If you think Facebook has had a tough two years — as it faced a reckoning of the consequences of its technology in the U.S., Europe and countries across the world — you aren’t wrong. But Facebook is hardly alone.

China is now home to the world’s most valuable start-up and has several other internet giants to compete with Silicon Valley’s. But just like Silicon Valley, 2018 was a year where Chinese companies saw their products and technologies come up hard against the real world. The struggles were something of a wake-up call for China’s tech giants as they attempt to go out into the world.

This was perhaps most evident in the stories that made global headlines such as the arrest of Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou or in Bloomberg‘s controversial story on the Supermicro “big hack”. But here are some of this year’s other major stories in Chinese tech, which suggest that 2019 will be far from plain sailing for some of the country’s biggest companies.

Short-Sighted Gaming Policies

A gamer trying on a HTC head set at China Joy 2018 in Shanghai.

China’s Ministry of Education announced in August that it would implement new restrictions on the number of new online games to reduce myopia in the children, hitting the businesses of Chinese game makers.

The restrictions (link in Chinese) require the publishing regulator to control the total number of games, limit the number of new games, explore an age-appropriate ratings system, and find ways to limit the amount of time spent online by minors.

Tencent, the country’s largest gaming company (which also owns WeChat, the widely used messaging platform), lost 20 billion USD in value on the market immediately after the announcement, according to Reuters. This added to the battering that shares had taken earlier in the year when it emerged that the approval of all new games had been frozen while the government assessed its options.

Related:

Rumors Swirl of Tencent Removing “PUBG” Titles Amid CrackdownArticle Sep 20, 2018

Rumors Swirl of Tencent Removing “PUBG” Titles Amid CrackdownArticle Sep 20, 2018

Myopia or nearsightedness is considered to be a serious issue by those at the very top in China. Leader Xi Jinping has made the focus on eyesight clear, saying in August that, “All of society must take action to protect children’s eyesight to allow them to have a bright and clear future.”

One reason vision is seen as so important is down to recruitment for the military suffering because, officials say, recruits do not meet physical requirements. Or if you want to think about this in a more humanist way, in the words of the Ministry of Education, “Children are the future of the country and the hope of the people”

Related:

China Forms Online Gaming Ethics Commission, “Rectifies” 11 TitlesArticle Dec 12, 2018

China Forms Online Gaming Ethics Commission, “Rectifies” 11 TitlesArticle Dec 12, 2018

Delete Didi?

Didi Chuxing, China’s version of Uber, has been in apology and self-reflection mode throughout 2018 after two of its drivers murdered passengers.

In May, a Didi driver stabbed and killed a 21-year old flight attendant. Three months later, another Didi driver raped and killed a 20-year old woman. Both were passengers on Didi’s carpooling service, Hitch, which had already been forced into a number of changes regarding passenger safety.

Chinese netizens widely criticized Didi for its apparent lack of urgency in responding to customer complaints, especially concerning safety. Local media reports had revealed that a customer had called to complain about the second driver just one day prior.

Related:

China Explained: The Rise, Fall, and Uncertainty of Didi’s Ride-Hailing DynastyArticle Nov 15, 2018

China Explained: The Rise, Fall, and Uncertainty of Didi’s Ride-Hailing DynastyArticle Nov 15, 2018

After the second murder, Didi took the service offline for two weeks and fired two executives. After two weeks, it added a new panic button to its app that is directly linked to the police and asked users to set up emergency contacts. It also added more stringent requirements for drivers who pick up passengers at night.

But the apologizing has continued. In October, Didi executives held a public comment session which they ended by saying there were many more areas where Didi can improve. The company’s CEO, Cheng Wei asked the public (link in Chinese) to critique Didi with the “most severe” gaze and help the company.

Nevertheless, as we head into 2019 and as a number of rivals to Didi emerge, there remain doubts over whether the months-long apology tour will be enough.

The End of the Bike Sharing Boom

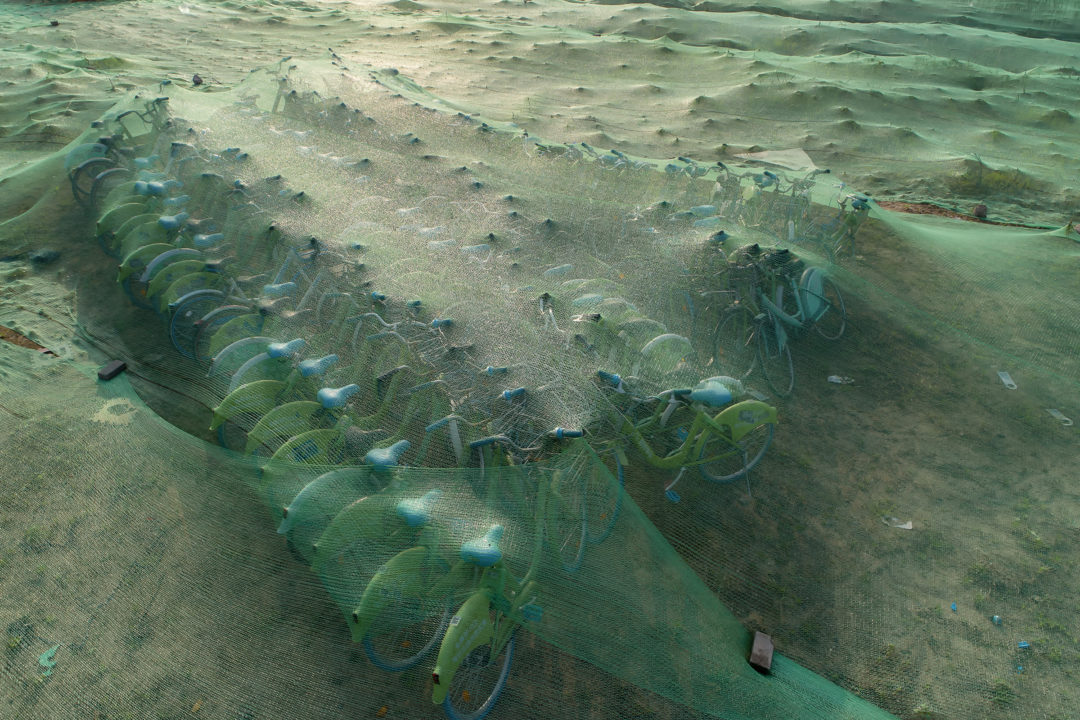

Piles of discarded Ofo bikes in Shanghai

Go to any large city in China and you’re likely to see colorful bikes strewn on every street corner. But ubiquity does not mean success in the bike sharing world, as demonstrated by the rise and fall of one of China’s bike-sharing pioneers, Ofo, this year.

Ofo, known in China as “little yellow bike”, once had a presence not just in its homeland but in countries across the globe including France and the United States, and was seen as an industry leader. Now, its CEO is on a government blacklist of debtors, media reports show queues of irate customers lining up at its Beijing office to get their money back, and the company’s entire future is in question.

Related:

Millions Queue for Refunds as Bike Sharing Pioneer Ofo Nears End of the RoadIt appears the end is nigh for one of the leaders of China’s shared bike movementArticle Dec 21, 2018

Millions Queue for Refunds as Bike Sharing Pioneer Ofo Nears End of the RoadIt appears the end is nigh for one of the leaders of China’s shared bike movementArticle Dec 21, 2018

Competition remains fierce in the bike sharing industry in China, with companies using their cash to get as many users as possible. Profit can seemingly come later. Now, however, Ofo is in a cash crunch. In November, it urged its users to transfer their deposits to a peer to peer lending company that Ofo partnered with in order to get much-needed cash, an initiative that was withdrawn after much backlash.

All of this raises a large question about the hype surrounding Chinese bike-shares and how much of it has been overinflated. In September, Bloomberg claimed that Ofo’s main rival, Mobike had just 48 million users, significantly less than the 200 million it regularly cites in press releases.

A number of new bike sharing businesses are poised to battle it out for Ofo’s market share if the yellow bike company goes under, but with the wheels seemingly coming off of the industry as a whole, it’s surely only a matter of time now until investors put the brakes on capital flows into such start-ups.

Related:

China Explained: All You Need to Know About the Bike Sharing Boom (and Bust)Article Oct 23, 2018

China Explained: All You Need to Know About the Bike Sharing Boom (and Bust)Article Oct 23, 2018

Struggling to KEEP IT “CLEAN”

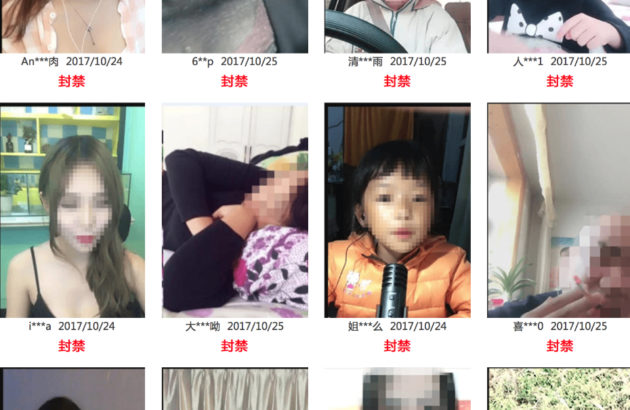

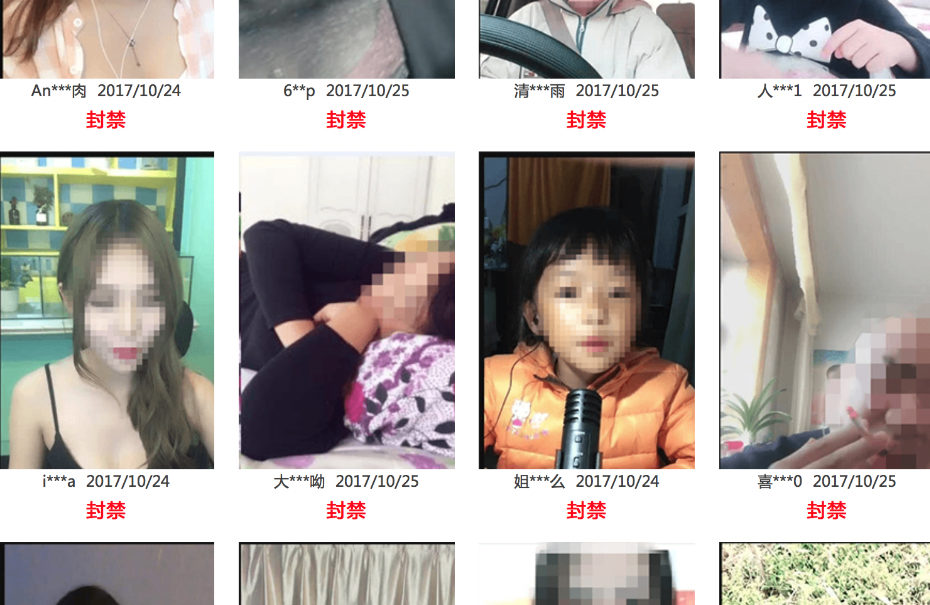

A selection of banned content on video site Hypstar earlier this year

Back in April, Chinese regulators permanently shut down a popular humor app called Neihan Duanzi thanks to its “low moral quality” and “incorrect direction.”

The move was confirmed by Jinri Toutiao, one of China’s top news aggregator apps, which also owned the humor app, according to local media reports.

The parent company — Bytedance, also the people behind wildly popular short video app TikTok (Douyin in China) — immediately vowed to re-examine its own approach and to regulate its content, an attempt to ward off further scrutiny from the authorities that would set the tone for much of 2018.

Related:

Apps Removed, Teen Livestreamers Banned in Latest Push to Filter “Vulgar” ContentArticle Apr 09, 2018

Apps Removed, Teen Livestreamers Banned in Latest Push to Filter “Vulgar” ContentArticle Apr 09, 2018

While Neihan Duanzi’s closure was perhaps the most dramatic case (with some dedicated users even briefly protesting the move in the streets), it was hardly unique. In that same week, Phoenix Television, Yahoo-like service NetEase and news platform Tiantian Kuai Bao were all ordered by the government to remove their apps from Apple’s App Store due to issues over their content. In response, Jinri Toutiao’s CEO apologized and vowed to hire 4,000 more censors to ensure that its content was wholesome.

A similar sweep for “vulgar content” also resulted in the Twitter-like Weibo platform targeting “homosexual content” earlier this year, a move that received swift condemnation and provoked a quick-fire reversal.

Online “Clean Up” Continues as Weibo Targets Homosexual Content and Grand Theft Auto [updated]Article Apr 14, 2018

Online “Clean Up” Continues as Weibo Targets Homosexual Content and Grand Theft Auto [updated]Article Apr 14, 2018

Nevertheless, tech platforms have been keen to be seen as staying on top of content censorship throughout the year, as the government continues to pay close attention to what is being posted online. In the words of a spokesperson for the Cyberspace Administration of China, “the digital space is not outside the rule of law and nobody can use the web to circulate information that violates the law.”