The State Council — China’s chief administrative body — surprised Chinese parents and for-profit tutoring centers alike last month when it announced sweeping changes to the private tutoring and curriculum-based training center industry. The goal: reduce students’ workloads and tighten rules on for-profit curriculum tutoring companies.

In the wake of the announcement, much ink has been spilled on the economic impact of the regulatory changes, job losses experienced by foreign employees at affected businesses, and the role China’s chicken parents have played in growing the industry.

Less space, however, has been dedicated to how familial and societal pressures have impacted students’ education experience and led many of them into a seemingly never-ending cycle of after-school educational programs.

In parts one and two of our three-part series on China’s reform of the for-profit curriculum-based tutoring industry, we introduced the phenomena of chicken parenting, how training centers lure parents and how some parents have come to rely on after-school programs. In our final story, we look at how China’s high-pressure education environment impacts families and educators.

Big Shoes to Fill

In May, the hashtag #PKU prof can’t help his daughter with homework# went viral on Weibo, receiving more than 470 million total views. The hashtag was created under a video of Professor Ding Yanqing from Peking University School of Education discussing his struggles parenting his daughter.

Ding himself was a child prodigy, and both he and his wife graduated from Peking University, one of China’s top two universities. Ding’s daughter, however, used to receive the lowest grades in her class, and when Ding tried to help her with schoolwork, he and his daughter would “transform from the best dad-daughter duo to a state of war.”

Professor Ding Yanqing from Peking University School of Education discussing his daughter’s academic struggles. Screengrab via Weibo

His daughter’s grades did improve, but then she began to worry about not being close enough to the top of her class.

Eventually, Ding came to terms with the fact that his daughter would not be as achieved as he is. “She’ll be an average person, and it’s okay. What I do care about is her happiness.”

Another hashtag that went viral alongside Ding’s video: #Will you be okay if your kids won’t be as accomplished as you are?#. According to two surveys by Wuxi TV and China Youth Daily, about 30% of the participants cannot accept their kids achieving less than they have.

Of this 30% of Chinese parents, many become chicken parents (parents who do everything in their power to make their kids perfect), and a lot of chicken parents share similar personal backgrounds. M, a teacher and manager at a private tutoring company in China who asked to remain anonymous, identifies the chicken parents he has met as “those who achieved what they achieved because of how hard they worked.”

Related:

China’s Embattled For-Profit Tutoring Sector is Fueled by Anxious ParentsChina’s new education reforms aim to free students from chronic academic stress, but some parents are likely less than thrilled with the changesArticle Aug 10, 2021

China’s Embattled For-Profit Tutoring Sector is Fueled by Anxious ParentsChina’s new education reforms aim to free students from chronic academic stress, but some parents are likely less than thrilled with the changesArticle Aug 10, 2021

A lot of these parents did not grow up in the city they now live in. For them, education was what brought them out of poor rural villages, gave them their current job and social status, and planted their roots in the fastest-growing cities of one of the world’s fastest-growing countries.

These chicken parents want for-profit training centers to exist because they are too busy to care for their children and because they can afford the most expensive cram schools to offer their kids a competitive edge. More importantly, they fear losing their socioeconomic status and view tutoring as a way to ensure their children don’t tumble down the ladder.

“You have learned through your own experience how you can change your fate and ascend through the socioeconomic ladder by working hard,” M says, reflecting on his interactions with these parents. “So, when it’s your turn to parent your kids, you will hold the same expectation for them as well.”

Whether chicken parents’ preconceived path for success still works today is up for debate. In 2020, the newly-invented phrases ’Small-town Test-taking Specialists’ (小镇做题家) and ‘Top-college Garbage’ (985废物) went viral on Chinese social media. The terms refer to now-grown chicken children who graduated from top colleges and cannot find a satisfying job.

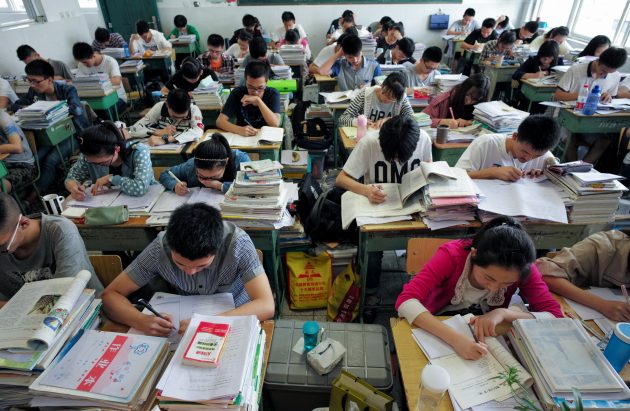

Chinese students review textbooks in preparation for China’s national college entrance exam. Image via Depositphotos

These graduates went to the most intense high schools and participated in extracurricular activities or after-school tutoring, firmly believing that going to a top college would guarantee their future success. However, as the number of Chinese college graduates has drastically inflated, their efforts were futile.

The younger generation is deconstructing the narrative of using hard work to alter their fate, but not the older generation. When the government announced its crackdown on for-profit tutoring centers, some chicken parents in WeChat groups reacted with confusion and anger.

“Are you kidding me? I’m not sending my kid to a vocational school,” stated one parent. Another parent, who detests the idea of lowering expectations for his child, wrote:

“If a parent is a policeman, having seen so many people serving life sentences, should he be happy as long as his kid doesn’t end up in jail?”

However anxious these chicken parents are, people in the education industry do not think the cram school industry will vanish. M, for example, sees no reason for parents to worry.

“The education companies know that there is a demand for their product. They will do anything to produce something that will satisfy the parents,” says M. “The companies want to stay afloat, so they will be the ones working to allow the parents to send their kids somewhere.”

Other insiders believe that big educational brands may perish, and individual tutors will dominate the industry in the future.

Industry insiders are split on whether or not China’s for-profit tutoring companies will survive the current government crackdown. Image via Depositphotos

“The most enthusiastic chicken parents will always find a way to chicken their kids,” says K, a 15-year veteran of the education industry who requested anonymity. “The cram schools can be shut down. The parents will find a few other parents, rent a room in an office building, and find a former cram-school teacher. Now, they become the boss of their own ‘cram school’… the only downside is that they’ll be paying a bit more.”

“But for the parents committed to chickening their kids,” K adds, “do you think they’ll care?”

Relationships vs. Transactions

“The educational reform ought to … reduce homework, decrease the emphasis on tests and examinations, and support schools’ effort to teach students how to be humans.”

— Xinhua

Z is a graduate of one of China’s top colleges and has been a teacher at a public high school for more than 30 years (and, like so many others we spoke with while compiling this story, wanted to remain unnamed). Upon finishing college, he became a teacher because he had always adored the bond between teachers and students.

When he first became a teacher in the ’90s, he was promptly rewarded with students he got to know very well and remained friends with after they graduated. However, he feels that it has become increasingly challenging to bond with his students in recent years.

Related:

Chinese Parents’ Complicated Relationship with After-School TutoringHere’s how China’s training centers lure parents in and how some parents have come to rely on after-school education programsArticle Aug 13, 2021

Chinese Parents’ Complicated Relationship with After-School TutoringHere’s how China’s training centers lure parents in and how some parents have come to rely on after-school education programsArticle Aug 13, 2021

“The teacher-student relationship has become more transactional,” says Z. “There’s only one metric of evaluation: whether I have succeeded helping my students improve their test scores.”

He understands that this excessive emphasis on score results comes from the increasing competitiveness of the gaokao — China’s standardized college entrance exam. But he still feels deeply dissatisfied with how students and their parents have changed as humans.

Chinese mothers hold up sunflowers to wish good luck to their children sitting the national college entrance exam, also known as the gaokao, in front of an exam site in Chengdu, Southwest China’s Sichuan province, on June 7, 2018. Image via Depositphotos

“There was one time over the weekend that a student had some questions about an exam review worksheet and texted me the questions early in the morning,” says Z. “I saw the text, but I was busy with something else. So, I didn’t respond to her.”

Two hours later, Z finished up his business and responded to the student. A while later, the student responded with a few follow-up questions, and he answered them all. Later that day, the student suddenly asked, “Can you tell me why it took you so long to respond to my questions?”

Z was caught off-guard. “First of all,” he says, “It was a weekend. I expect my students, who were already in high school, to know that they should not bother people during their days off and that I had no obligation to respond to her. This is basic courtesy.”

But Z was not in the mood to give his student a lesson on etiquette. So instead, he scrolled through the chat history and calculated the number of times the student waited for him to respond and the number of times he waited for her to respond.

It turned out that between the two of them, the student was worse at responding to texts.

Chinese student Zhang Yiwen poses for photos while doing sample tests after finishing the first day of the national college entrance exam, also known as the gaokao, in Shangqiu city, Central China’s Henan province, on June 7, 2016. Image via Depositphotos

“Parents do similar things, too,” Z says, recalling when a mother angrily asked him why he did not pick up a call from her at 11 PM the previous night.

“It may be a result of students taking too many private lessons,” Z suggests, “where they pay for a service and get to complain when the service is unsatisfactory. But I’m a teacher, and I’m a human, and humans should treat each other like humans. Is this too much to ask for?”

In the modern era, relations between teachers and students are taking a new form, as are interactions between pupils themselves — even primary school students.

D is a mother of two daughters and requested to remain anonymous for this story. She recalls that one evening when she asked her daughter about her day, her daughter told her that one of her peers asked everyone their final exam scores and recorded the scores in a notebook.

“Kids have begun worrying about how they can or cannot beat their peers academically already,” D laments, adding that her daughter was only in third grade at that time.

Such pressure on students can have devastating and irreversible results.

China reportedly has the highest youth suicidal rate in the world. Image via Depositphotos

Kelly Zhou, the head of a Shanghai-based private international kindergarten, attends regular meetings with local governmental administrators. “In every meeting, the first item on the agenda is always to report how many new youth suicide cases there have been since the last meeting,” says Zhou.

According to data from The Economist, China reports the highest youth suicidal rate in the world.

But there is reason to be optimistic: If the State Council’s new rules on for-profit curriculum tutoring companies can even slightly reduce the academic burden on youth, then the regulations are a positive development. And suppose China’s public schools can integrate training centers’ positive aspects, such as after-school childcare services. In that case, it’s fair to assume many parents will be able to stomach the regulatory changes.

Among those interviewed for this series by RADII, nobody believed that after-school tutoring was inherently bad or that it should be abolished entirely. In the words of one teacher we spoke with, “If some elements of the private education institutions are incorporated into the public school system, then kids, parents and educators will be able to benefit from it.”

Cover image via Depositphotos