Chinese Creative Revolution is an interview series initiated by Milo Chao profiling disruptive creatives working in China today.

“I don’t believe in communism or collectivism. I believe in the individual.” — Sci-fi author Hao Jingfang

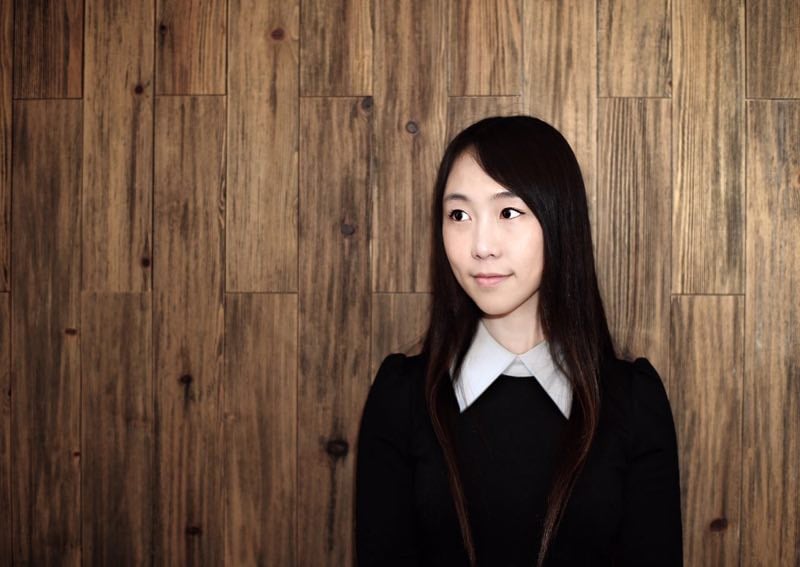

Hao Jingfang is the 2016 winner of the Hugo Award, science fiction’s top prize, for her novelette Folding Beijing (translated by Ken Liu). As just the second Chinese national to ever receive the prize – and the first woman – it propelled her to international fame, and made her a representative voice in her home country’s burgeoning science fiction scene.

Folding Beijing is set in a future Beijing divided into three time-space zones: First Space, for the elite minority, and Second Space and Third Space, for everyone else. The protagonist is a waste collector from Third Space who illegally travels above his grade as a messenger to earn quick cash.

Science fiction is said to be a mirror for contemporary society, addressing our anxieties. In 1978, China introduced a series of economic reforms that decollectivized agriculture, opened up the country to foreign investment and gave rise to private enterprise. The success of the reforms led to tumultuous social shifts, including economic disparity.

Hao, the only child of liberal-minded accounting professors, belongs to the first generation of Chinese born under “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” and has said it was her interest in social inequality that inspired her research. She exhibited talent early by winning writing awards throughout school, even as she was busy earning a doctorate in economics from Tsinghua University.

I meet her at a café in Beijing’s trendy Wudaoying Alley one afternoon in March. She wears black-stacked knee-high boots and a khaki trench, and looks more like a university student with a Korean fashion sense than a senior researcher at the China Development Research Foundation, her day job.

Hao orders her usual, a rose latte to go. She’s a fast walker who speaks in thoughtful, determined bursts. She is engaging, upbeat and efficient. When not at her office or home writing, she stays busy with multiple side projects. She is also the mother of a two-year-old. She wakes every morning around 4 or 5 am. “I sleep four to five hours,” she says.

In China, one is constantly reminded of William Gibson’s comment that the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed. In this sense, moving between different cities – and often, moving within the same city – can feel like time travel. As we walk out of Wudaoying onto the main road, it is as if we are departing First Space, with its third-wave coffee shops, wine bars and organic food restaurants, and entering Second Space, where generic office buildings line grand boulevards, a legacy of Cold War era alliances and Sino-Soviet friendship.

We settle in Hao’s office to talk about her projects, her faith, and the state of Chinese creativity.

PW: Do you think creativity comes from inside, or is it external?

HJF: Creativity must come from within. Personally, I think creativity is about being aware of your feelings at all times. Creativity is the process by which you express your feelings. Those feelings are formed through the intake of external information.

However, creativity is not a direct output, but the result of that information being processed, sometimes over a very long period of time. This process is creativity.

PW: What advice would you give someone about creativity?

HJF: In China, there are two common misperceptions regarding creativity. The first is that you must master something as a prerequisite to being creative, as if creativity is reserved for the masters and not novices. The second misconception is creativity is like a lightning bolt that strikes from the sky, or an apple that falls from a tree and knocks you on the head. It’s either something mystical or an inherent skill. Some even say young novelists must be reincarnated.

Creativity is either unattainable or mystical. The average person feels he or she has nothing to do with creativity and does not attempt it.

PW: Writing isn’t your full-time job. What are some of your other projects?

HJF: I have always had a personal interest in economics and economic history. These are things I do every day. I am also working on an education project with a friend regarding children’s creativity and a volunteer project to provide education to impoverished rural children.

We want to teach children that everyone has creativity within them. As long as you have a feeling and are able to convey that feeling, this is creativity.

We want to start with children because unlike adults, they are less self-defeating and inhibited. They make up games or stories to tell each other. We won’t offer too much criticism. Instead, we will say OK, we hear you, and encourage them to continue expressing themselves.

PW: What is your main motivation for initiating this project?

HJF: It’s purely personal. I am very interested in children’s education and psychology because I have a two-and-half year-old daughter. I have several friends with similar-aged children. We feel the public education system in China is too repressive, such as emphasizing one right answer. We wanted to create some extracurricular experiences that are more fun to encourage children and to say it’s OK to have a voice, we hear you, and the process of expressing it is creativity. We hope they can experience expressing themselves from a young age so when they grow older, they will be in a better position to create something more original.

PW: Do you think autonomy cultivates creativity in children?

HJF: Autonomy certainly won’t repress a child’s creative tendency. However, if I hadn’t received key praise and guidance later on, I might have become a person with an easygoing and happy outlook without the impulse to create something. A child may not necessarily know they have creativity within them.

PW: Western society is based on Christianity. Often, someone there will cite religion as a source of inspiration – faith in something greater leads to great accomplishments. Are you religious? How do you view the relationship between religion and creativity?

HJF: I’m an atheist. I believe the universe and its contents evolved on their own. Humans are individual life forms. The meaning of life and creativity are related to the universe.

I believe every person has it within them [to believe in something bigger than them], because I have it in me. I have faith in mankind. We don’t need something bigger than ourselves to be original.

I understand the concept of humility in Christianity. And it is good, to a degree, but I think it’s really unnecessary to place faith in something else other than people. I don’t believe in communism or collectivism, either. I believe in the individual. I think within this universe, every person has creativity within him or her. This is my faith. Every person has it in them.

Creativity is not about art, it’s about the individual and self-actualization. For instance, designing my office environment, arranging my workspace, this is what I mean when I refer to creativity. Creativity is self-initiative. In the Chinese creation myth, Nüwa blows on clay to create the first man, but for me, that breath of air was already within the person in the first place. Many psychologists such as Abraham Maslow endorse this humanist view.

PW: How would you describe the Chinese creative spirit?

HJF: In ancient times, there was the concept of the nobleman who had a sincere heart, cultivated moral character, and learned through experience. The nobleman then expresses himself through a poem, painting or perhaps song of the flute. As an official, these acts, rather than more practical skills such as accounting, would serve to validate his honor and qualification.

In ancient China, a specialized creative like a poet or artist was rare. The intellectual class wrote poetry, painted, served as officials and taught. Intellectuals were well-rounded individuals who synthesized the ideal traits for self-cultivation. Why was it like this? Creative output in ancient China was always linked to self-actualization.

It’s unlike in the West, where artists tend to pursue one skill to very high levels of mastery. Creativity may manifest itself in very technically advanced forms, at which point it becomes a skill to master, no longer human nature.

I don’t consider artistic creation a skill and technique. I don’t like to separate it from the person. I think the good thing about ancient Chinese artistic expression is people considered it to be a part of the nature of the mind.

The top artists have some things in common: they all create work based on life. If you think about the dancer Isadora [Duncan], she conveys her interpretation of life and emotions into her performance. This is an example of artistic creation not being severed from the person.

PW: What are your views on the future of Chinese creativity?

HJF: Creative forms will increase. Even now, I observe increasingly diverse, individualized and original creative output. Perhaps it starts with wanting to create something for you, and then slowly figuring out how to market it to a larger audience.

I have quite a few friends, including fashion designers, product designers and startup founders, who are all quite impressive.

Creativity is also related to security. When one is not very secure, the focus is on external needs. If I do this, I can rest; if I finish that, I can eat. Now that people have more time on their hands, naturally there will be more ideas floating around. Even if only some of those ideas are realized, that’s a start.

***

| Column archive |