If you don’t live in China or follow startup news, the phrase “dockless bike share” might need some explanation. If you do live in China, you pretty much can’t not know what it is at this point. In less than a year, dockless bike share has moved from a novelty mode of transportation to an inescapable part of the daily commute in virtually every major Chinese city.

Here’s how it works: you walk up to a bike, whip out your phone, open your bike-share app of choice, and scan a QR code (these are far more prevalent in China than the West, but that’s a topic for another day). At this point either your bike unlocks automatically, or you receive a four-digit code to manually unlock it. Ride it to wherever you’re going, and lock it up when you’re done. That’s it.

This might not sound like an amazingly revolutionary technology. Public bike share programs aren’t new; Paris’ Vélib’ system, to take a prominent example, has been around for a decade, but requires users to pick up and drop off their wheels at designated docks. The Beijing municipal government has had a docked bike share system in place since 2012, as have many other cities around China. You can still find docks full of red bicycles all over Beijing, but they already feel like a quaint relic from a distant past.

On today’s streets, they’ve largely been replaced by two major private-sector players: Ofo, aka “the yellow one,” which was founded in 2014, making it the first dockless bike share company; and Mobike, “the orange one,” which was founded in early 2015. Both raised serious capital in 2016, and have expanded dramatically across China this year. There have been many other fast followers (e.g. Bluegogo if that’s your color, Cool Qi if you’re into conspicuous consumption), but Mobike and Ofo rule the roost, and are in a dead heat to establish bike-share supremacy. Both have plans to expand to 200 cities internationally by the end of 2017, and both have recently racked up huge investments to get there. Mobike raised $600 million in their latest investment round in June, and Ofo, not to be outdone, clocked $700 million earlier this month.

This battle of the bike-shares can also be seen as a behind-the-scenes proxy war for dominance between two of China’s largest internet companies. Mobike’s recent investment round was led by Tencent, creator of ubiquitous social messaging app WeChat, and Ofo’s by Alibaba, maker of, among other things, the massively distributed Taobao online marketplace (think eBay x Amazon for China’s 668 million internet users). These two titans are also squaring off in other sectors, such as mobile payments (a topic for a future explainer). Dockless bike share, as an instantly mass-adopted but still brand-new Internet of Things technology, will likely prove a fertile field of innovation for Tencent and Alibaba’s ongoing competitive scrum.

Corporate rivalries aside, dockless bike share in general is a win-win-win technology: good for the user, good for the city, good for the environment. In a white paper released in April, Mobike claims that “bike sharing has more than doubled the usages of bicycles in China.” A user group surveyed by Mobike claimed a 55% decrease in car trips and a 53% decrease in use of motorized rickshaws. 20% say that they use share bikes to connect with public transportation nodes as part of a longer commute. While Mobike is certainly biased in reporting the merits of its own product, the sheer density of shared bikes on the street today suggests huge potential upsides for CO2 reduction and public health, as more Chinese ditch taxis to cycle.

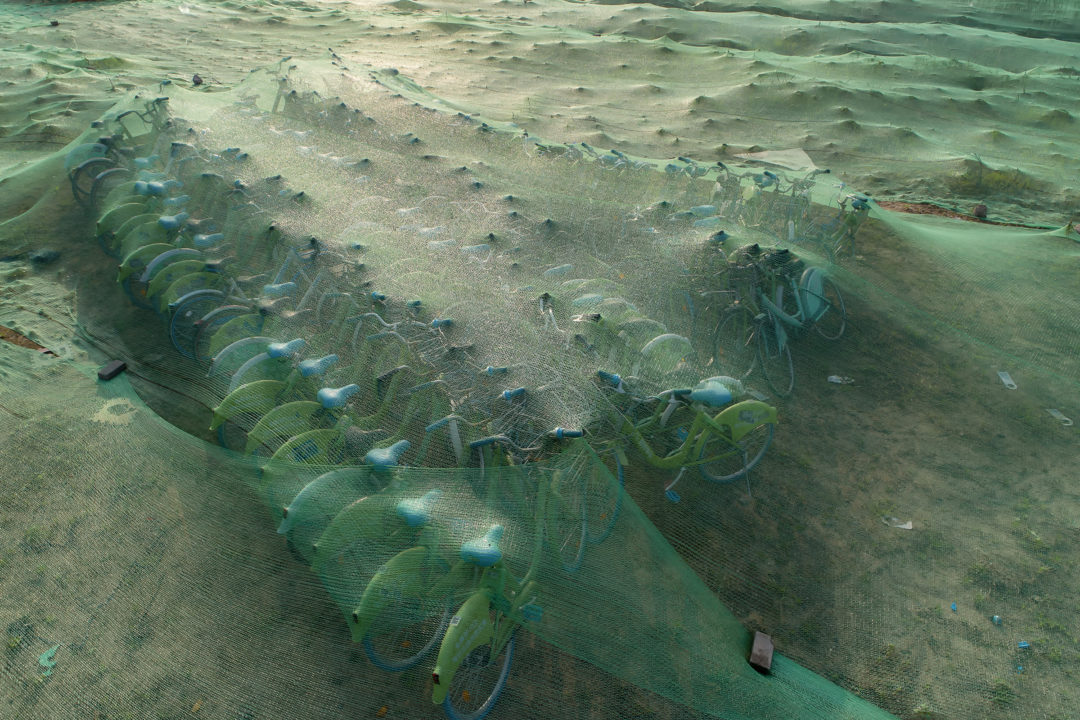

There are also downsides, of course. All those bikes have to be parked somewhere when they’re not hosting a rider, and they tend to stack up in ugly piles, especially near major subway or bus stations. Share bikes choking pedestrian sidewalks have angered people who won’t or can’t use the technology themselves, like the visually impaired. Fleets of identical bikes in a handful of colors don’t do much to counter the stereotype of China as a sea of cultural conformity. And then there’s the dockless bike share business model.

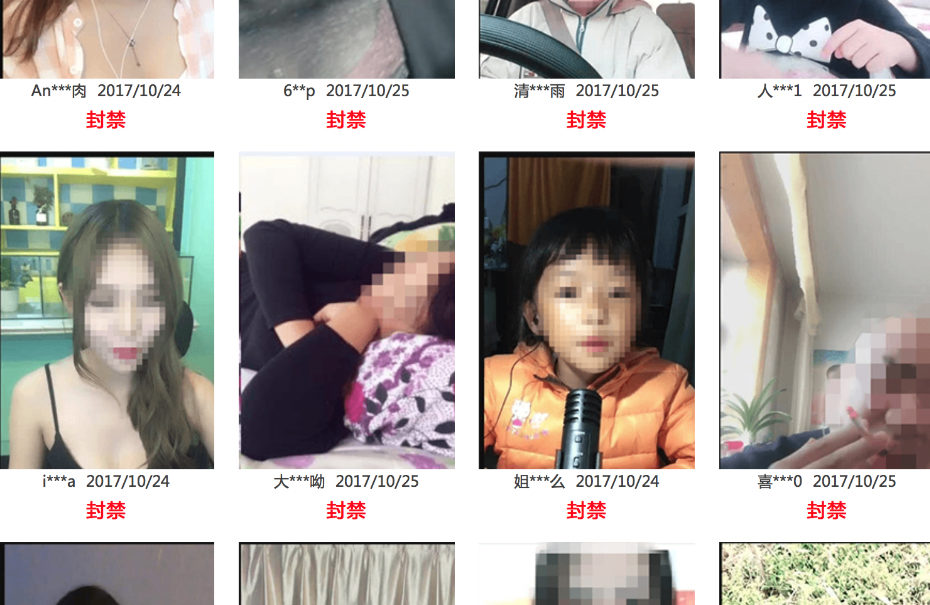

At the moment, there doesn’t seem to be one. Mobike and Ofo both require a deposit to begin using their services (around $40), but individual rides max out at 15¢ per half hour, and in their battle for market share both providers regularly offer free rides, and sometimes even cash-back virtual hongbao (red envelopes of cash given to friends and family at holidays, which have also made their way into smartphone culture).

So, companies like Mobike and Ofo are basically burning through this deposit money — which can be reclaimed by the user whenever they want to quit the service — and their investment stockpiles until they figure out how to capitalize on their service without radically raising prices. Their ultimate product might not be bikes, but information. Mobike recently announced a spinoff product, Magic Cube, an artificial intelligence platform built to divine useful patterns from the immense crush of data generated by all those sensors in all those smartphones on all those (100 million) Mobike users. The obvious application here would be to sell this information to municipal planners to optimize traffic flow, which doesn’t sound terrible in theory, but many might bristle at the idea of all of this freely shared location data being sold to government bodies.

The near-instantaneous, mass adoption of dockless bike share around China means that the technology will be hard to predict moving forward. For every article touting Mobike and Ofo and their ilk as the next big thing, there’s a Cassandra somewhere claiming that they’re about to go bust, or that their ultimate ability to generate revenue is a myth. In any case, Mobike and Ofo have a lot of new money to burn through, and in addition to battling for China market share, both are casting their gaze overseas: Mobike recently deployed fleets in Manchester and Singapore, and Ofo launched trial operations in Cambridge and Silicon Valley earlier this year.

The concept of dockless bike share looks poised to spread throughout the US as well. Beijing company Bluegogo has had halting success in San Francisco. Homegrown startups in progressive hubs like Seattle and Austin are attempting to introduce the technology to urban commuters. Whether domestic competition can head off the massive scale and technological advantages of the heavyweights Ofo and Mobike remains to be seen.

Either way, dockless bike share is an instructive example of a technology invented, iterated, and perfected in China before most people in the West had even heard of it. This is a phenomenon that I believe we’ll see a lot more of as China’s innovation engines churn out the next wave of future tech.