On a sweltering Sunday morning, we’re at Shanghai’s Confucian Temple. It’s 8:30am, and the regulars have already been here for hours. But they’re not here for a sermon on filial piety — they’re here for lianhuanhua.

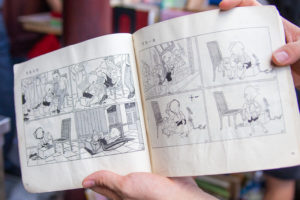

Lianhuanhua (literally translating to “linking picture book”) are China’s original comic book, dating back to the ‘20s. Small, rectangular, and built around one large picture per page plus accompanying text. Every Sunday, the Confucian Temple gives way to a bustling secondhand book market, where a consistent crowd of mostly older men flood in to read, trade, and participate in a fast-disappearing lianhuanhua culture.

A lianhuanhua featuring Sanmao, one of China’s most beloved fictional characters, who dates back to 1935

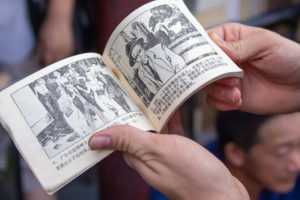

Western films, too, were reformatted and printed as lianhuanhua

“We’re all familiar with the ones from the ‘50s, but you could find lianhuanhua everywhere as early as the ‘20s,” one vendor named Wei told me. “I’ve read them since I was a child, back in ’56. I couldn’t read the words, but I thought the pictures were amazing, so I could understand the stories. Back then we didn’t consider these art — they were just comics. But today, many of those artists are quite famous. They have a different style than overseas cartoonists.”

The market itself spans all kinds of secondhand literature — from vintage photobooks, to old kung fu manuscripts, to ’90s Hong Kong porno mags — but looking around, most visitors are flipping through lianhuanhua and chatting with their vendors.

The comics themselves take on a myriad of different styles and subjects. There are serious, old school kung fu flicks. Ancient Chinese mythology. Cartoony, comedic shorts. Even classic Western films like Star Wars, re-illustrated, ported out, and ripped to the lianhuanhua format, long before bootleg DVDs (or DVDs themselves) existed.

I was pointed to a middle-aged man in shorts and a baseball cap as the resident lianhuanhua cultural expert. At his stall stacked high with tiny comic books, a few older men chimed in.

– “Lianhuanhua, it goes back to the ‘50s.”

– “No no, they had them in the Republic of China as well! Here’s a re-print of one of the original lianhuanhua. Just look at it — the drawings are excellent. Really stunning.”

– “Well, anyway, people collect them now. Anyone over 40 definitely read these when they were little. Now that we’re older, we really cherish the feeling they used to give us. So a few publishing houses have reissued new prints of some classic lianhuanhua, to recall that feeling from when we were kids.”

– “Just like you guys with Tintin! Same feeling!”

I didn’t like being generalized. But dammit, I love Tintin. I bought two bootlegged reprints of Land of Black Gold and Prisoners of the Sun and thanked them for their time.

Historically, lianhuanhua have seen ebbs and flows throughout changing times. Smatterings of comic-esque precedents date back as far as the 1880s, but the format achieved its first full swing in the ’20s when lithographic printing was introduced to China. At the time, China was still at a halfway point between literacy and illiteracy, and the picture-heavy books with simple text were perfectly positioned to catch on. Readers could pay a small fee to rent reading time at street kiosks, where vendors kept personal libraries and small stools for customers. Traditional stories from mythology and folklore were common subjects.

Later, lianhuanhua production dipped during the Cultural Revolution. Story themes shifted from folklore to revolutionary heroes and Maoist propaganda work. After that, in the ’70s and ’80s, lianhuanhua made a big comeback, and production saw a sharp increase. That’s where we get our Star Wars and our Tintins, but also a lot of our classic kung fu readables.

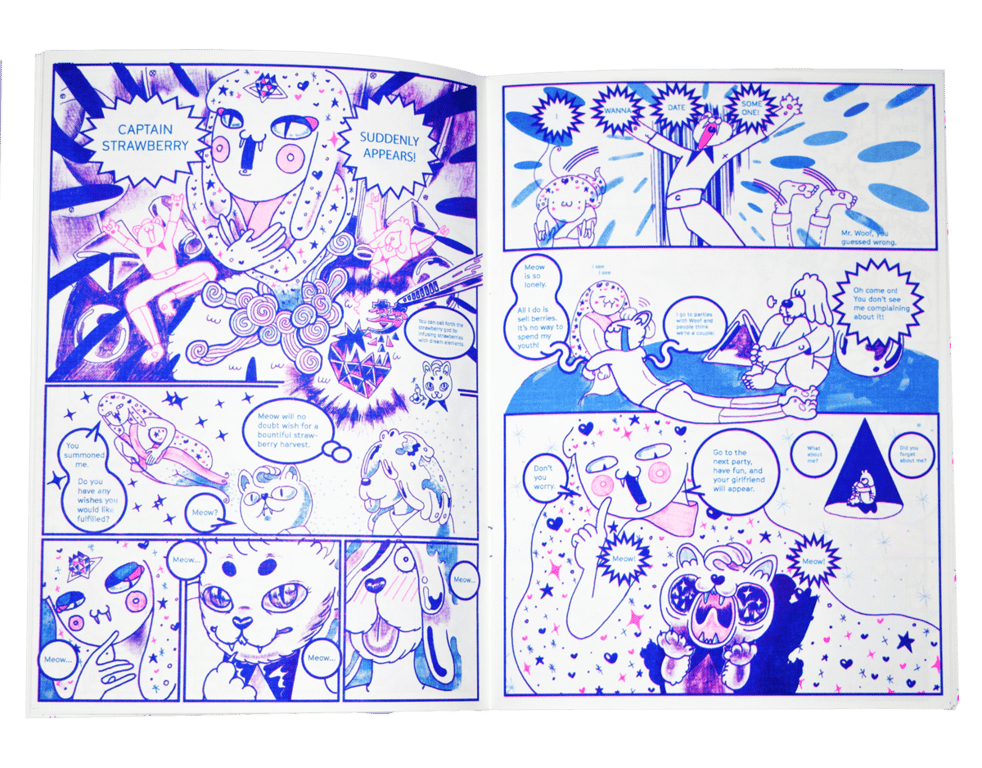

Today though, the modest comic books struggle to find an audience. Publishing houses offer reprints for dedicated fanbases and collectors, and the medium has achieved a level of recognition as fine art, appearing in exhibitions both in China and overseas (if Lichtenstein can do it, why can’t we?). Nonetheless, actual readership is, inevitably, shrinking. China’s youth prefer cartoons, or else Japanese manga — as evidenced by the shops selling manga-themed collectables along the street outside the temple.

Despite attempts to put a modern spin on the format by the likes of Paradise Systems, traditional lianhuanhua seem destined to drift quietly into the annals of history.

For now however, the passion of those who congregate weekly at Shanghai’s Confucian Temple shows no signs of dimming. “I loved them when I was a kid, so coming to this market, I still love them,” Wei told me. “I don’t have any other hobbies, and if you make something your hobby, you should be all in on that. This is my hobby.”

—

Images: Thanakrit Gu

You might also like:

Paradise Systems is Bringing the “Reality-Bending Features” of Chinese Comics OverseasArticle Aug 01, 2018

Paradise Systems is Bringing the “Reality-Bending Features” of Chinese Comics OverseasArticle Aug 01, 2018

“Playing Games with Taboo”: Tony Cheung on Art, China, and “Endless Physical Satisfaction”“Speaking about violence and sex, these are still a big taboo according to the authorities, or even mainstream values, which also lures me to break the limitation”Article Apr 26, 2018

“Playing Games with Taboo”: Tony Cheung on Art, China, and “Endless Physical Satisfaction”“Speaking about violence and sex, these are still a big taboo according to the authorities, or even mainstream values, which also lures me to break the limitation”Article Apr 26, 2018

“We are Visual Journalists”: Between the Lines of Beijing Comics Zine Hole in the WallArticle Jun 12, 2018

“We are Visual Journalists”: Between the Lines of Beijing Comics Zine Hole in the WallArticle Jun 12, 2018