It’s one of the most famous images in American history. One hundred fifty years ago this month, dozens of men, a few holding celebratory bottles of liquor, from the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads were photographed in honor of the completion of the First Transcontinental Railway.

There are workers and bosses. Politicians and businessmen. But one group is conspicuously absent.

There are no Chinese faces among the men celebrating the incredible feat of engineering that linked a nation together and marked the beginning of the United States’ rise as a continental empire and a global power.

The Erasure of Asians from American History

As historian Gordon H. Chang writes in his new book, Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad:

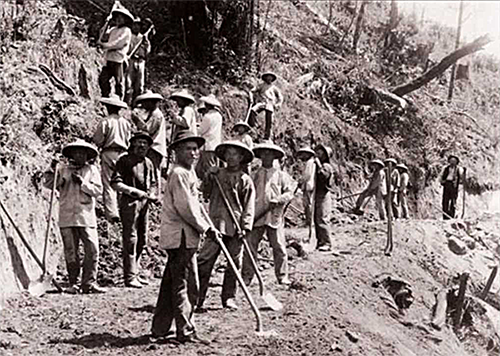

“For five years, from 1864 to 1869, Chinese constituted by far the largest single workforce in American industry to that date, not surpassed in numbers until the Industrial Revolution in the late nineteenth century. Their massed presence along the construction route astonished journalists and travelers who witnessed them living and toiling under the most difficult of conditions.”

The absence of Chinese in this famous photo would come to symbolize the exclusion and erasure of Asians from American history. As many as 20,000 Chinese laborers worked to build the transcontinental railway. They laid miles of tracks through the tall and tough granite of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, working in narrow tunnels with explosives, engineering bridges across high chasms and often doing the work white laborers deemed too dirty, degrading, or dangerous.

Much of the work was done by hand, using shovels and axes, carts and horses. It was backbreaking labor for which the Chinese working for the Continental Pacific Railway were paid only 1/3 what their Irish immigrant counterparts were earning laying track through the prairies of Nebraska and Wyoming for the rival Union Pacific.

California politicians initially rejected the idea of using Chinese workers. Leland Stanford, the notoriously racist governor of California and the founder of a certain prestigious university, was among those who questioned whether Chinese would have the ability or temperament for the hard work of building the railroad. It was railway executive Charles Crocker who gets the credit for deciding to use Chinese laborers.

Related:

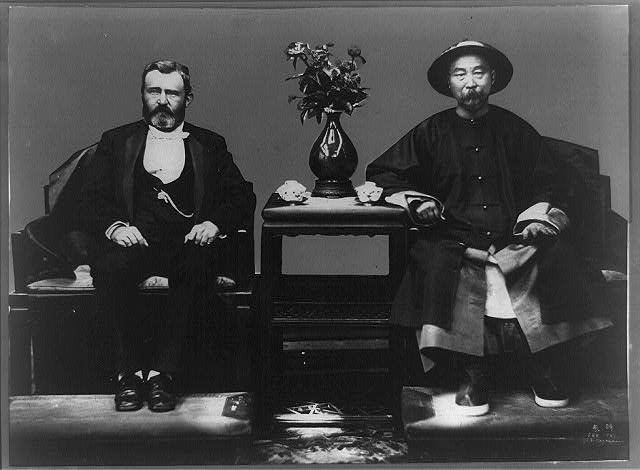

When Ulysses S. Grant Met General Li (Part 1)Article Jan 21, 2018

When Ulysses S. Grant Met General Li (Part 1)Article Jan 21, 2018

When asked if the Chinese had the fortitude to tackle the formidable stone of the Sierra Nevadas, Crocker reportedly said, “Did they not build the Chinese wall, the biggest piece of masonry in the world?”

(Crocker’s support for Chinese workers had limits. He infamously broke a strike by Chinese laborers working in snowbound Donner Pass by withholding shipments of food and supplies — because that’s always worked out well for folks trapped in that particular nook of the Sierra Nevadas.)

How Did the Chinese Laborers Come to be There?

Chinese immigrants had been coming to California before there was a railroad to be built. Many Chinese undertook the long, perilous journey across the world to find their fortunes in the California gold rush. They landed at San Francisco, “The Old Gold Mountain,” and found their way into mining camps and settlements.

A mural by Francisco Aquino in San Francisco’s Chinatown area (photo: MK Feeney)

The pull of riches was strong, especially for people from coastal provinces like Guangdong and Fujian who long had a culture of sojourners traveling long distances looking for new opportunities to make life better for families back home. At the same time, life in southern China was especially difficult in the middle of the 19th century. The Taiping War was raging, a conflict that some historians estimate accounted for between 20 and 30 million casualties and which devastated the economy of entire regions. It would be years before survivors of this war would be able to put their lives back together.

Chinese immigrants escaped war and poverty looking for work and wealth. Mostly they found racism and hostility. As early as 1850, Californian politicians and their white supporters sought ways to undermine the legal status of Chinese and other Asian immigrants. Political speeches, newspaper articles, and editorial cartoons depicted the Chinese as unassimilable, unwilling to learn English, prone to crime and degrading behavior, and a sexual threat to white women. Ultimately, the Chinese would become the first group specifically targeted for exclusion under the law with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.

Isn’t it nice how we’ve progressed as a country? Moving on…

Related:

American Business and Chinese Nationalism: Lessons from 1905Article Apr 16, 2018

American Business and Chinese Nationalism: Lessons from 1905Article Apr 16, 2018

Beyond the Transcontinental Railway: Laying the Foundations for Modern America

Ironically, the precarious legal status of many Chinese workers is what made them so attractive to employers and vilified by their white counterparts. Whites mistook a lack of legal rights for Chinese “docility” and mistook unfair labor contracts signed through middlemen with a willingness to work for low wages.

When the work was finished, many of these now highly skilled laborers dispersed across the United States. They helped build the infrastructure which dramatically transformed the economics and ecology of western North America. They also continued to be the victims of racism, and an all-too-convenient target for politicians playing to the insecure xenophobia of their constituents.

As Chang argues, the Chinese worker built the railway which made it possible for large numbers of white workers to travel easily into the west. Once there, the newcomers demanded jobs and saw the Chinese as a threat. The result was violence. Rioters killed 18 Chinese people in Los Angeles in 1871. 23 Chinese were lynched at Rock Springs, Wyoming in 1885. In both cases, no one was punished for taking part in the killings.

The building of the Transcontinental Railway was an incredible achievement. It was a turning point in American history. It connected a nation torn apart by its brutal civil war. It was the beginning of the American empire — Manifest Destiny realized in iron and blood. The ambitions of the men who dreamed of a railway across the United States did not end at the western edge of the Pacific. Trade with China and India had been part of the American Dream for as long as the United States had existed.

And it was Chinese immigrants, among others and often much more than others, who made that possible one hundred fifty years ago. Their sacrifice and toil deserves our memory and recognition.