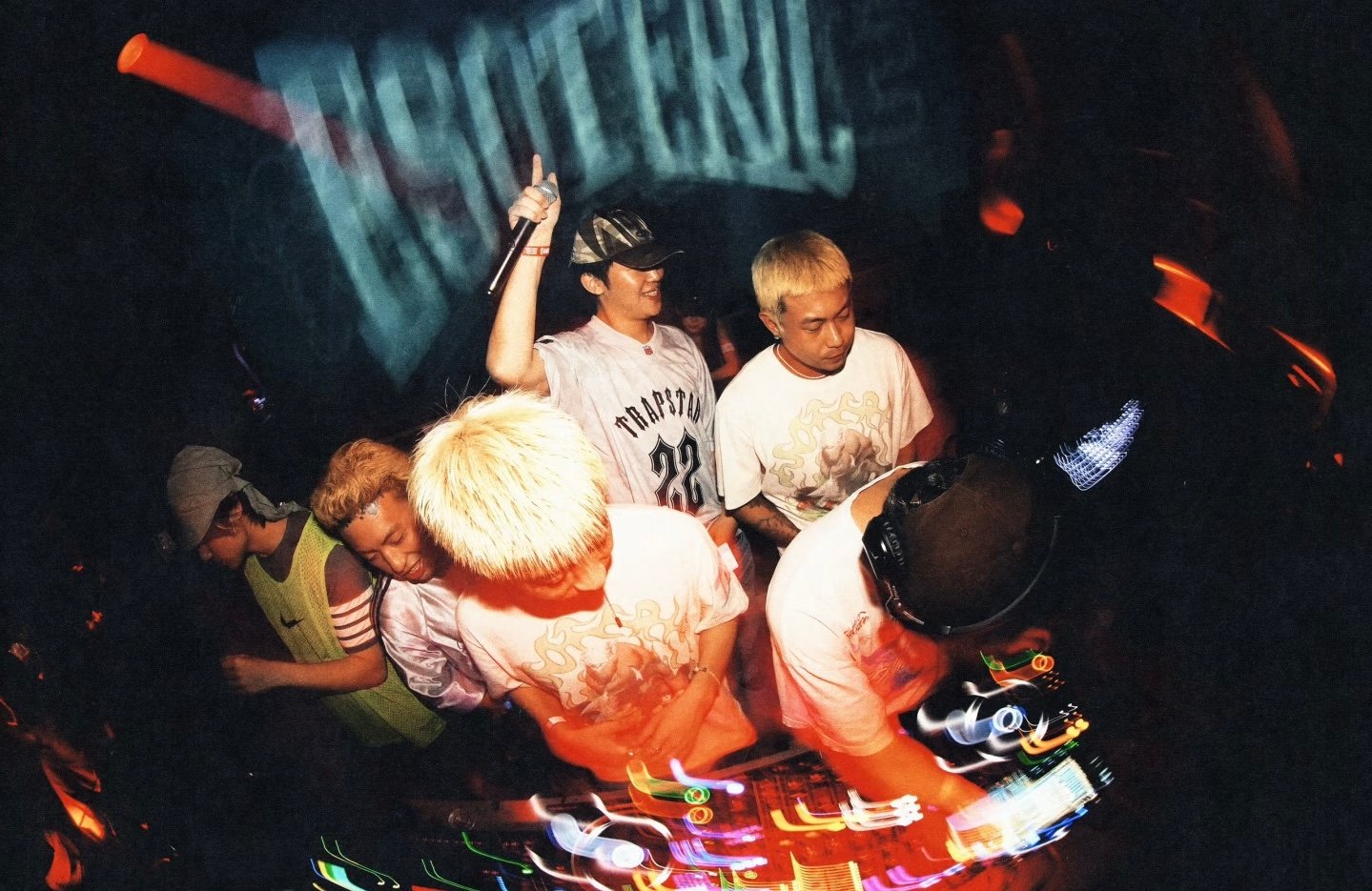

On a Saturday in December last year, Billy Cai had a rare moment of certainty. His five-year-old streetwear label, ESOTERIC THING, was collaborating with Nike for the first time. For a small, independent brand that has never opened a permanent store, the partnership felt monumental.

“It’s definitely a milestone,” Cai admits. “But more than that, it opened a door.”

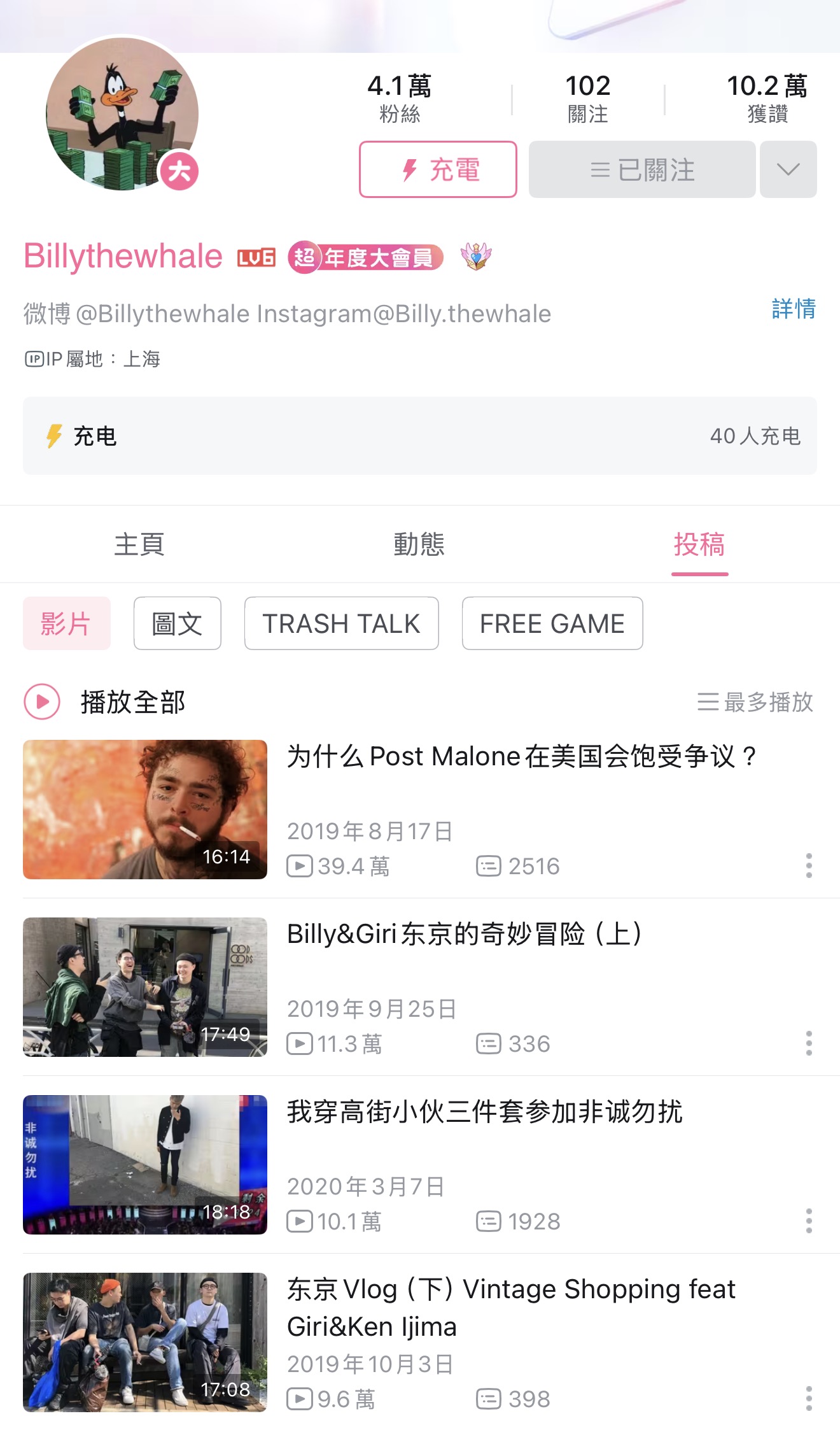

Before founding his label in 2020, the Chongqing-born creative was better known online as Billythewhale, a content creator on Bilibili, China’s YouTube equivalent. His videos—loosely edited, sometimes rambling, often reflective—ranged from personal vlogs and cultural commentary to opinions on fashion, brands, music, and social issues. He now has over 40,000 followers on the platform, but he never treated it as a business tool. “I never thought of myself as a KOL,” he says.

Still, the idea of starting his own label had been quietly forming for years. Cai studied in the United States and grew up immersed in street culture. In 2017, he returned to China after completing his studies and settled in Shanghai, one of China’s most dynamic cities and an obvious fashion capital.

At the beginning, there was no founding mythology, no grand vision statement, not even a carefully chosen name. “The name actually came from a friend,” Cai explains, almost apologetically. “He used the word a lot. I thought it sounded cool. When I needed a name, I just thought of that.”

If the naming was improvised, the early operations were even more so. Cai admits that when he launched ESOTERIC THING in 2020, he had no business plan, no design training, and no experience in production. For the first six months, he worked entirely alone. His first product—a T-shirt—was designed in PowerPoint and sold on Taobao. The initial sales were purely driven by his Bilibili followers.

However, that honesty has since become the essence of the brand. “That’s why Nike chose us,” Cai says. “Everything we do is real. What you see is what it is.” In an era when streetwear brands are often engineered for virality, ESOTERIC THING grew instead from trust.

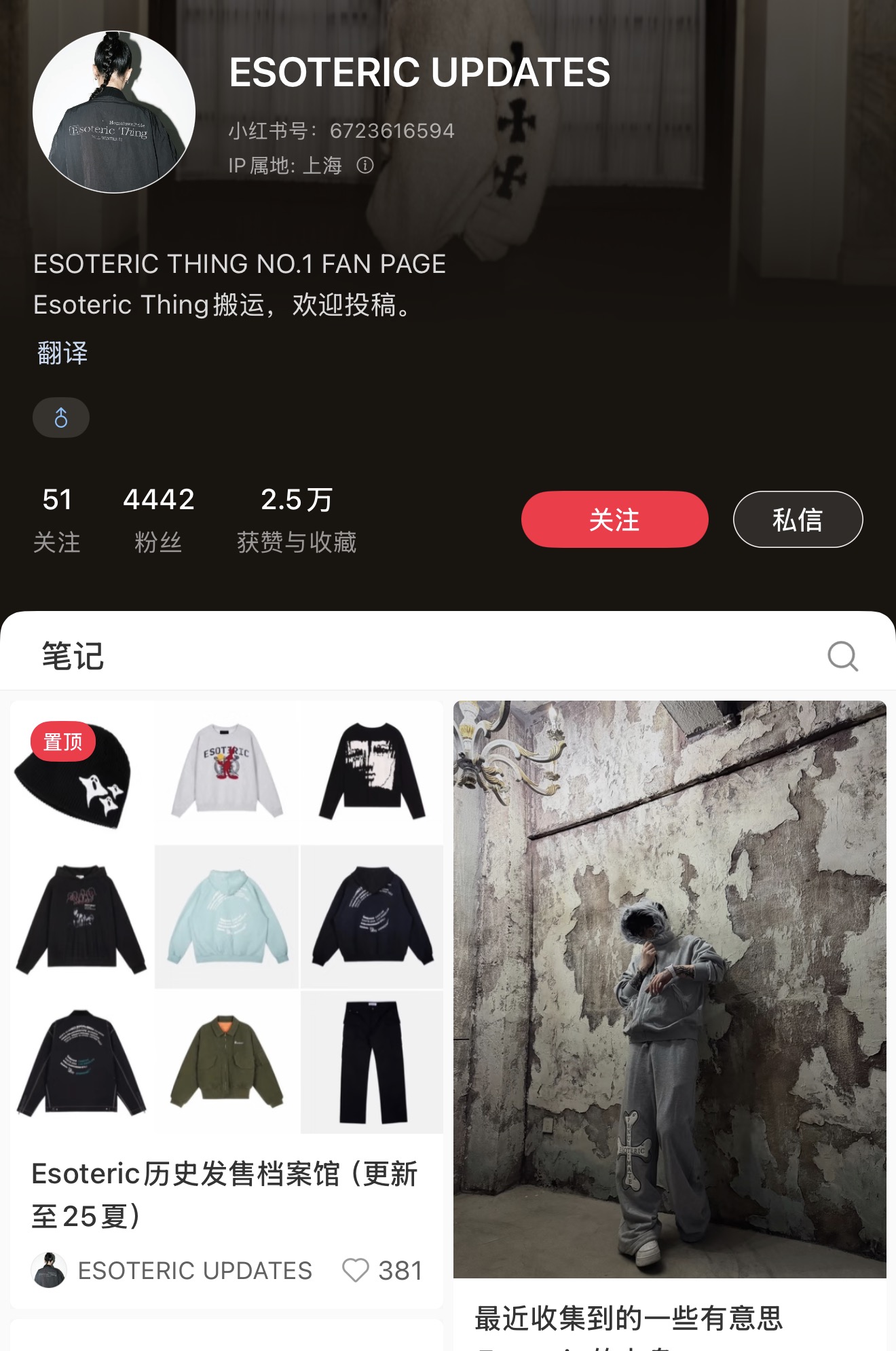

Today, that trust has translated into a distinct community. On Xiaohongshu, the brand has over 14,000 followers, and even more tellingly, a fan-run account dedicated to documenting and analyzing ESOTERIC THING and Cai himself.

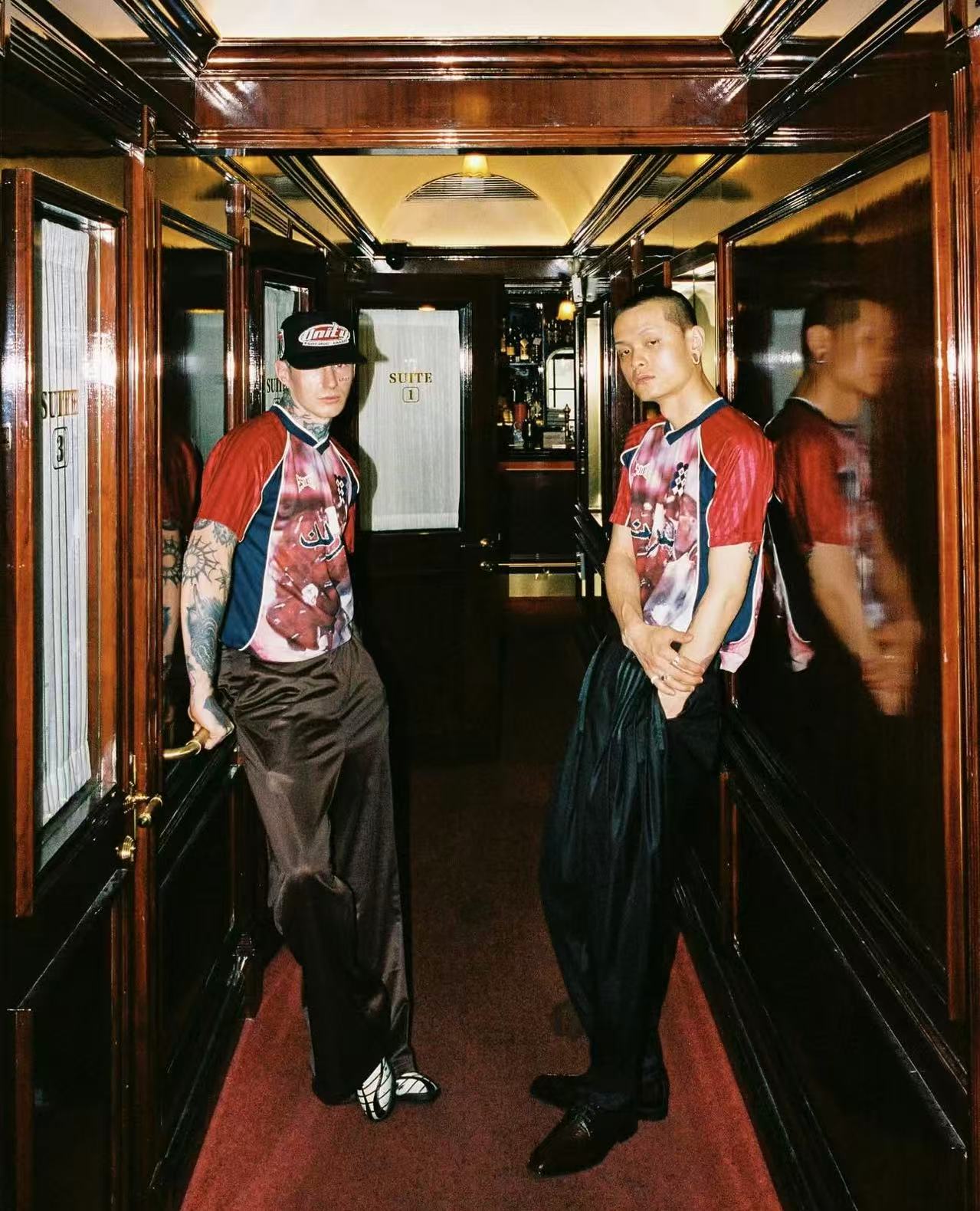

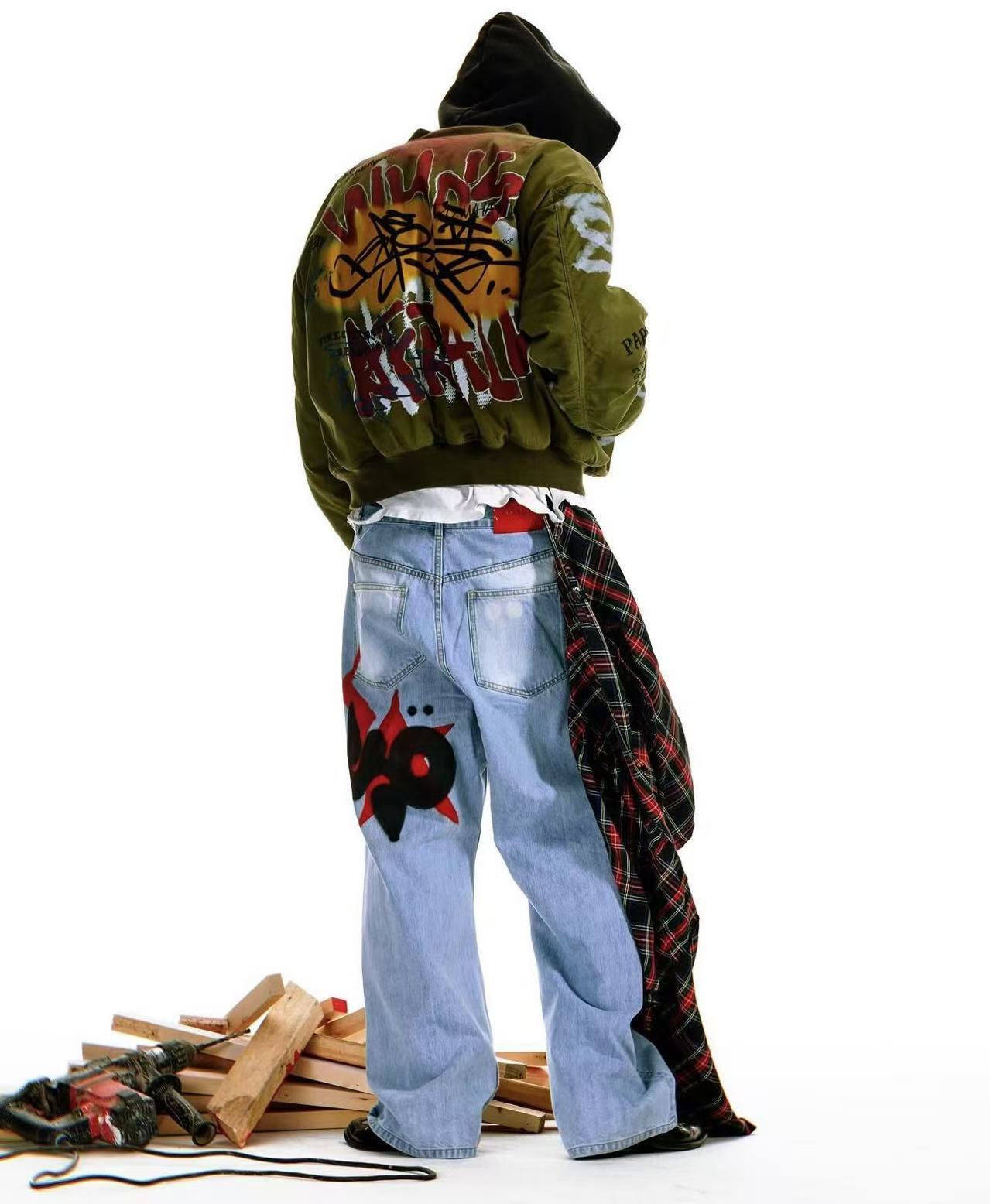

Visually, the label’s vocabulary is consistent but understated: hats, football jerseys, embroidery, motorsport references, race cars. But Cai resists the idea that the brand is driven by symbols or slogans. Instead, he describes its spirit as a “quiet rebellion.”

“It’s not the kind of rebellion you see in early streetwear,” he explains. “Not shouting, not swearing, not trying to shock you visually. Ours is calmer. Sometimes we hide information in the details. Sometimes, just choosing to do this kind of brand, in this context, is rebellious enough.”

That restraint also extends to storytelling. Cai is deeply sceptical of narrative-driven marketing and rejects the idea that clothes need to be explained. “If you see something, that’s what it is,” he says. “I don’t want to over-interpret designs. At the end of the day, it’s a garment, not a manifesto.”

ESOTERIC THING’s rise came at a time when a broader shift was—and still is—happening in Chinese consumer behavior. Over the past three-to-four years, domestic labels have moved from alternatives to anchors, as trends such as guochao and the so-called “New Chinese Style” reframed local brands as sources of cultural confidence rather than compromise. The pandemic accelerated this transition: with overseas travel curtailed, spending was redirected inward, and Chinese consumers were forced to look closer to home.

That recalibration extended well beyond fashion. From Labubu-producer POP MART to bubble tea chains like Mixue, and more recently, the global attention drawn to Chinese AI start-ups following the DeepSeek moment, local brands have increasingly proven they can generate both scale and cultural resonance.

In this climate, the question shifted from whether Chinese brands could succeed globally to how they would define themselves in the process. ESOTERIC THING emerged within this transition, but notably resisted its more performative impulses.

In a Chinese market increasingly saturated with guochao labels—a term Cai neither embraces nor actively rejects—his brand occupies an ambiguous position. It refuses to present itself as explicitly Chinese, yet never distances itself from its origins. “Why does a brand have to prove it’s international by leaving China?” he asks. “From the very beginning, we already had overseas customers.”

Indeed, its appeal has quietly extended beyond China, with international buyers drawn less by cultural signaling than by sensibility. Cai believes that ambiguity is part of the brand’s strength.

Offline, ESOTERIC THING has deliberately remained nomadic. Rather than opening a permanent store, the brand has relied on pop-ups since late 2023. “Pop-ups allow us to experience offline consumption without making a huge commitment,” Cai explains. “They help us understand what people actually care about.”

The approach is also pragmatic. Opening a store, he says, is “a serious promise”—one he doesn’t want to make prematurely. “If we open a store, it has to be something we’re truly satisfied with,” he states.

One of those lessons came from a pivotal moment in December 2023, when the brand collaborated with graffiti artist Donis for its first major pop-up. Donis, a Uyghur artist from Urumqi, is known for blending English, Uyghur, and Chinese scripts into a distinctive handstyle presentation, and has previously worked with Balenciaga on global campaigns. The pop-up sold out completely and briefly propelled ESOTERIC THING into the mainstream spotlight.

At the time, Cai thought it marked a turning point. “I believed we had entered a new chapter,” he recalls. “But later I realized that sales can be misleading.” The success, he says, created an illusion of maturity—a sense that the brand had arrived before it was truly ready. “We were still lacking in many areas.”

As ESOTERIC THING’s visibility increased, so did skepticism. Pricing, in particular, became a recurring point of contention. Some consumers questioned whether a relatively young domestic streetwear label should charge what it does for denim or outerwear. Others, accustomed to mass-market guochao price points, struggled to reconcile the brand’s understated design language with its positioning.

Cai doesn’t shy away from these debates, instead refusing to resolve them for the audience. “Pricing is a choice,” he says matter-of-factly. “You choose who you want to sell to. Consumers choose whether to support you. Both sides are fair.” To him, disagreement is not a failure of communication, but a natural process of mutual filtering. “If people think it’s expensive, that’s okay,” he adds. “Everything has consequences.”

Looking ahead, a permanent store remains a long-term goal for ESOTERIC THING, but only under the right conditions. Five years in, the Chinese streetwear label exists in a state of deliberate incompletion. It is neither fully underground nor comfortably mainstream; neither loudly Chinese nor carefully international. Cai seems content with that ambiguity, and that, along with the small community that grows with him, ultimately makes the label a distinctive voice.

Cover image via ESOTERIC THING.