If you’ve never been to Beijing but are keen to get a whiff of the gritty cultural vibes being brewed there, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better place to start than Hole in the Wall, a comics zine and art collective launched by Jinna Kaneko and Shuilam Wong last year. The duo met in high school in Beijing, though their paths before and after were complicated and circuitous, charting points through Tokyo, Hong Kong, Singapore, London, and San Francisco, among other places.

Illustrators by training, both Kaneko and Wong found themselves back in Beijing after college, and both have been sucked in by the vortex of eclectic creative energy coursing through the city today, especially its dusty inner-city alleyways, or hutong. The people they’ve met in the hutong, and the stories they’ve seen there, formed the inspirational basis for Hole in the Wall, an illustrated zine that profiles Beijing’s young, restless creative class, and is now on its third issue.

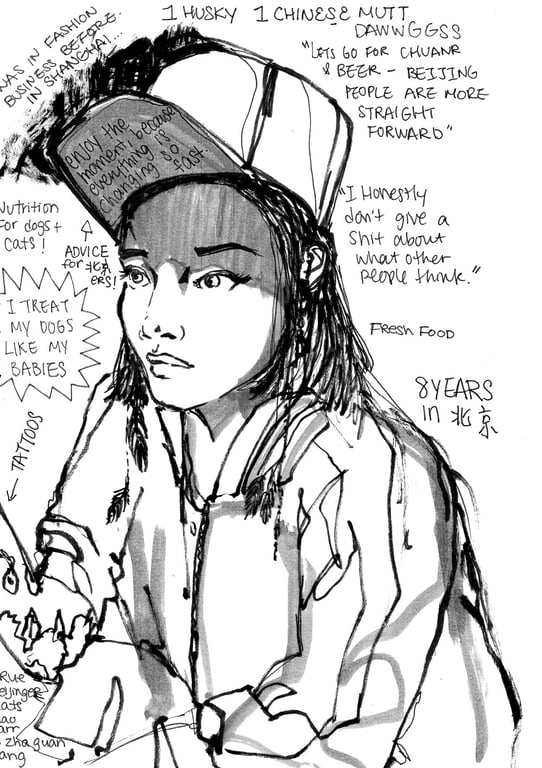

The founding duo behind Hole in the Wall have carved out a prominent place for themselves within Beijing’s creative scene, and have recently added more manpower to their cause in the form of 23-year-old Guangdong transplant Nigel (above), a designer who is now helping the collective expand their activities within China and across Asia.

We caught up with Jinna and Shui after a string of recent events across Beijing that have been keeping them busy, and have been feeding them new ideas to expand their vision across other locales and media.

RADII: First can you introduce yourselves? I understand that you both grew up between countries and cultures… Can you describe your background growing up?

Jinna: I was born in Tokyo, and was raised in Toronto and Beijing. My father is Japanese Korean, and my mother is Chinese. Growing up in Tokyo was odd for me because my father owned many pachinkos and was in real estate in Japan. My mother was a housewife. I was raised in a very luxurious lifestyle, and then the Japanese economy crashing started affecting our family. My mother took the kids — two other siblings and I — to Toronto, and we lived very minimally. After four years, she was deported from Canada, and a year after she left, we joined her in Beijing. Beijing was a very interesting experience for my teenage years, because everything was so free. Everything I learned growing up was validated here, even if it was something corrupt. Being so free, I learned a lot about negative actions and the consequences attached to it.

Jinna

Shui: My parents are from Hong Kong and work for a multinational corporate firm, so they moved around often. I was born in Japan and grew up in Singapore and Beijing before going to London for university. I also visit family in Hong Kong a few times a year, and have always found the city simultaneously familiar and foreign. As a child I encountered many cultural shocks and conflicts. I was bullied in kindergarten when we first moved to Singapore from Japan — I could only speak Japanese and Cantonese at the time, so the kids couldn’t understand and refused to play with me. Teachers wouldn’t let me use Japanese, so I eventually lost that language.

When I finally became accustomed to and deeply influenced by Singaporean culture, we relocated to Beijing and had to start over again. But going to international school and living in a completely foreign environment definitely shaped my confidence and open-mindedness.

Shui

What are your backgrounds in art and illustration? What are your day jobs?

Jinna: Shui and I actually went to the same high school in Beijing, and we had art classes together. I went on to study illustration at the California College of the Arts, and she went to London to study the same thing. I work as a visual designer at Yuecheng Technology, a VR-related company, and freelance illustration and graphic design.

Shui: I studied illustration at Camberwell College of Arts in London. It was the perfect balance between conceptual fine art and communicative design. During that time I also worked part-time as a graphic designer in a small Japanese cosmetics store in Chinatown. The boss liked my drawings and decided to let me do posters, business cards, and flyers. I learned everything about design on the job and through looking up how-to instructions. Now I work full-time as an in-house graphic designer during the day to sustain my Illustration works.

Given that you both grew up all over the place, what brought you back to Beijing this time around? What keeps you here?

Jinna: I had a lot of negative energy when I went to Paris for a year after university. I realized then [that] it would be best if I came back “home” to Beijing. My family, friends, and the tight art community keeps me in Beijing. WeChat groups changed my life.

Shui: To be honest, I never thought I’d be back. After high school I just wanted to get out, because I thought everything cool was happening overseas. A year after graduating from university, I randomly stumbled upon a job here while visiting my father. I decided to stay, because I was unemployed at the time and tired of London.

The tight-knit creative community is what keeps me here. Beijing has a very global-minded and welcoming group of people that I couldn’t find in London. There are artists, musicians, poets, writers, and entrepreneurs chasing their dreams and helping each other out. This sense of possibility and energy has made me decide to stay longer than intended.

Do you think your nomadic childhood influences how you interact with Beijing today? Has it shaped the perspective that you’re trying to get across with Hole in the Wall?

Jinna: I associate each city with a story, and I became obsessed with history and stories. Hole in the Wall is a way to document stories, people’s reactions to things that are changing around them, and different kinds of subcultures.

Shui: Certainly. Growing up internationally has helped me look at this quirky city with better understanding and a more objective perspective. Instead of forcing Western or foreign logic on Beijing, I accept it for the way it is. As someone who has always been an outsider, I’m able to adapt to my surroundings and have better awareness of what’s going on. With Hole in the Wall, it’s an outsider looking into Beijing through insider lenses. Our portrayal of the underground scene may be of more expats than locals, but that’s just because these happen to be the people we have encountered.

I’m interested in your approach with Hole in the Wall, as it’s semi-anthropological, based on interviews and real-life stories, yet framed in a format that is typically associated with fiction. What is your concept here?

Jinna: We are visual journalists. Our zines are filled with illustrations and dialogues of people we meet. We draw them in real life while asking them questions. We found that by using interviews and real life drawing, we could get closer to the people we would be nervous talking to in the first place, and we ended up connecting to them on a deeper level. We also formatted the zines in different issues covering specific Beijing underground themes and changes.

Shui: Hole in the Wall zine started out as a creative outlet for us. When we reunited, we had stopped creating illustrations since university, and were craving a project. Beijing, specifically the people, was our main inspiration, so we wanted to talk to young people from different cultures. The idea was to sketch interviewees while getting to know them. During our first interview, Jinna’s phone died and my computer refused to record sound, so we ended up writing everything down. The combination of portrait illustration and handwritten stories became the format of our zines. There’s something very raw about using illustrations — it’s very hands-on and spontaneous. We can focus on certain parts of the subject and omit the rest.

Can you share one or two of the more interesting stories you’ve drawn out in your interviews?

Jinna: My favorite interview is probably Oliver, lead singer of a band called Struggle Session. We asked him about his reactions towards demolitions and evictions in the hutong. His experience with this was that there were a few studios that had to move because of the demolitions, but they persevered, and ended up having more benefits than they could have if they stayed in the same spot. He reminded me that each change can be viewed positively, and sometimes change is important for growth.

Shui: I suppose our first ever interview resonates with me the most — we had no idea what we were doing, and were incredibly late. We interviewed Tao, a badass chick who cares so much about animals’ health and nutrition that she opened an independent F&B business to provide fresh food for dogs and cats. It’s such a niche thing to do, but she loves it and is doing a great job. She also has really sick tattoos, and this amazing attitude of following her heart.

Your second issue was themed around bars and music, and your third was subtitled “Beyond the 拆,” referring to the hutong demolitions and evictions you mention above. How did you land on these themes? What other themes do you have planned for the zine?

Jinna: We started hanging out in the hutong more often when we came back to Beijing, experiencing the expat community, bars and restaurants, and we realized that the demolitions were happening again. When we went to school in 2008, many villages were demolished for new infrastructure for the Beijing Olympics. So we realized we needed to record everything before and after the demolitions. When we explored these themes, we became drawn to Beijing underground culture — musicians, DJs, and artists who lived in this area. We want to keep on exploring these underground artistic themes, so we’re planning to record art and technology, DJs, musicians, performance arts, poetry, and dance in Beijing, Shanghai, Tokyo, and Hong Kong.

Beijing hutong scene

Shui: Our themes really depend on whatever is happening in our lives at the time. Before the second issue, we were hanging out in bars and live houses a lot. Once on the subway, we talked about making a zine about Beijing nightlife — we’d stay up one night and just draw whatever happens and wherever we end up. A couple weeks later that’s exactly what we did for the “Bars and Music” issue. The third issue was created around the same time many of our favorite places were destroyed. Sanlitun bar street was a vital part of our high school memories, as we spent nights getting drunk on fake alcohol.

Our next issue will be on the theme of performance. Besides live music, there are also many other forms of underground shows, such as slam poetry, art performances, and dance. We hope to feature a variety of such entertainers in Beijing. We also have ideas of making cross-city zines, whereby we record the underground culture in other East Asian cities such as Tokyo, Hong Kong, Seoul, and Taipei.

Jinna — I’ve read that you’re working on a graphic novel “that explains, through personal experiences, post WWII in Korea, China and Japan.” What is the status of that? What are your personal stories connected to this fraught topic, still a source of tension between the three countries today?

Jinna: The first chapter of my graphic novel is in Spittoon comics, which will be published soon. I’m still working on the graphic novel, and might be able to finish it in the next two years. Because my father is Korean Japanese, and my mother is Chinese, my grandparents and parents had many interesting stories during WWII and after. Growing up in Beijing, I had many friends that also experienced the troubles during the anti-corruption campaign in 2014, and all these experiences and struggles repeat in each generation. I want to express the struggles and understanding of history to get to the point we are at today, to let people understand why our generation is like this.

Shui — What are you working on outside of Hole in the Wall?

Shui: I’ve been working on a comic that’s inspired by Hong Kong and my grandfather. He’s 83 and one of the coolest guys I know, smoking from a pipe, carrying a black waist bag, wearing Ray Bans and practicing Wing Chun in the mornings. The story is fictional, but the character is entirely based on him. Recently I’ve become really interested in ’70s Hong Kong, and went through old photos of my family. My mum had such cool style with large permed hair, bold eyebrows and a mysterious smile. I’m hoping to do more illustrations based on this, and perhaps make a zine.

Anything else you want to add?

Shui: We want to expand Hole in the Wall, focusing more on online content and merchandise, along with the zines and murals. That’s why Nigel joined our team, to help with social media, translations, and to provide general assistance. We want to reach out to more people and become a platform for underground scenes across East Asia. That’s just a really big dream of mine, but for now we’ll be doing illustrations and interviewing cool strangers we meet.

—

All images courtesy Hole in the Wall

You might also like:

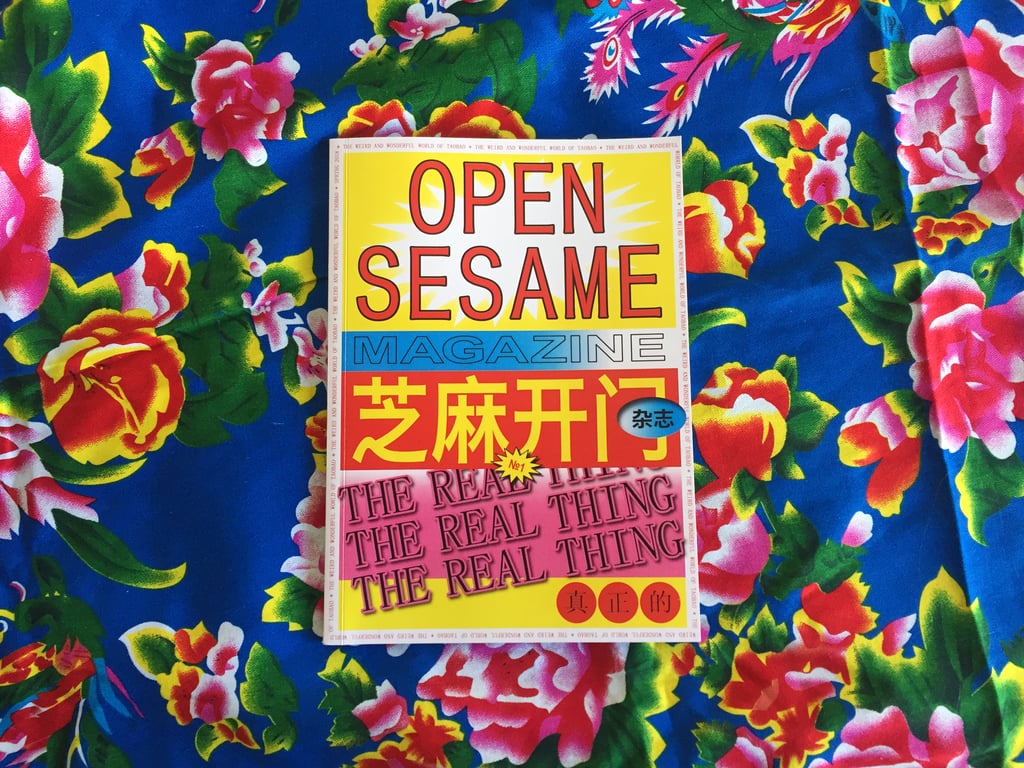

Open Sesame Magazine is Curating “Weird Taobao”Article May 24, 2018

Open Sesame Magazine is Curating “Weird Taobao”Article May 24, 2018

“Playing Games with Taboo”: Tony Cheung on Art, China, and “Endless Physical Satisfaction”“Speaking about violence and sex, these are still a big taboo according to the authorities, or even mainstream values, which also lures me to break the limitation”Article Apr 26, 2018

“Playing Games with Taboo”: Tony Cheung on Art, China, and “Endless Physical Satisfaction”“Speaking about violence and sex, these are still a big taboo according to the authorities, or even mainstream values, which also lures me to break the limitation”Article Apr 26, 2018

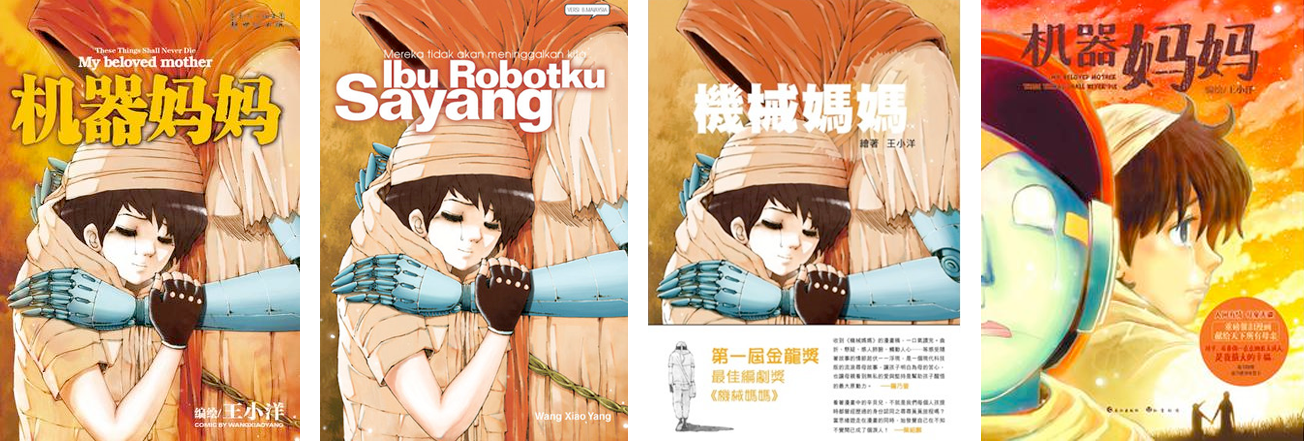

My Beloved Mother: A Comic Book Epic About Human-Android DiscriminationArticle Dec 09, 2017

My Beloved Mother: A Comic Book Epic About Human-Android DiscriminationArticle Dec 09, 2017