If you grew up in the Chinese mainland and haven’t spent time in the United States, chances are you’ve never crossed paths with the mythical “Chinese” dish known as General Tso’s Chicken. For many Chinese diners, finally trying it can feel like discovering an alternate-universe version of home cooking—sweet, tangy, and strangely familiar despite having zero roots in actual mainland cuisine. Maybe an international friend has dropped the name in conversation, hoping to bond over “Chinese food,” only to be met with polite confusion. So let’s settle it once and for all: where does General Tso’s Chicken actually come from?

For anyone who’s never encountered this dish, think of it as sweet-and-sour chicken’s flashier, better-dressed cousin. General Tso’s Chicken is all about crisp, deep-fried bites wrapped in a thick, mirror-gloss sauce. Yes, it’s sticky and borderline “goopy,” but for people who grew up eating it, that syrupy glaze is pure comfort—fragrant, familiar, and low-key nostalgic. It’s a cornerstone of countless Chinese-American restaurants, and its many variations pop up in Asian fusion spots across North America and even parts of Europe. And honestly, ask an American where they first learned to use chopsticks and you’ll get a surprising number crediting the General himself.

For diners from the Chinese mainland, though, the whole thing sounds… weird. We don’t know General Tso’s Chicken—but we do know General Zuo (左宗棠, Zuo Zongtang). In school textbooks, he’s immortalized as a slim Qing-era official with a half-shaved head and a serious beard, best known for quelling a major rebellion in Xinjiang and holding the Qing empire together using sharp military strategy. Not exactly the kind of guy you picture being turned into a glossy fried-chicken icon.

So how did this historical figure get tied to a plate of tangy chicken? Plot twist: he didn’t. The dish was actually created in the 1950s by Peng Chang-kuei (彭长贵), a chef from Hunan who later brought it to New York. That’s where it morphed into the sweet, crunchy, neon-sauced version we know today. And no, it’s not the same as sweet-and-sour pork (gulao rou 咕噜肉), though they share that punchy, tangy DNA.

Variations of the dish crop up outside the United States too. Canada and Australia have their own parallel versions thanks to similar Chinese-Western food histories. In the United Kingdom, sweet-and-sour chicken balls fill the same cultural role, while Chinese restaurants in places like Greece and Germany riff their own local twists on sweet-sour chicken—though none are exactly General Tso’s. At its core, the dish is a uniquely American invention that spread through the West’s Chinatowns and kept evolving.

Of course, the world is full of “Chinese” dishes that don’t actually exist in the Chinese mainland. Think of the so-called “Indian flying pancake” in Southeast Asian night markets—or even in China itself, where Chongqing-style chicken pot wasn’t born in Chongqing at all, but invented by Fujianese restaurateurs. Dishes travel, they mutate, they shed their backstories and pick up new ones. That’s the beauty of global food culture: transformation is the norm, not the exception.

So the next time the table breaks out into a debate about “authenticity,” do a playful cross-country cupping of all things sweet-and-sour chicken. It’s a reminder that food, like people, rarely stays in one place—and that’s what keeps things interesting.

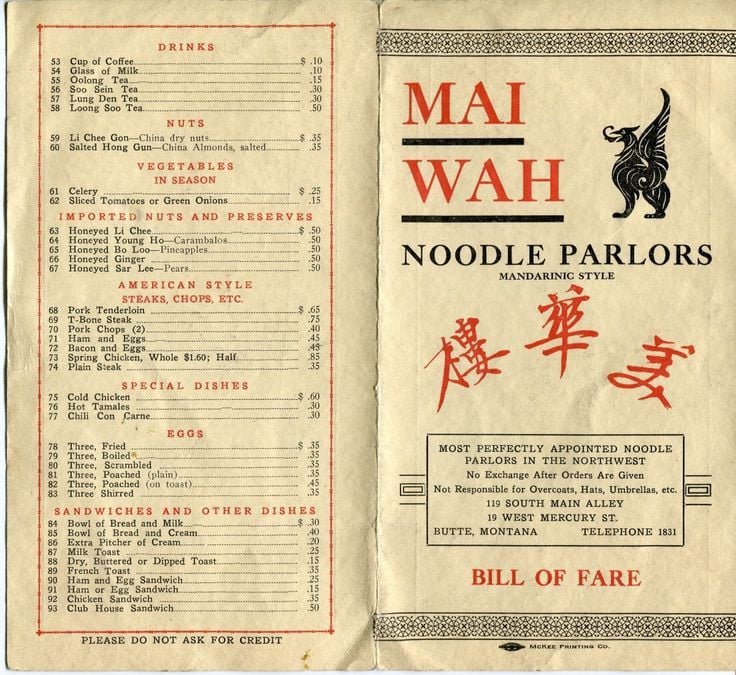

Cover image via Vice.