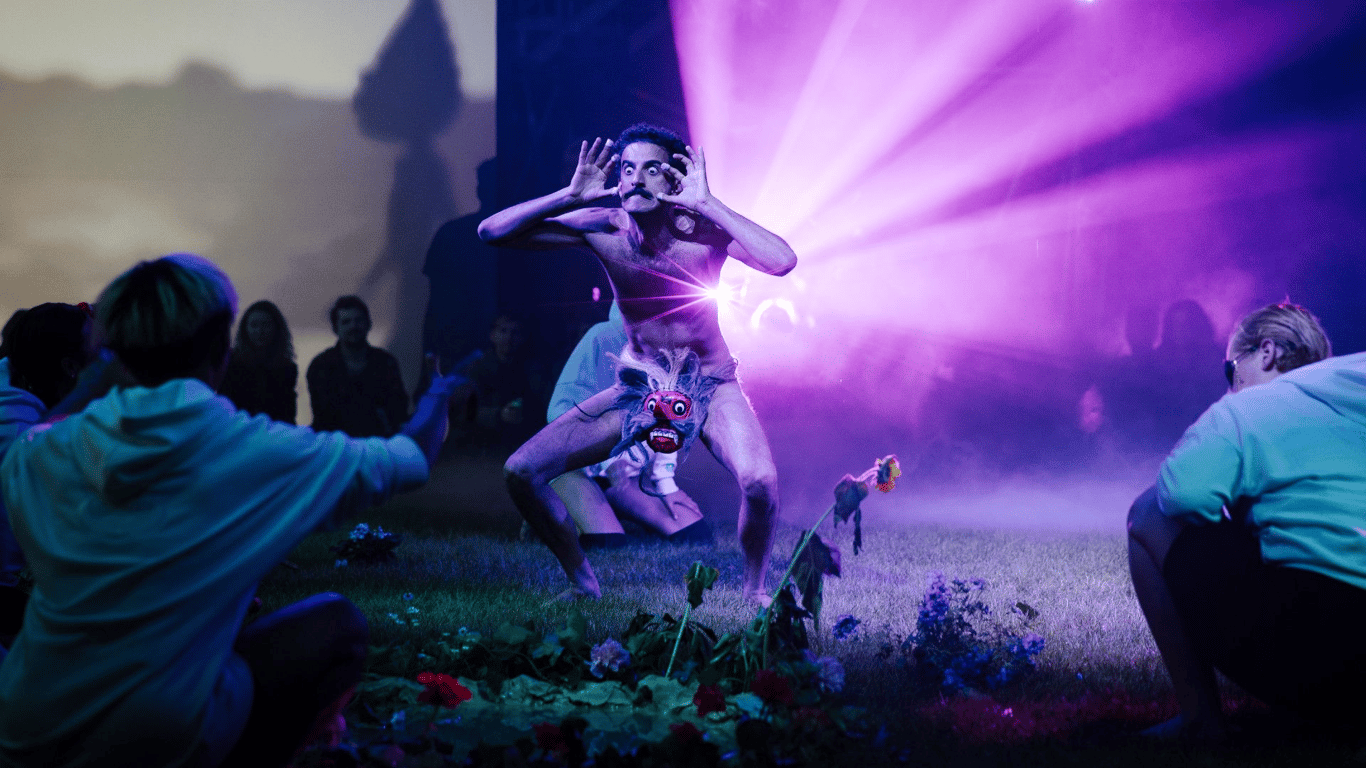

In a series of solos, performer Yiva Falk, wearing long fire-red braids, strikes us as a stage presence inspired by Barong, Bali’s panther-like king of the spirits.

Indonesian artist Siko Setyanto also presents an eye-catching performance that merges classical ballet and Javanese dance.

Drawing inspiration from 12th-century Japanese paintings of the Buddhist Hells, also known as Jigoku-Zoshi, their solos strike me as haunted biographies of bodily reincarnation — or raw and bloody spiritual lessons to aid the audience’s understanding of sin.

One of Trance’s most drawn-out segments takes place on a circular grass floor with stage elements and projection screens on one side. An inflatable frog stands guard; the poisonous creature sits upon the roof of a Southeast Asian bamboo hut — a symbiotic arena that blurs the relationship between the human, the non-human, and the spiritual in ways that exceed categorical value judgments.

In the style of 19th-century panoramas, the side screens depict Chen’s earlier works, namely some films recorded in Tibet. These showcase Tibetan Cham rituals, which highlight dance as a skillful spiritual tool and monastic practice employed since time immemorial.

As the evening progresses, the scenic ritualistic setting dissolves into a rave-like immersive experience.

The cathartic finale has a heated vibe and unfolds amid a club-like atmosphere. Heavy vibrations spread across the space. Bodies allow their exhaustion to be seen in a shared yearning to return, dance, and inhabit a sphere of consciousness between all present at this moment in the space.

Perhaps the notion of Trance can be best understood as a claim for artistic freedom, articulated on a transcultural and collective level, wrapped in the terminology of the archaic, mystical, and magical. The attempt to abandon what we imagine as ourselves is an unspoken invitation to experience diverse modes of ‘othering’ in exchange for liberation.

This sensuous, intimate, and contemplative experience of the performance leaves us with an afterglow that lasts for days.

All images courtesy of Kampnagel