“Young fellow, your ophryon has darkened,” cries a mysterious old man, his eyes peering from behind tiny round sunglasses, body draped in a gown seemingly inspired by some fallen imperial dynasty. “Befell on you misfortune has!”

If you took a stroll on the streets of downtown Beijing several years ago, a warning like this would have been commonplace and come from a fortune-teller trying to pay the rent. Today, however, these urban oracles have retreated from the tourist traps and bustling thoroughfares to the city’s dusty back alleys.

Alleys like this one often host Beijing’s modern-day fortune-tellers. Image via Markus Winkler/Unsplash

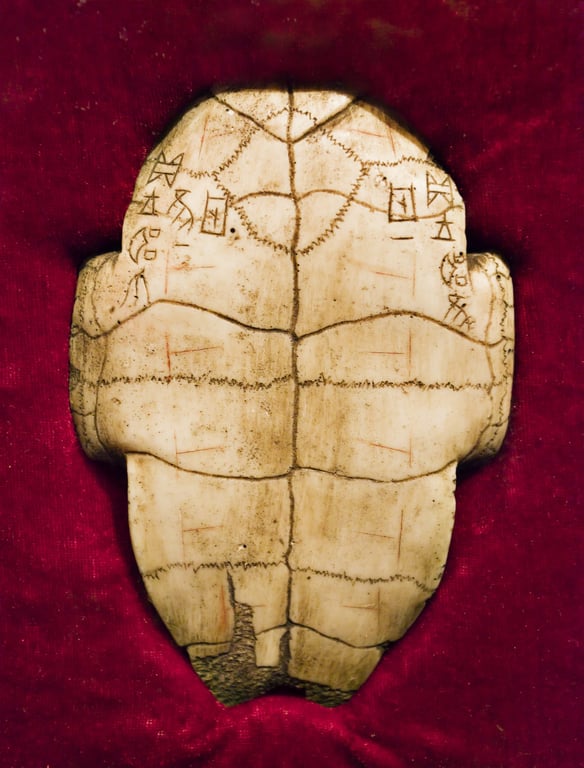

The occupation of fortune-telling can be traced back to the beginning of civilization in China. During the Shang Dynasty — the earliest governing dynasty of China established in recorded history, leaders would practice divination by interpreting the pattern of cracks on a burnt tortoise shell or the shoulder blade of an ox.

It was a period in which divination was at the forefront of decisions concerning the nation’s destiny.

The rise of the Zhou Dynasty, which immediately followed the Shang Dynasty, saw perhaps the most influential inventions in the history of Chinese fortune-telling. Among these innovations are trigrams, hexagrams, and a classic piece of literature in the field, the I Ching, which can still be found in bookstores worldwide.

Oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang Dynasty are displayed at Anyang Yin Xu Museum in Anyang city, in Central China’s Henan province. Image via Depositphotos

As the discipline developed over thousands of years, hundreds of fortune-telling schools popped up across the country, along with many individual methods.

Those who maintained the practice of I Ching instructed clients to draw from 50 yarrow stalks or three coins to determine whether good fortune or misfortune awaited them.

Others claimed a godlike understanding of every single incident that would occur in the recipient’s future, with no more information than the time and date of their birth. At the same time, they also professed they could foresee someone’s marriage and career prospects by examining their palm prints.

From Thriving to Surviving

Next to the famous Yonghe Temple (also commonly referred to as the Lama Temple) — a sacred site for tourists and Buddhists alike, on Yonghe Avenue in Beijing’s central Dongcheng district, traces of China’s once-flourishing fortune-telling tradition remain today.

Pay close attention as you pass by the avenue, where shops are mostly filled with Buddhist ritual instruments, and you may notice red or yellow cardboard signs hanging at the entrances of hutongs (small alleys surrounded by traditional courtyards, commonly found in Beijing). These hastily crafted cutouts are the unapproved signboards of remaining fortune-tellers (usually reading ‘suangua 算卦,’ ‘shengchen bazi 生辰八字,’ or ‘dashi qiming 大师起名’), and they lead to the seers’ places of business.

View of the Yonghe Temple (Lama Temple) in Beijing. Image via Depositphotos

Government officials prohibit the city’s remaining visionaries from operating street-facing shops — not even a signboard is allowed. So they stay hidden, tucked in the dark corners of Beijing’s ancient neighborhoods. Seldom will a tourist or passerby take note of, let alone follow, the humble signs.

“Not many people walk in here each day. How do I pay my bills? By doing good deeds and accumulating virtues, I guess,” says the master at Yonghe No. 151, who has spent most of his life as a fortune-teller.

But the Yonghe master might be considered one of the lucky ones. Unable to afford rent in downtown Beijing, other 21st century clairvoyants can be found sitting against a wall next to the sidewalk, equipped with nothing more than a foldable stool.

Master Mao is one of them.

“Fortune-telling here is for the poor,” he tells us. “The wealthy would rather buy costly joss sticks and ask for good fortune in that temple than pay 10 or 20 yuan [roughly 1.50-3.20 USD] to a fortune-teller.”

Moreover, those working on the street must be on constant alert for chengguan (urban managers similar to community police) who will chase them down if spotted. According to Master Mao, if captured, they will be taken into custody for anywhere from 12 to 72 hours, even after someone has provided bail.

A man working as a letter-writer and fortune-teller in Shanghai, circa 1900-1919. Image via Wikimedia

The situation is no different for people with disabilities, who often find themselves in this line of work because it has traditionally been one of the few possible sources of income.

Nowadays, a government quota requires 1.5% of job opportunities to be given to people with disabilities, but the quotas aren’t always met.

Employment for the disabled rose from below 50% in 1987 to 80% in 2007, according to data from the China Disabled Persons’ Federation. However, the national unemployment rate in 2007 was around 4-5%, so there remains a significant discrepancy.

“Massaging and fortune-telling, those are what we blind people can do for a living,” says Zhang (who only provided her surname), a blind female fortune-teller who began studying the craft with a master when she was only 16.

Running away when chengguan come for inspections, she says, is a daily ritual.

Popularity — and Rejection — Among Teens

No matter how great of deterrents legislation and policies are for the industry, there remains a demand for fortune-telling — even among Millennials and Gen Zers.

A Chinese fortune-teller in Singapore. Image via Joel Sow/Flickr

Interestingly, many teenagers in China seeking out clairvoyants today might not be aware that Chinese fortune cosmology has impacted their lives since the day they were born. In Chinese cosmology, the date and time of birth are said to influence how much each of the five fundamental elements — metal, wood, water, fire, and earth — are present in a newborn.

Misfortune, it is believed, can occur if one is deficient in a given component. In this case, a fortune-teller may recommend that parents externally supplement this element.

One common solution for these deficiencies is to give the child a name with characters that contain the missing element.

A friend of mine was “diagnosed” by a master as lacking the water element when she was born. In response, her parents decided to give her the name Hanyue (涵乐), as the character 涵 has a radical called ‘three drops of water (氵).’

In China, where it is trendy for young parents to give their children increasingly unique monikers, a name functions as both a symbol and a tool, intended to play a crucial role in forming one’s identity and individuality.

Whether this practice has any real impact on one’s fortune, we’ll let you decide. But there is no denying that the tradition has a significant impact on the lives of some Chinese citizens.

A roadside fortune-teller. Image via Lynn Lin/Flickr

Youth today who seek out details of their future will find the interpretations and explanations of fortune-telling masters to be vague. This vagueness is certainly intentional, because whatever an individual’s personal situation, they are perhaps more likely to perceive the predictions bestowed upon them as accurate.

Teenagers are recurring clients of Master Mao. Faced with intense pressure from the Gaokao (China’s college entrance examination) and societal pressure after graduation, young people go to modern-day soothsayers to find answers, or at least some form of external relief for their stress.

Zhao Jiaqi, a 17-year-old high school student who was looking for “certainties in the future,” dove into the I Ching, hexagrams, and the nature of balance, as described by Yin and Yang.

He read the I Ching and its interpretations, along with popular methodologies developed by others based on the book’s content. But rather than certainty, he found only “chaos.”

“The fortune-telling system is built not upon truth, not even a theory, but bunches of opinions,” says Zhao. “People would, for example, take an interpretation, which is an opinion, of I Ching, as a foundation of their methodology.”

A fortune-teller in Southwest China’s Yunnan province in 2005. Image via J/Flickr

Leaning into his skepticism, he attempted to translate a famous fortune-telling method — na jia (纳甲) — into an algorithm that would tell one’s fortune after inputting information like a birthdate and the results of a coin flip.

Unsurprisingly, he hit a roadblock: The book’s logic was inconsistent and contained far-fetched exceptions indicating that the author was trying to settle logical errors.

So Zhao decided to conduct a personal experiment. Several days later, he found a master and received a reading. The results indicated misfortune.

But unlike most fortune seekers, who often find their fortunes to be accurate by way of confirmation bias, he chose to believe the opposite. In the following days, everything seemed to go smoothly — he even had a profound and fruitful conversation with his girlfriend that, according to the hexagram, was not supposed to yield a desirable outcome.

“It only makes me feel powerless,” says Zhao, smacked with a reality that contradicts any notion of mystic order he was once open to believing.

Following this realization, Zhao came to the arguably logical decision to abandon fortune-telling and his attempts to predict the future.

Invasion of Western Astrology

As the Chinese fortune-telling industry struggles to survive, Western fortune-telling methods, like astrology and tarot cards, have found acceptance and genuine interest from some groups in China.

Nowadays, as most young people in China can probably agree, zodiac signs have become a crucial piece of information in many social situations.

On Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, a person’s zodiac sign is listed along with a user’s name, gender, and age on their profile page. And in social settings, it is far more common to hear people discussing their Western astrology signs and related traits than comparing Chinese astrological signs.

A fortune-teller using tarot cards. Image via Depositphotos

“The theories of Western and Chinese fortune telling overlap. They both explore how, at a specific moment, the momentum and energy of celestial bodies shape an individual,” says Susu, a ‘mental masseur’ who studies and practices Western astrology.

She has also gone through some of the Chinese fortune-telling classics. Whether the two perfectly resemble each other requires further investigation, says Susu, but she asserts that the theories do share some similarities, such as agreeing on the importance of birth dates and constellations.

So what distinguishes Western and Chinese fortune-telling? And how has Western cosmology so successfully infringed on the territory of its native counterpart?

Related:

Chinese and Western Zodiacs Are Similar, but Also Strikingly DifferentWhile not a scientifically rooted discipline, astrology is a ubiquitous cultural phenomenon in both East and WestArticle Feb 01, 2022

Chinese and Western Zodiacs Are Similar, but Also Strikingly DifferentWhile not a scientifically rooted discipline, astrology is a ubiquitous cultural phenomenon in both East and WestArticle Feb 01, 2022

While China’s youth may gravitate to the far reaches of neighborhood hutongs in search of answers to life’s existential questions, to some young people, Western astrology offers something lighter — providing fodder for gossip and friendly conversation.

Additionally, whereas content relating to star signs is readily available on social media and astrology-specific apps, Chinese fortune-telling requires the physical presence of a master, making the reach of homegrown practices far smaller.

The flipside of this tradeoff is that Chinese fortune-telling contains an element of mystery, since only the practitioners of these methodologies have access to the ‘knowledge.’

But mystique is a double-edged sword. While it adds an element of seriousness, the number of consumers a master can reach is limited. There are simply not enough people like Zhao Jiaqi in the younger generation to keep the industry alive.

The Unpredictable Fortune of China’s Seers

Modern technology offers Chinese clairvoyants both the promise of reaching a larger audience and the risk of fading further into obscurity.

Nowadays, as teens are inundated with apps competing to extract their attention and energy, following trends in mass media is arguably the most practical path for the fortune-telling industry to find relevance in an ever-changing society.

Embracing new tech is not a novel approach. When the internet era began decades ago, many fortune-tellers established web pages. When the age of artificial intelligence dawned a few years ago, AI fortune-telling emerged.

When smartphone applications became the trend, fortune-telling apps went online. Now, fortune-tellers in China also offer readings via WeChat or other social media platforms.

Back in 2019, South China Morning Post’s tech publication Abacus reported that Chinese media outlets had taken notice of AI-based face and palm readings being offered on WeChat. State-backed publication Xinhua wrote at the time that the fortune-telling services pose a risk to citizens’ biometric data and are gimmicky and unscientific.

A fortune-teller is plying his trade in Hong Kong. Image via Scott Edmunds/Flickr

As short video platforms like TikTok and its Chinese sister app Douyin become the center of youth social media traffic, it might seem logical to assume that the industry will, once again, evolve accordingly.

However, the general consensus in China’s mainstream media, which represents the government’s stance (in most cases), remains that online fortune-telling is nothing short of a scam. As recently as January of this year, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) launched a crackdown on superstitious beliefs online — including fortune-telling and online divination.

Considering the state’s rigorous monitoring and censoring of video content on short video platforms in China, the likelihood of a modern-day audiovisual renaissance for the industry is not promising.

At this point, whether or not fortune-telling is authentic doesn’t matter. The once-glorious occupation faces a murky, difficult-to-predict future, which is somewhat ironic — if you ask me.

Cover image via Wikimedia