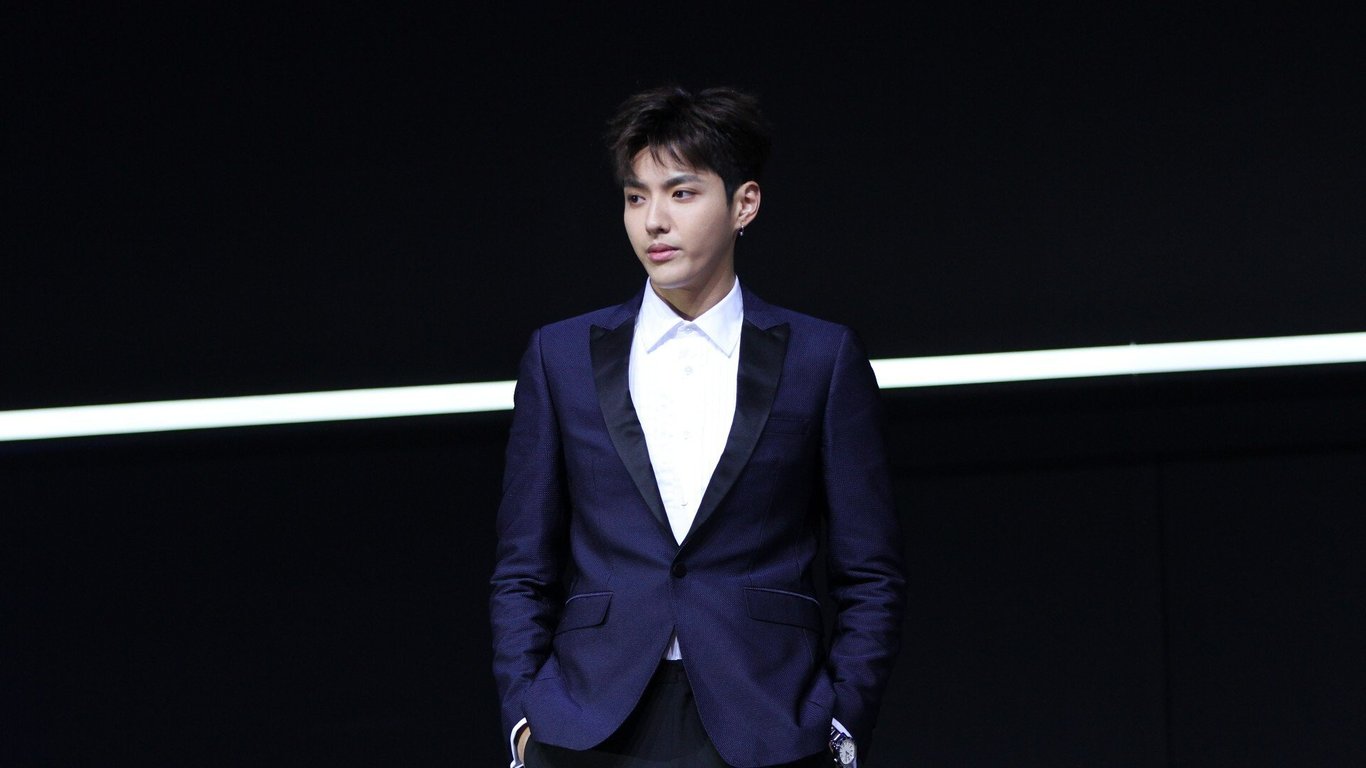

The increasing popularity of androgynous Chinese male celebrities over the last decade may at first seem like a South Korean import. The term “little fresh meat,” or xiaoxianrou (小鲜肉), has gained popularity as a descriptor for Chinese pop stars and actors such as Kris Wu and Luhan, and these young celebrities have tended to straddle the musical worlds within both countries.

However, this beautiful, more petite male ideal actually has its roots in traditional Chinese fiction and performing arts. The idea of wen (文) and wu (武) types of male performers denote opposite ends of an entertainment masculinity spectrum that has been in use since the days of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), with wen used to describe more effeminate characters, similar in ways to “little fresh meat,” while wu types tend to be more martial and gruff.

Related:

Hit Web Series “The Longest Day in Chang’an” is Winning the Chinese Internet (and is Now Streaming on Amazon)Amid a film industry crackdown, the historically detailed Tang Dynasty epic is this summer’s breakout titleArticle Jul 22, 2019

Hit Web Series “The Longest Day in Chang’an” is Winning the Chinese Internet (and is Now Streaming on Amazon)Amid a film industry crackdown, the historically detailed Tang Dynasty epic is this summer’s breakout titleArticle Jul 22, 2019

A fantastic example of these two male types in action can be seen in The Longest Day in Chang’an, one of the most popular Chinese TV shows of 2019. The series is an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Ma Boyong, set during the Tang Dynasty, and features two male leads: a former death row prisoner and a young government official.

The prisoner Zhang Xiaojing, played by Lei Jiayin, is a former soldier released from jail to help solve a crime. Meanwhile Li Bi is a young but powerful official, played by Jackson Yee of TFBoys fame, who orders Zhang’s release and is responsible for the Tang capital’s security. The duo team up to try to prevent a group of terrorists from assassinating the emperor on the night of the Lantern Festival.

The pairing of these two characters highlights some interesting aspects of Chinese masculinity, but this odd couple are not necessarily the only archetypes. As scholar Kam Louie points out in his book Theorizing Chinese Masculinity, the opposite of Chinese masculinity is not femininity — in fact it may be easier to imagine Chinese masculinity as a spectrum. Perusing literary classics from the Tang and Qing Dynasties help us to understand the legacy of these ideas of masculinity in Chinese entertainment.

Wu Masculinity

On one end of this spectrum is “wu,” or the martial form of masculinity, with figures that are generally physically strong and are associated with the military or are knowledgeable in martial arts or weaponry.

An early literary example of a wu masculine figure is Curly Beard from Tang romance The Curly Bearded Hero (虯髯客傳), by Du Guangting. Surnamed Zhang and the third child of his family, the reader only knows of him by his nickname, Curly Beard. He enters the story riding on a lame donkey and enjoying a cannibalistic meal of human head, heart, and liver.

A later, but also notable, work with many wu masculine figures is The Water Margin (水浒传) by Shi Nai’an from the Ming Dynasty, with one hundred and eight “good fellows” who engage in a variety of rebellious behaviors against the government.

One interesting aspect of traditional portrayals of wu male characters is that they have for the most part limited their relationships to other men, and they never partake in romantic relationships or display an interest in the opposite sex.

Wen Masculinity

On the other end of the spectrum is the “wen” form of masculinity, which is traditionally portrayed as being entangled in romantic relationships with one or more women. The archetype of the wen masculine figure was also established in Tang romances, with prominent figures such as the male protagonists from Bai Xingjian’s Tang Dynasty novella, The Tale of Li Wa (李娃传) and Yuan Zhen’s romance Story of Yingying (莺莺传).

Later, wen characters were typically embodied in the genre of scholar-beauty fiction, which were very similar in content and form, but still enjoyed huge popularity among Chinese readers. As Cuncun Wu points out in her 2003 essay “Beautiful Boys Made Up as Beautiful Girls,” the feminine wen masculinity was actually the ideal type of masculinity during the late imperial era.

At that point in history, a muscular, rough and tough image of men had been closely associated with that which is non-Chinese. The unending military and cultural interactions with non-Chinese northern neighbors from the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) well into the Qing (1644-1912 CE) had significantly altered what was considered desirable in a Chinese man over the centuries.

Related:

The Year In “Little Fresh Meat”: Young Chinese Male Stars Who Killed It In 2019Whether they’re part of a CIA plot or simply the sexy stars Chinese fans want, it’s been a big year for these male celebsArticle Nov 26, 2019

The Year In “Little Fresh Meat”: Young Chinese Male Stars Who Killed It In 2019Whether they’re part of a CIA plot or simply the sexy stars Chinese fans want, it’s been a big year for these male celebsArticle Nov 26, 2019

The Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦), by Cao Xueqin from the Qing Dynasty, is one telling example of masculine ideals at the time. Cuncun Wu notes that Cao’s work dismantles numerous literary clichés, but still portrays a male protagonist that conforms with the male qualities in vogue at the time. The main character Jia Baoyu is physically attractive in a traditionally feminine way; he is also young, sensitive and emotional.

Like other young scholar protagonists from fiction and theater produced during that time, Jia’s youthfulness and beauty are essential characteristics in helping readers and audiences quickly identify who the main character is. The more physically attractive the young man is, the more intelligent and virtuous.

It’s important to remember as well that all of these works of fiction and theater were written by men over the centuries, targeting both male and female audiences. There was absolutely no female input in these literary trends, hence the femininity and masculinity displayed in these works were purely male inventions. Ideal masculinity being more feminine than women was the scholarly class’ self-image. As such, this active emasculation of sorts was not due to any outside forces.

Masculinity in Modern Times

Though we can still see the legacy of these literary trends in the contemporary entertainment industry, male celebrities these days are generally situated more towards the center of the spectrum. They are no longer too frail to support their own clothing, but rather are expected to display their youthful energy through singing and dancing.

Even male protagonists in more martial or military contexts are shown with romantic interests and families. Take, for example, Wu Jing’s character in the Wolf Warrior franchise, who is depicted as a caring friend as well as boyfriend. This stands in stark contrast to the Asian masculinities more familiar to US or European audiences, such as those portrayed by Bruce Lee, whose characters are rarely — if ever — involved in romantic relationships. In China, there are rarely flagrant display of muscles or sexual promiscuity from such heroes.

Related:

Toying with Taboo: Daoist Magic, Homosexuality and the Story Behind “The Untamed”The popular TV show is suddenly at the heart of a major controversy, but censorship of its central themes is nothing newArticle Mar 10, 2020

Toying with Taboo: Daoist Magic, Homosexuality and the Story Behind “The Untamed”The popular TV show is suddenly at the heart of a major controversy, but censorship of its central themes is nothing newArticle Mar 10, 2020

Folding these ideas of wen masculinity into contemporary entertainment is not difficult. Just consider Jackson Yee’s character in The Longest Day in Chang’an. Yee was only 17 years old when the series was in production, and was still studying for the gaokao exams during his breaks between shoots. Yee, as well as the duo from The Untamed — Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo — exemplify the connection between the contemporary “little fresh meat” characteristics and the older wen character traits, while showing off the long legacy of these more gentle and distinctly attractive characters in Chinese entertainment.

All illustrations: Helen Haoyi Yu