Elaborate period drama The Untamed was one of the most popular web series in China last summer.

Produced by Tencent (and currently streaming on Netflix), The Untamed is a live-action web series adaptation of the “boys’ love” (BL) online novel, Modao Zushi by Moxiangtongxiu. The novel has also been adapted into an audio drama, animation, and series of comic books within a very short period of time — but the Tencent version is what has made it a mainstream cultural phenomenon.

Now, it’s at the centre of an online storm after fanfiction site AO3 was banned in China following a targeted campaign by fans of idol Xiao Zhan, who plays one of the lead characters in the show, and he himself became the target of an organized online revenge movement. Yet interestingly, the themes of censorship and controversy are nothing new when it comes to Moxiangtongxiu’s tale.

A Kind of Magic

There is no official translated title of the original novel, but English fan communities refer to it as either Founder of Diabolism or Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation. (Here we’ll refer to the novel in its transliteration, Modao Zushi.) The original novel features a homosexual relationship between two central characters, Wei Ying and Lan Zhan, and the story is set in a pre-modern fantasy realm. The main characters all practice Daoist magic through their use of weapons and musical instruments, and are able to cast spells and curses.

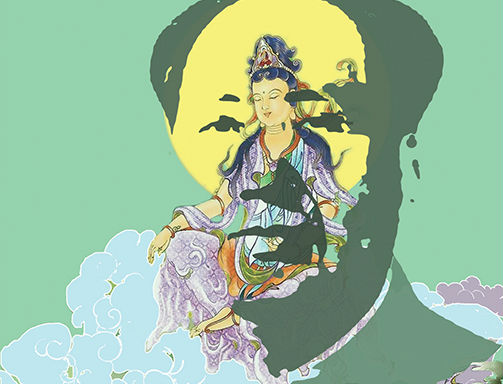

While the depiction of the homosexual relationship central to the novel has proven a problem in visual adaptation, given China’s overall conservative attitude towards LGBTQ+ issues, the element of Daoist magic key to Modao Zushi‘s narrative also represents a cultural trope that was once considered taboo in modern China.

Stories about Daoist magic were actually banned in the early 1900s, even though it had been part of the Chinese imagination for hundreds of years

Related:

Stories about Daoist magic were actually banned in the early 1900s, even though they had been part of the Chinese imagination for hundreds of years. A few Tang dynasty romances feature female assassins trained in Daoist magic, such as Nie Yinniang and Hongxian(from their eponymous stories), who possess supernatural speed and precision in their movements. The New Culture and May Fourth Movements in the 1900s cast many traditional literary genres in a negative light, including the so-called “Mandarin Ducks and Butterflies” romances, martial arts epics, and tales about Daoist magic. These genres were considered dangerous for youths, or extremely backwards, because they did not address “progressive” issues such as science, democracy, or overriding national concerns.

Tales featuring Daoist tropes of of reclusive immortals or martial artists in the mountains were regarded as especially dangerous. As John Christopher Hamm notes in his book Paper Swordsman: Jin Yong and the Modern Chinese Martial Arts Novel, the concern at the time was that such stories may lure the young and gullible into the mountains for good. It was also around this time that many of the modern literary giants, such as Lu Xun and Yu Dafi, came to fame. The ban on previously popular genres continued from the Republican era (1912-1949) into Communist China, in which only socialism and realism were allowed for several decades.

You might also like:

Author Xueting Christine Ni Explains the Culture Behind China’s Crowded PantheonArticle May 30, 2018

Author Xueting Christine Ni Explains the Culture Behind China’s Crowded PantheonArticle May 30, 2018

The exiled genres of martial arts and magic were replanted in Sinophone centers outside of mainland China. This process was most effective in Hong Kong, where the British colonial government was loose in governing Chinese materials.

New School Martial Arts

Thus a “New School Martial Arts” (Xinpai Wuxia) was able to flourish in the British colony, with notable authors like Jin Yong and Liang Yusheng paving the way in the 1950s. New School Martial Arts authors mostly followed a realistic portrayal of martial arts and combat, differentiating their content from the Dao-seeking flying swordsmen of earlier 20th century writers like Huanzhulouzhu.

Daoist magic reached its peak in popular culture and Hong Kong media between in the 1980s and ’90s, particularly in the form of films and TV series featuring monsters culled from Daoist lore, like the Mr. Vampire film franchise and the successful television show My Date with a Vampire.

Related:

The later revival of Daoist magic in mainland Chinese media worked differently, favoring love stories mixing traditional and Western fantasy elements. Modao Zushi is perhaps the most popular and illustrative example of the revival of Daoist elements in contemporary Chinese media.

Untamed Zombies

In every version of the Modao Zushi, the story begins in the middle of the plot. Wei Ying awakens in a new body, having returned from death through a forceful sacrificial rite. Wei Ying’s soul is injected into the body of Mo Xuanyu, who willingly gives it up. In return, he asks Wei Ying to kill his enemies for him. In Mo’s body, Wei Ying re-encounters all of the most important people from his previous life. His comeback is part of a larger scheme, but at the same time, Wei Ying discovers the truth to his own downfall more than a decade ago, as well as his unrequited love, Lan Zhan.

Wei Ying’s return to the living realm is a good metaphor for the return of Daoist magic in contemporary Chinese media — even though Wei Ying died for thirteen years, and Daoist magic disappeared from mainland media for almost a century.

Straying from standard practice of the Dao through sword techniques, Wei Ying breaks ground in the magical Daoist world through inventing new tools, as well as reviving the consciousness of “fierce cadavers,” or xiongshi. Xiongshi is a neologism in the world of Modao Zushi, a cross between the traditional “catatonic cadaver” (jiangshi) and the Western zombie (sangshi), physically mobile but unconscious.

One important character in Modao Zushi and The Untamed is the Ghost General Wen Ning, who was turned into a “fierce cadaver” through spells, but then regained his consciousness after coming under the care of Wei Ying. (Wei Ying’s ability to control the undead applies to both “fierce cadavers” and ghosts.)

Jiangshi, or “hopping zombies,” were a popular feature in ’80s and ’90s Hong Kong cinema

Unlike the bloodsucking vampires of European myth that sleep in coffins and transform into bats, the undead of the Daoist canon are closer to the Western zombie. In many older Hong Kong films, these undead are dressed in Qing dynasty official robes, with yellow paper talismans stuck on their foreheads, and jump in a single-file line with their arms raised up in front. A Daoist priest has raised the bodies to herd them in the dead of night, delivering each one back to their ancestral homes to be buried. The “fierce cadavers” under Wei Ying’s control in Modao Zushi, by contrast, are more like an army that can no longer feel fear or pain in combat.

From Marginalized to the Mainstream

Online novels like Modao Zushi are typically written by amateurs. Online publishing platforms Jinjiang and Qidian have risen in recent years, driven in large part by click-generating “boys’ love” novels. Authors who reach a certain number of views will be signed on as a contract author, receiving monetary support from the platform.

Online publishing platforms Jinjiang and Qidian have risen in recent years, driven in large part by click-generating “boys’ love” novels

Although these online authors are often able to skirt the government censorship that traditional publications are subject to, Jinjiang and Qidian both have internal censors that sweep the posts for overly pornographic or violent content before anything can go public. Authors also appear to self-censor quite often, avoiding phrases or numbers such as “1989” that might automatically trigger online censorship.

Related:

Here’s What Chinese Netizens Were Streaming This SummerIn a land without Netflix, these are the shows and video platforms that put up the numbers over the summer monthsArticle Sep 11, 2019

Here’s What Chinese Netizens Were Streaming This SummerIn a land without Netflix, these are the shows and video platforms that put up the numbers over the summer monthsArticle Sep 11, 2019

Though originally working in marginalized spaces of fandom, the runaway success of online novels has folded this genre of fiction into the mainstream, completely revolutionizing the Chinese mediascape. There are dozens of recently produced or in-productions films and TV series based on online novels, where traditional elements like immortality and flying swordsmen are now infused with contemporary trends from other parts of the world.

The rise in popularity of zombies in Western cinema and television, for example, has had a huge impact on East Asian productions. The fierce cadavers in Modao Zushi have either risen from the dead, or been engineered to pose as an indestructible army. It is especially interesting that different versions of Modao Zushi have different names for these cadavers. While the original novel and subsequent audio drama use the neologism xiongshi, these same entities are called “running cadavers” (zoushi) in the animated version, and “puppets” (kuilei) in the live-action series. When referred to as puppets, not only do the nefarious intentions of the master become minimized — the murderous nature of the army is also played down. Most importantly, there is no verbal association between puppets and magic.

Related:

Chinese Comic “Zombie Brother” is Getting a Hollywood AdaptationThe popular Chinese comic, about a city where the water supply has been contaminated by an ancient coffin, is getting a live-action version set in NYCArticle Sep 17, 2019

Chinese Comic “Zombie Brother” is Getting a Hollywood AdaptationThe popular Chinese comic, about a city where the water supply has been contaminated by an ancient coffin, is getting a live-action version set in NYCArticle Sep 17, 2019

Partners in Time

The concept of a Heaven-mandated partner (daolu) in the journey to seeking the Dao is also convenient in justifying homosexual relationships, or sometimes even interspecies relationships. In addition to the relationship between main characters Wei Ying and Lan Zhan, a significant majority of the secondary characters in Modao Zushi are also in homosexual relationships, with heterosexual relationships relegated to marginal characters. (Characters of the elder generation, who are parents or grandparents, are all portrayed as being in heterosexual unions.)

In the visual adaptations of the novel, certain parts of the original story had to be removed or altered in order to jump censorship hurdles. The audio drama, by comparison, is a fairly accurate representation of the novel, including some of the original’s more sensitive aspects and adult content.

One of the most fascinating things about Modao Zushi and its various adaptations are what elements, either magical or sexual, actually make it onto the screen. There is a very fine line to toe between presenting an intense homosocial relationship versus a subtle homosexual relationship. While not all Daoist magic online novels or their visual adaptations feature homosexual relationships, those that do, portray both male characters as equal in competence. For example, Wei Ying and Lan Zhan are equally skilled in their swordsmanship, and one has never been able to defeat the other.

Daoist magic has therefore become one of the main vehicles in telling romantic tales, especially non-traditional love stories. But as recent events surrounding Xiao Zhan and The Untamed reveal, the genre is still not immune from censorship.