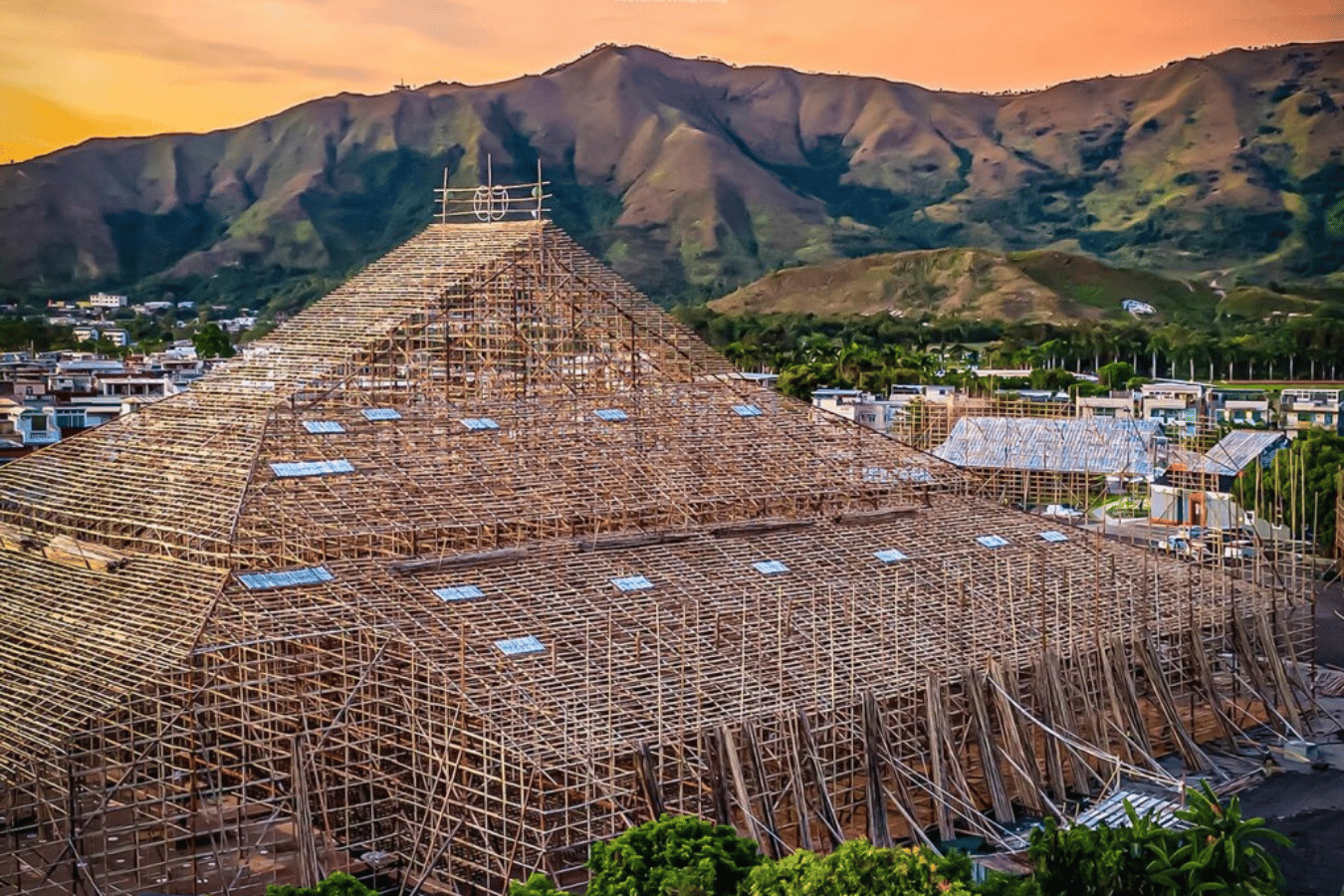

Hong Kong‘s Kam Tin Village in Yuen Long, a towering bamboo structure has quietly entered the history books. The newly completed altar has been recognized by Guinness World Records as the world’s largest temporary bamboo altar, an achievement rooted as much in tradition as in sheer scale.

The structure is no ordinary scaffold. Rising five stories high, the bamboo pavilion anchors the Kam Tin Heung Jiao Festival, a ritual event that takes place only once every decade. This year’s festival runs from December 13 to 19 and marks its 34th edition, continuing a centuries-old tradition overseen by the Tang clan, one of the New Territories’ most prominent lineages.

Built entirely from bamboo, the altar covers 3,897.409 square meters, or just under 42,000 square feet. It is a feat of craftsmanship that reflects not only technical skill but also collective effort. The price tag, reportedly around 20 million HKD, underscores how seriously the community takes the responsibility of maintaining this heritage.

The Kam Tin Jiao Festival, also known as Taiping Qingjiao, dates back to 1685. It began during the Qing dynasty as a Taoist thanksgiving ritual intended to bring peace and protection to the village. The festival commemorates a period of forced evacuation near the border, honoring both the officials who later permitted villagers to return and those who died during the upheaval.

While the record-setting altar has drawn international attention, the festival itself remains deeply local in spirit. Over the course of the week, Kam Tin fills with lion dances, Taoist rites, vegetarian banquets, and Cantonese opera performances. These elements are not staged for spectacle but serve as living expressions of walled-village identity that have been passed down for generations.

What makes the Kam Tin Jiao Festival remarkable is not just its scale or rarity, but its continuity. In an era when traditions are often compressed into tourist-friendly displays, this event remains rooted in communal memory and obligation. The bamboo altar may only stand for a short time, but the values it represents have endured for more than three centuries.

Cover image via The Standard.