Club Seen shines a light on the artists, VJs, and designers providing a visual dimension to after-hours underground culture in urban China.

35-year-old visual artist and animator Miao Jing was born in the megacity of Chongqing and raised in a local cotton mill factory community compound, where he could have easily inherited his parents’ jobs as factory workers. It was in that compound, however, that he first saw oil paintings from a neighbor, setting him on a very different path.

It’s clear that Chongqing’s unique cityscape has left a mark in Miao’s work — there is a similar sense of vertical abundance running through it. His other influences, if not obsessions, range from ancient Egyptian myth to Classical architecture.

These myriad influences blend most seamlessly in 初·ZPTPJ, an audio-visual performance project created by Miao Jing and composer/sound designer Jason Hou. This is how they define it:

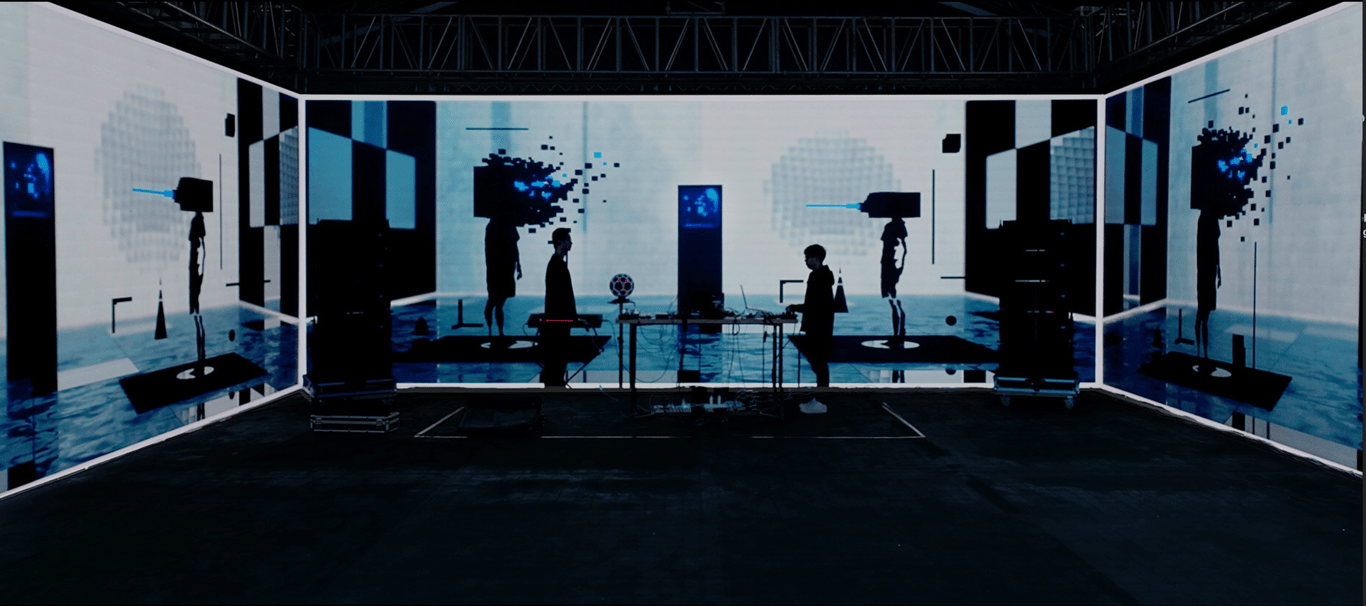

“「初·ZPTPJ」 is a multi-chapter show unveiling the rise and fall of a simulated civilization that reflects our own reality. It questions whether we are a species with amnesia and wonders where humanity is heading at the verge of technological singularity. Miao and Jason perform this story as two archivists of records, extracting audiovisual information on the stage. They strive to develop their ‘primal-futuristic’ style of audiovisual language to provide the audience an immersive experience, transporting them to an alternate reality.”

Miao and Hou have taken ZPTPJ across and outside of China, performing this immersive audiovisual opus in prominent underground clubs such as ALL in Shanghai, Nu Space in Chengdu and Nuts in Chongqing, as well as at seminal San Francisco theater Gray Area.

To dig behind the dazzling and dense imagery, RADII caught up with Miao for a talk about his creative process, how ancient myth influences his art, and how overseas audiences have responded to his work.

RADII: How did you first become interested in making art? Did your parents support you in this, and did you have access to resources to study art in Chongqing growing up?

Miao Jing: It was in the winter when I was 12 years old, one of my neighbors had just graduated from the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. He was arranging his paintings outside his home, and I immediately became very interested. After that, he showed me many books of contemporary art. My parents are both workers. I was born and raised in a large factory community compound. This large compound had everything — one can do everything inside the compound, from birth (there’s a local nursery) to work (assignment of work or inheritance of parents’ jobs).

I started to learn to do oil painting before I started to formally learn the basics of painting. In this way, I accidentally skipped the process of sketch and perspective in basic painting, and went straight into a more creative state. A close friend who was much older was already at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. He “dumped” brushes and paints on me, and I started to make oil paintings. The techniques in oil painting have always influenced my current digital creation.

In 2005, I learned about VJing for the first time with some musician friends, and I started to listen to a lot of dance music, joined the dance party scene, and started to learn to design materials and then VJ. This experience was particularly important.

Miao Jing – [忘] Amnesia

There is a structure of mountains and waters, and the concept of upper, middle, and lower city, which is what Chongqing people call “upper half town, midtown, lower half town.” So I especially like the change and composition of space.

Chongqing is known by many people as a wanghong [网红; internet celebrity] city in recent years thanks to livestreaming apps like Douyin and Kuaishou. This is just a new Chongqing landscape, the new mountain city. It is so, so different from what it was when I was growing up, and many places from the memories of my youth are gone. Shibati, Zhongxing Road, and even Chaotianmen — these cultural landmarks that actually carry the unique “mountain city” characteristics have been replaced by skyscrapers, bizarre architecture and commercial compounds without even leaving a trace behind. We’re only left with the basic frame structure, the mountains and the rivers.

Miao Jing – [忘] Amnesia

Globalization is making every city in the world more and more the same. What I actually want to express in my works is the composition of primitive culture beyond the landscape and the ethnography brought about by this regional culture.

What is the meaning of the name of your studio, Hibanana, which you co-founded with your partner Liu Chang?

When I was VJing in Chengdu in 2008, I was called VJ Banana. Now looking back, it was a rather youthful time when it was easy to feel relaxed and happy. Friends on the dancefloor would get excited to greet the DJ and VJ when they heard music they liked or saw visuals they liked. They would give me a thumbs up and say, “Hi, Banana!” So when Liu Chang and I decided to start a visual studio after that, we got the name Hibanana. Later, when this name was used to register a company in the US, we were jokingly asked if it was a tech company, because it seems that tech companies often use fruits as names.

Miao Jing – 隔江山色 Hills Beyond a River

Can you talk about your creative process? How much time do you spend in pre-production vs production and post-production? How do you balance creative and technical elements in your work?

First of all, “what” is more important than “how” — this is something that I was very sure about from the beginning. Generally speaking, there are three stages of creation. The first stage is setting the theme — what do I want to do? I usually complete this process in my notebook. I note down fragments of text, graphics, drawings, and basically only I can understand these sketches.

The second stage determines the production method and timeline, as well as the cost. This stage will take longer because I don’t like doing repetitive things. I hope that there can be a breakthrough every time I create something new, so I tend to wear myself out. The third stage is the post stage. The post stage is not only the production of the work — I also need to plan how to launch it. This is more fun. Recently, I always feel like I am a “product manager” doing R&D!

My current works basically take at least six months to make. For my new work I’ve upgraded it to a conceptual approach, which allows me to explore a theme in depth. I’m a “newbie” in a circle that only talks about tech, but I’m an “expert” in a circle that only talks about creative!

Miao Jing – 隔江山色 Hills Beyond a River

Myth is an important component of your work. The name ZPTPJ — your live A/V collaboration with Jason Hou — comes from the golden era called “Zep Tepi” in Egyptian mythology. Meanwhile the Chinese names and descriptions for each chapter of this project read like poetic, ancient Chinese sci-fi. You seem to draw from both Western and Eastern references here. What role do you think myth plays in contemporary society? How does ancient myth influence your own, futuristic works?

In [Yuval Noah Harari’s book] A Brief History of Tomorrow, a chapter on the power of fiction illustrates this problem: “The power of the human cooperative network depends on the delicate balance between reality and fiction. Too distorted reality will weaken the power and make you less capable than those who can see the reality; but to effectively strengthen the organizational strength, you still have to rely on those fictional myths.” The concept of “primitive futurism” has always influenced the aesthetic development of my works.

In the description of 初·ZPTPJ you refer to the project as a “‘primal-futuristic’ style of audiovisual language.” What do you mean by this? What do you contribute to this language visually?

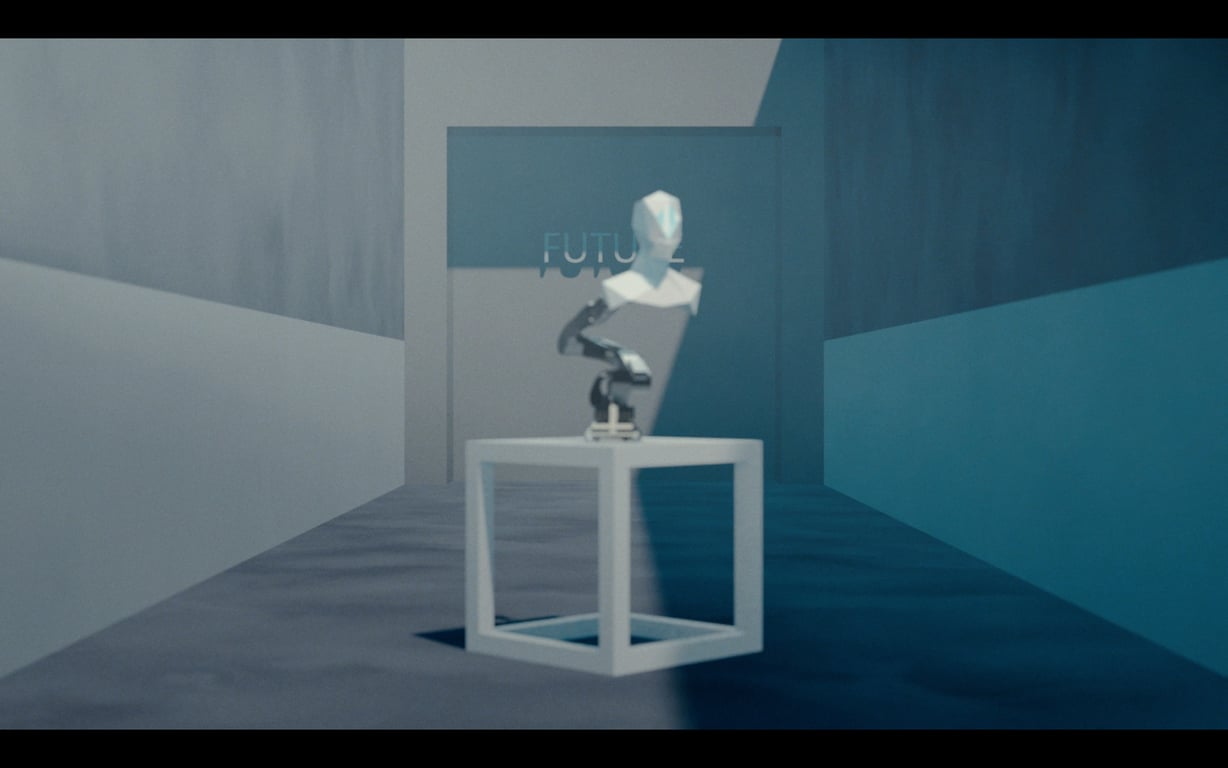

The concept of “Primitive-Futurism” influences the development of our aesthetics. We deliberately look for those “extra futuristic” aesthetic references from past documents and materials. You will find them both familiar and strange — there is a powerful energy that tells us we’ve seen them somewhere.

Another description of 初·ZPTPJ is that it’s “an experiential project at a future museum,” and that you and Jason are the “archivists of records, extracting audiovisual information.” I find this interesting as I understand you’re a frequent museum-goer. Does that speak to your view on the arts in general — that all artworks are archived information for future human (or post-human) audiences to ponder?

I especially like to go to the museums that were made in the Classical period. I am quite obsessed with the textures and the classifications of spaces, but this kind of browsing is limited and it is not easy to save. After digital archiving, it can be shared with audiences all over the world at the same time, and will also be easy to save for future “humans.”

What is the ideal exhibition environment for your work? 初·ZPTPJ is a strictly live performance project, and only a fraction of it can be found online. How does the platform or venue for exhibiting your work affect your creative process?

I accept both online and offline exhibitions. Offline exhibitions are more professional and regulated, the exhibitions are more intuitive, and it is easier for the audience to experience the work in person. It’s too easy for online exhibitions to become a traffic-oriented product — this probably takes more time to develop the technical experience.

The version of ZPTP that you’ve seen is ZPTPJ1.0. Our initial plan was hoping that the audience could come and watch the show offline. An online showcase would dissolve that experience.

You toured with Jason pretty widely in 2018 and 2019 — what venues in and outside of China are best suited to your visual style? How do you prepare your set differently for theaters and clubs?

Because it is an audiovisual performance, the venue must have a professional LED screen or projection screen and sound system. We did the tour in theaters, museums, galleries, live houses, outdoor music festivals. The equipment at domestic venues was all very good, but unfortunately they’re not used to their full potentials. Equipment is pretty standard in foreign venues, but the staff will optimize them to provide us with maximum power — the main thing is that they understand what we are doing.

ZPTPJ1.0 has done 16 shows so far, and we update the details and adjust the structural logic for each show. For now, this version does not arrange content for a specific space. However, we have started planning a new, upgraded version 2.0.

Miao Jing – [忘] Amnesia

We participated in the Currents New Media Art Festival in 2017, when an audiovisual installation Transition was showing, and I invited Jason to design the sound. At the end of 2018, their curator saw our new project and was quite interested, and invited us to participate in the opening performance of their 2019 art festival.

The performance at Gray Area was a project co-curated by Liu Chang and curator Qianqian Ye called “Other Future,” which aims to invite several groups of performing artists to discuss other possibilities of “the future” together. The performances we did abroad have been very good. First of all, during the show, no one under the stage was holding their phones, no one was chatting — people just sat on the floor and focused on the experience of our performance. After the show, many viewers would communicate with us and tell us their thoughts and suggestions. This was effective communication, more than just being cool.

One of your more recent directorial works, 知我仪式, is a cinematic music video for musician Zhang Xiaohou. The video was directed by you and produced by Shanghai-based Atomic Visual Studio. How did you connect with Atomic? How did you decide on this aesthetic for the MV?

This collaboration was the first time I’d worked in a company office since I started working, and the whole process was particularly smooth and delightful! The first time I heard about the music, I was quite clear on the mood the musician wanted to express. This may be because I’d been studying some works on religious belief in recent years.

Atomic’s founder Wang Meng and I have known each other since very early on. In July 2019, he invited Jason and I to participate in their “AV Party” project, doing four performances in Shanghai’s Changjiang Theater. It was completely immersive, with the performers in the middle and audience sitting around the stage, backed by huge projection walls on all four sides. I think this sense of ritual and context is also important to the performers.

What are you working on now? Any future plans in 2020 to collaborate with Jason or other musicians/DJs? Anything else you want to add?

We’re working on the creative planning for ZPTPJ 2.0. The rest of the time I’m focused on the creative development of a new project. I’ve invited new partners to join me on this project, they’re based in US. We’re currently in the character design phase, which is both exciting and challenging. Stay tuned!