Image via Trover

The 798 Art Zone spans a quarter-square-mile area outside of Beijing’s city center, between the Fourth and Fifth Ring Roads. In other words, it’s on the periphery, much like contemporary art’s relationship with “normal” society in China. Indeed, contemporary art here does not operate within the government’s ideological agenda of promoting China’s rich cultural history, but instead attempts to remain beyond its grasp as a niche community .

On the surface, 798 appears to be a sprawling area of shops selling “Chairman Meow” prints and people posing for wedding photos next to graffiti or public artworks. But look closer and you’ll find more than kitsch and tourists. About 20 of China’s best galleries and museums for contemporary art are here, places that put 798 on the map in China and beyond.

Originally founded in the 1950s as an area of Bauhaus-style factory buildings for the production of military equipment, 798 was abandoned for decades before artists began using these large spaces for studios and exhibition spaces in the early 2000s. The conversion of factories into art spaces should sound familiar—it’s precisely what happened to Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood in the 1960s. Like its counterparts in New York, London and Berlin, 798 has grown as studios have given way to galleries and restaurants. And yet, 798 stands apart. While living costs have indeed driven some artists even farther into the city’s periphery, inflation hasn’t been nearly as drastic as in various Western art hubs.

I usually spend five days a week in 798 behind my desk, but for this piece I thought I’d venture outside and make the rounds for a day.

Entering from the west gate, I see a huge line of maybe 100 people (not abnormal in China) encircling a central square. The Japanese art collective teamLab’s exhibition has just opened at Pace Beijing, and its “digital playground” is attracting the mass audience that the artists aim to reach. At 100 RMB (15 USD) per ticket to visit a commercial space, I’m not willing to queue up in the summer heat, but I enter the square anyway to appreciate the exceptional vantage on 798’s most interesting buildings and public artwork.

Encircling the queue are some of the last remaining Bauhaus-style factory buildings, their designs replete with alternating geometric forms and large skylights along their roofs. Installed at the square’s center is an airplane wing — a work by Xiamen-born French contemporary artist Huang Yong Ping. A life-sized reconstruction of the US spy plane that collided with a Chinese fighter jet over Hainan in 2001 and was forced to land, then sent back to the US in parts, the Bat Project has been censored in all three of its iterations. And yet, “Bat Project III” was, somehow, later installed here in 798, where it remains to this day. Finding Huang Yong Ping’s work in China isn’t easy (as you can imagine), but he’s often foregrounded in exhibitions abroad. For instance, the Guggenheim’s upcoming show of Chinese art – Theater of the World – is named after his work.

There are hundreds of art spaces in 798, and they run the gamut: some display tacky ink paintings, others participated in Art Basel. Over the past couple of years, the number of the latter has increased, with spaces like Platform China and Urs Meile moving over from Caochangdi (the less commercial art district housed in a compound designed by Ai Weiwei, just 10 minutes away from 798). The first Gallery Weekend Beijing (modeled after the Berlin event) in March neatly brought together 798’s best galleries and gave them a juried prize as incentive to mount their best exhibitions.

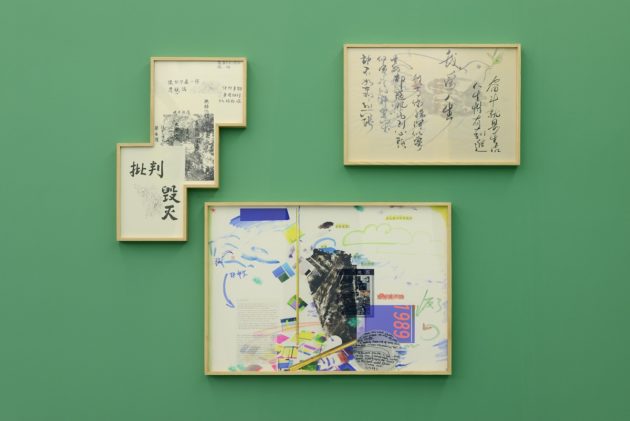

I usually hit up Long March Space and Boers-Li Gallery, both of which have exhibition programs of the most historically significant and/or internationally renowned Chinese artists. I also like to go to spaces for young/experimental/emerging artists. Magician Space is my pick today for its exhibition of works by the artist Liu Ding and poet Han Dong. Based on their longtime friendship, the show juxtaposes poems with images that interweave phrases of text. The works strike me as exemplary products Beijing’s artistic scene, with its circles of writers and artists who exchange reading material and experiment with intellectual cross-pollination.

Liu Ding, A Day, 2017, mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Magician Space

After seeing a few shows, I am ready for a cup of tea. I head to TeaHere, a teahouse that opened in the fall and is run by the artist Wang Guangle, gallerist Jiao Xueyang and curator Bao Dong. Entering it is like going to Kyoto: it’s obsessively Japanese in design. Their tea-for-two service is expensive, but they do have a 15 RMB iced tea. Installed around the small space are works by artists like Zhu Yu, Jiang Zhi and Liang Shuo – all of whom are “members” of the teahouse and come here to hang out.

Back in exhibition mode: it’s time for M WOODS and UCCA.

M WOODS was established by three young Chinese art collectors and opened in 2015. Its exhibition program thus far has brought works by exciting, big names from abroad, whose work would otherwise not be seen here. I’m waiting on the show of new media work by Chinese, European and American artists from founder Michael Huang’s collection, which opens at the end of June.

UCCA (the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art), located at the center of 798, is arguably the most influential institution of its kind in the country. In the past year, UCCA has mounted major exhibitions of works by William Kentridge and Robert Rauschenberg (figures familiar to MoMA and LACMA in the US). I choose UCCA to revisit its exhibition The New Normal, a group exhibition to survey the current landscape of contemporary Chinese art held once every four years. Unlike its precursors, this time a handful of the participating artists are not based in mainland China, giving it a much broader focus befitting of China’s increasingly globalizing society. My instant favorite is Sophia Al-Maria’s “Black Friday” (which I first saw at the Whitney Museum last summer);

Sophia Al-Maria, Black Friday, 2016, digital video projected vertically, color, sound, 16’36”. Courtesy of UCCA

Having worked up an appetite, I head to Timezone 8 for dinner. I see a handful of recognizable (some “famous,” ) curators and artists at the bar with Robert Bernell, the owner. Timezone 8 began as an art book publishing company in the mid-2000s that put out the most important catalogs at the time, before becoming a dual concept Japanese-American restaurant where the fish is incredibly fresh and happy hour drinks are 2-for-1.

With Black Bridge Art Village (Heiqiao) being destroyed and Caochangdi becoming quieter these days, the 798 Art Zone has once again been pushed to the forefront of Beijing’s art scene — one that, for the uninitiated, is one of the most exciting art scenes in the world.