I’m gonna say it upfront: Hakka food is my Roman Empire. It doesn’t seduce you with the glossy opulence of Cantonese dim sum or the minimalist clarity of Teochew steamed fish. Hakka cuisine is quieter, almost secretive—like the people who created it. It’s the taste of migration packed into a single bowl: resourceful, stubborn, and highly adaptive.

My proper introduction to the cuisine came years ago, right after I landed in Singapore. I wandered into a tiny coffeeshop in Tanjong Pagar and ordered something called “lei cha fan”—or “thunder tea rice”—because the name sounded dramatic. What arrived was deceptively humble: a mound of rice crowned with seven or eight kinds of chopped vegetables (bitter choy sum tips, sweet mani cai, crunchy long beans, preserved radish that snaps like gossip), scattered tofu cubes, toasted ikan bilis, peanuts, and a small bowl of electric-green soup on the side.

You smash the pesto-like paste at the bottom of the soup bowl—ground tea leaves, basil, mint, mugwort, sesame, peanuts—dilute it with hot water, then flood the rice. One mouthful and it hits in waves: bitter, nutty, herbal, then instantly soothing. It’s warm but wakes you up. It tastes like someone’s grandmother scolding you for not eating enough greens, then hugging you right after.

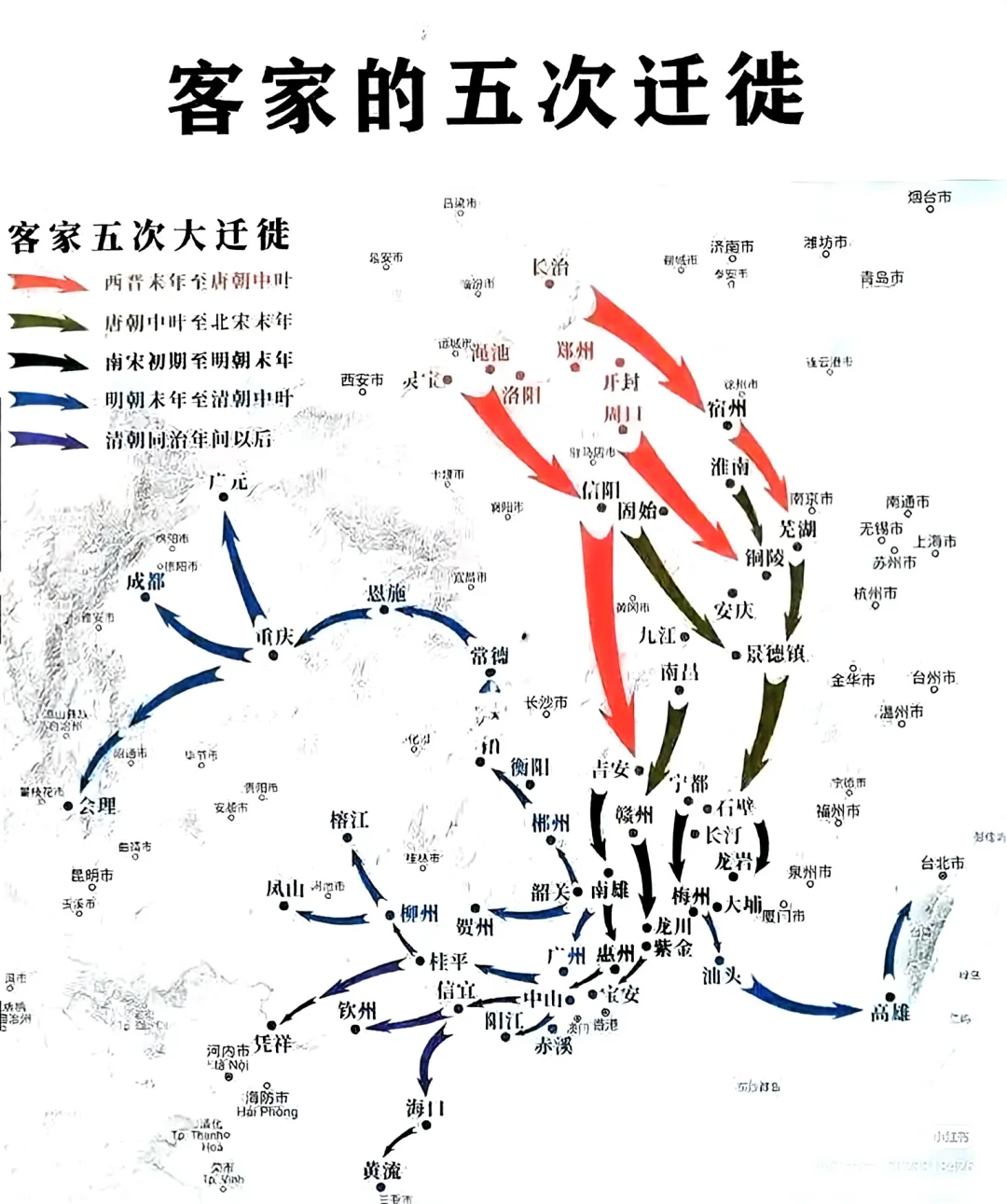

The name “Hakka” literally means “guest family” (客家). For over a thousand years, these were the Han Chinese who kept getting evicted—by war, famine, invaders—from the Yellow River heartland down south, wave after wave, from the Jin dynasty through to the Song, until they washed up on the rocky cliffs of Guangdong, Fujian, and Jiangxi. They called themselves “guests” because that’s what they always were: the latecomers, the outsiders squeezing into mountain cracks while the fertile plains were already spoken for.

A millennium of war, famine, and survival that pushed an entire people south — and eventually across oceans.

And Hakka women? They ran the show. While men farmed terraced plots or sent remittances from Southeast Asia, women stretched one chicken across three meals, salted mustard greens until they’d keep through monsoon season and war alike, and pounded wild herbs into medicine when doctors were a fantasy.

That’s why Hakka food never became its own flashy “eighth great cuisine” in China (China officially recognizes eight major regional cuisines—Sichuan, Hunan, Cantonese, Fujian, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hunan, Anhui, and Hakka still isn’t on the list). That’s the point. In Fujian, dishes borrow sour-spicy vibes from Minnan; in Guangdong, it hides inside Cantonese menus as “Dongjiang dishes”; in Taiwan, it’s just considered “mountain food” because the Hakka arrived last and took to the hills again. It’s the ultimate diaspora cuisine before diaspora was cool. It’s adaptable, unapologetically salty-fatty-fragrant (鹹香肥), and built for people who sweated all day reclaiming the land.

Back to what to eat, try mei cai kou rou (梅菜扣肉), where layers of pork belly are braised and steamed with preserved mustard greens until the fat renders and the greens turn savoury-sweet. Or abacus seeds (算盘子), chewy taro dumplings pressed with thumbprints to look like abacus beads—a subtle nod to the merchant mindset that shaped Hakka life.

The high salt count in a lot of dishes replenished what they had lost swinging a hoe under the tropical sun. The fat kept them from starving when harvests failed. The fragrance—shallots crisping, ginger exploding, preserved veggies funking up the wok—was sensory marketing at its best: make the rice smell so good you’ll eat two bowls and have enough energy to keep going. Even lard mixed rice (豬油拌飯) was once everyday fuel—not indulgence.

And thunder tea rice? It’s the OG survival meal. Legend says it cured Zhang Fei’s plague-struck troops in the Three Kingdoms era—three “raw” things (生 tea, 生 ginger, 生 rice) pounded into soup. But the real history is more humble: when the Hakka were fleeing south, they fried grains and tea leaves, packed them light, and whenever hunger hit, they’d bash everything in a bowl with a guava branch, add hot water, and then done. Portable, vegan by necessity, and stupidly nutritious. Today, in Meinong, Taiwan, grandmas still use mortars the size of bathtubs where the pounding sounds like actual thunder—hence the name.

In Singapore and Malaysia, the dish went full tropical: ikan bilis for umami, kailan, sometimes kolo mee or beehoon instead of rice, because, why not? In Taiwan, it got sweeter, almost dessert-like, as they finally had sugar and peace. In Mauritius or Jamaica, it’s whatever bitter leaves grow locally. Same DNA, new postcode.

These days, when I’m homesick for a home I’ve never fully had, I spend a Saturday at Shanghai’s wet market begging aunties for mugwort and sweet leaf, then bash herbs in my tiny kitchen until my shoulders burn. The smell—sesame oil smoking, tea leaves frying, basil surrendering—hits harder than any therapy. I plate it up for my friends and watch the ritual: suspicion, grimace at the bitterness, silence, then “wait… pass the peanuts.”

In that green-stained moment, we’re all temporary Hakka; guests at a table that’s been moving for a millennium, finally allowed to sit down and eat.

So, yeah, I’m biased. Hakka food isn’t the prettiest or the most famous, but bite into a cube of stuffed tofu oozing pork and wood-ear, or slurp that impossible green soup, and you taste something louder than any Michelin star. It’s resilience, rendered edible.

If you’ve never tried thunder tea rice, fix that.