On weekends, Shanghai’s People’s Park becomes the temporary home to rows upon rows of opened umbrellas. Tacked onto each umbrella is a resume of sorts, advertising the details a young, unmarried person in hopes that a match can be made with others in the park.

28-year-old Yangyang Guo admits that she’s walked through this park before, examining the rows of umbrellas. Like many women her age, marriage was always important to her, its importance reflected back at her by her friends and family. And like still more her age, her idea of marriage was largely shaped by the model her parents provided for her.

Related:

Film of Shanghai Marriage Market by “Leftover Woman” Goes ViralArticle Mar 19, 2018

Film of Shanghai Marriage Market by “Leftover Woman” Goes ViralArticle Mar 19, 2018

Finding they had this much in common, Guo and three other theater-makers — two from China, one Egyptian-American — set out to explore where their experiences with marriage, relationships, family, and divorce converged and diverged, using Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House as a jumping off point.

Doll’s House — a seminal play in the early Western feminist movement — had a significant impact in China as well as in Europe. The text fell into the hands of writer Lu Xun, a key idealist behind the May Fourth movement, who translated the text for a wider audience. Playwright Hu Shi later took the story and penned The Greatest Event in Life in 1919, which saw protagonist Tian Yamei leaving her family’s house at the end of the play, rather than her husband, and choosing to pursue the love of her own choice.

Inspired by both stories, Guo and fellow practitioners Selena Lu, Lin Cuixi, and Lelia TahaBurt chose to set their play in today’s Shanghai — a metropolis that’s historically been at the intersection for cross-cultural conversation, but still facing many of the same gender inequity issues riddled throughout capitalist societies.

Despite growing up near Shanghai with parents “on the more liberal side,” Lin still wasn’t exempt from any of the pressure to get married. She recalls:

“My mom was very anxious about me not getting married or getting a boyfriend. For a while she was breaking down in front of me [almost] every week because of this. It was intense.”

One of five worldwide to win an Ibsen Award in 2019, their performance is less of a straightforward play than a series of loosely strung-together vignettes. At the performance’s Shanghai debut produced by China-based organization Ibsen International, the four actresses belted a song about feminism in English over rock guitar. Soon after, Guo was the contestant in a dating game show, evaluating men in Chinese from the audience. Over an hour, the women sing, dance, chant, convulse, and share their stories with the audience, all while climbing up, down and through the set’s lone centerpiece — a giant, inflatable structure made of the Chinese characters for “woman” (nv 女) and “home” (jia 家).

Having had varying lengths of time abroad and proximity to Chinese culture, the stories these four share are naturally very different. It becomes clear that even among the three Chinese women, their families could not be more dissimilar. Also born near Shanghai, Lu says that she grew up in a giant, affectionate 10-person unit of close and extended family members. In a monologue, she says that having grown up in such a loving environment, she had a lot of faith in marriage and wants to have a large family herself.

Her biggest difficulty, however, was realizing later on that she had never once in her life been alone. “I started to question why my existence has to be relational,” she says. “Why is being single not an equally legitimate way of living? So I promised myself that I would stay single for at least three years […] to understand what it means to be alone in this world.”

Guo, who was born in Beijing and raised in the US, grew up seeing what she thought was a happy marriage. But not until her mother got sick — and eventually passed away from cancer — did she realize the inequities within her parent’s relationship. She says:

“Even though both my parents worked, it always fell on my mom to pick me and my sister up from school, clean the house, cook… My dad wouldn’t even bother to refill his own rice bowl. Especially after my mom got sick, it made me question this ‘ideal’ marriage. Was this fair to my mom — or to either of my parents?”

Yet when it comes to their views, the four have a lot more common ground. For instance, though they mockingly refer to themselves as “leftover women” — a term in China used for unmarried women over 25 — none of them genuinely subscribe to the label. “To me, it’s a sexist label created by people who define women by their marital status,” says Guo. “I think I’ve become a better person as I’ve aged.”

TahaBurt agrees, adding that whether or not one grew up in China, the label is hard to get out from under. “Any time I feel an actual emotional impact from the ‘leftover’ label, I know I have to do some thinking.”

Most of the women also feel that in the years since China’s opening up in 1978, the country has both gotten better and worse in terms of feminist issues. “In some ways, back in the [Maoist] era, women had more status than they do now,” says Lin.

“From one perspective, the propaganda diminished femininity in women’s outer appearance, and for a time, that made people believe that women were just as strong as men. Which has its downsides — my grandma only had 38 days of maternity leave because of this ideology.”

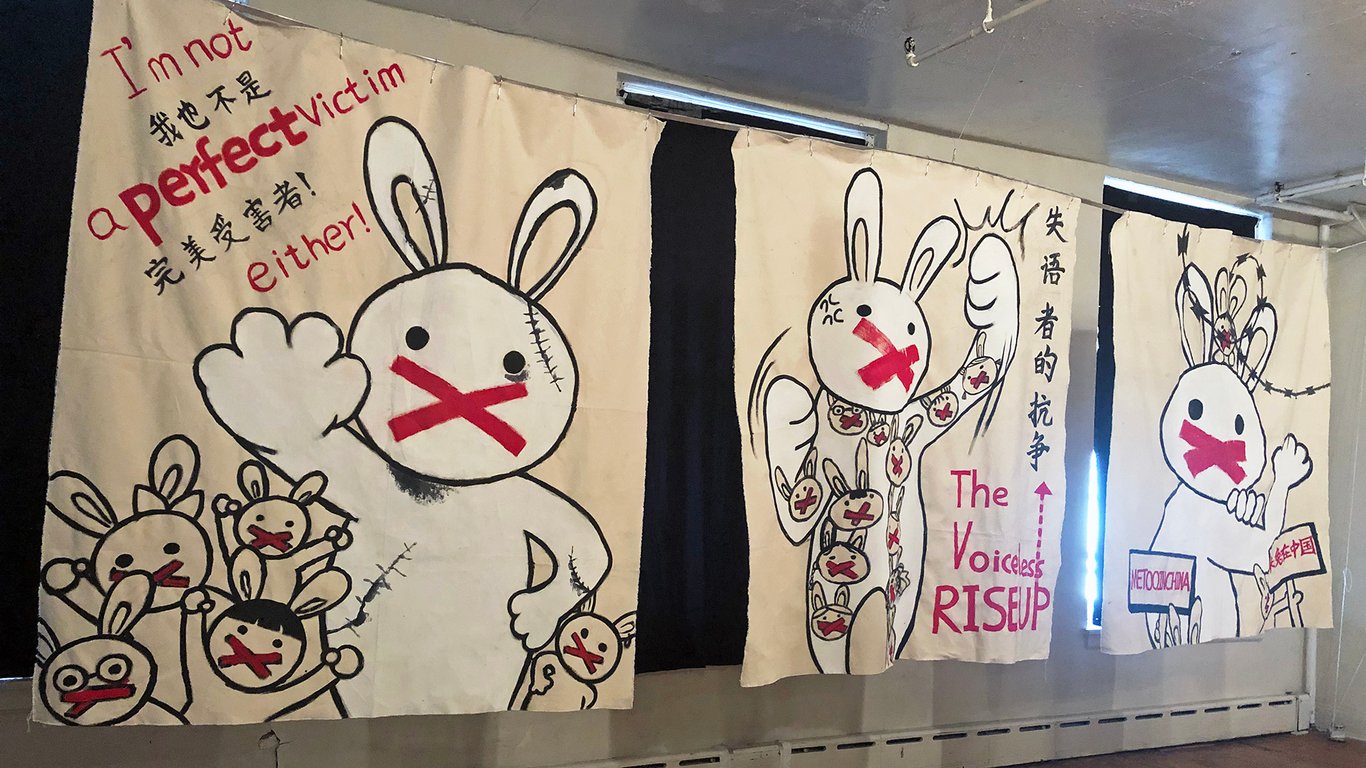

As China has increasingly embraced capitalism over the past 30 years, International Women’s Day on March 8 is repeatedly marketed as a “shopping day” for women. And when the #MeToo movement reached China, online discussion of, as well as public events associated with, the movement were swiftly censored or shut down.

Related:

With New York #MeToo Exhibition, Chinese Feminism Finds a Home AbroadAfter being shut down in two Chinese cities, this “very DIY” exhibition – and the feminist movement it stems from – aims to spark discussion abroadArticle Oct 23, 2019

With New York #MeToo Exhibition, Chinese Feminism Finds a Home AbroadAfter being shut down in two Chinese cities, this “very DIY” exhibition – and the feminist movement it stems from – aims to spark discussion abroadArticle Oct 23, 2019

The word “feminism” also has a complicated legacy in China, as it does elsewhere. While China has certainly seen progress in discussing feminist issues, the term is just as often seen as a dirty word that women don’t want to associate themselves with. “People’s definitions of feminism are so different and so subjective,” says Lin.

“What feminism is is very clearly defined, but everyone has their own definition of what they should do as a feminist.

“There’s very jingzhi — very classy — feminists, where you’re only powerful if you take care of yourself. Some people think that’s a valuable tool, and other some people don’t buy into that shit. There’s a lot of ambiguity around the word.”

But there are upsides as well, such as a perceivable increase in awareness — and talk — around feminist issues. Guo points out that prior to this year, International Women’s Day on March 8 was almost always called “Goddess Day” (Nvshenjie 女神节), but some netizens accused the name of being sexist, for implying beauty is women’s only power. Over the last two years, younger women especially have banded together online to criticize marriage, restrictive beauty standards, the media coverage of female nurses during the Covid-19 outbreak, and even virtual idols.

Related:

Why China’s Millennials Are at War with Marriage and Having BabiesPost-‘90s millennials online are saying, “death to the next generation”Article Sep 11, 2019

Why China’s Millennials Are at War with Marriage and Having BabiesPost-‘90s millennials online are saying, “death to the next generation”Article Sep 11, 2019

Guo continues, “That said, China is huge, and I think we only speak for [first- and second-tier] cities, because economics have a lot to do with it. There are many people who are not doing well economically, and are [therefore] looking for someone who has a stable job, someone who has a house, a car. Their priority is to find stability outside themselves.”

The quartet plan to tinker with some parts of the play, and once the Covid-19 pandemic subsides, eventually take it on tour to a wider variety of audiences.

“People are living in their own echo chambers. It’s easier for them just hearing what they want to hear,” says Lin. “That’s why we have to talk to the other side.”

All photos: courtesy Ibsen International