As we round off this month’s theme of Health Is Wealth, we’re turning to a must-have book for anyone with a passion for traditional Chinese medicine, as well as those who enjoy visual design. Titled Hong Kong Apothecary: A Visual History of Chinese Medicine Packaging by photojournalist Simon Go, the 199-page book offers a richly illustrated survey of Hong Kong medicine labels, shops, and packaging from the mid-19th to 20th century. Go’s book documents how printing, design, and commercial culture shaped what remedies looked like back then—and who, why, and how they were sold.

In particular, we wanted to look at a chapter titled “Medicine for Women: Women! What Great Strides They Have Made!,” which chronicles a sample of products and packaging from a time when changing ideas about womanhood coexisted with one another—from feudal expectations of motherhood to the rise of cosmetic and health goods marketed to an increasingly independent female consumer. Common packaging examples often centered on women’s reproductive health, focusing on remedies that claimed to prevent ailments associated with menstrual irregularities and conditions arising during prenatal and postnatal stages.

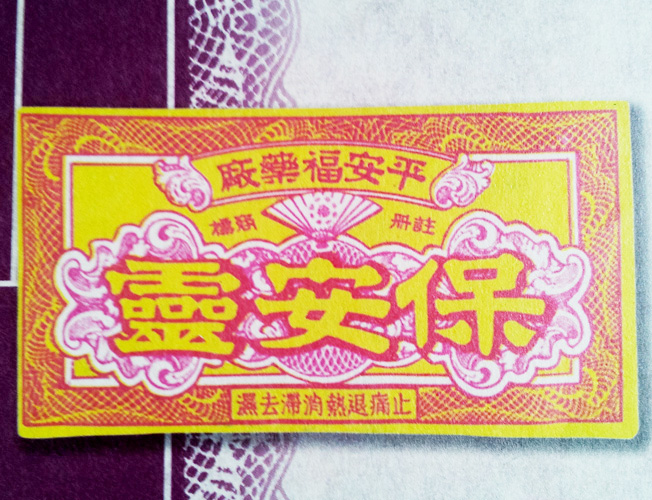

Tak Fat Pharmacy’s claim that “nine out of ten women suffer from leukorrhea” was “perhaps exaggerated,” Go notes in his book. Yet the statistic does reflect how common the “problem” was. Leukorrhea refers to vaginal discharge, typically odorless and colorless. According to a packet of the company’s lap chi bak dai yun (白帶丸), which are pills taken for the instant treatment of leukorrhea, “the heart controls the flow of blood, so menstrual bleeding should be reddish in color. If periods become irregular, the redness of menstrual blood will easily alter. If blood turns purplish and coagulates, it indicates menstrual disorders.”

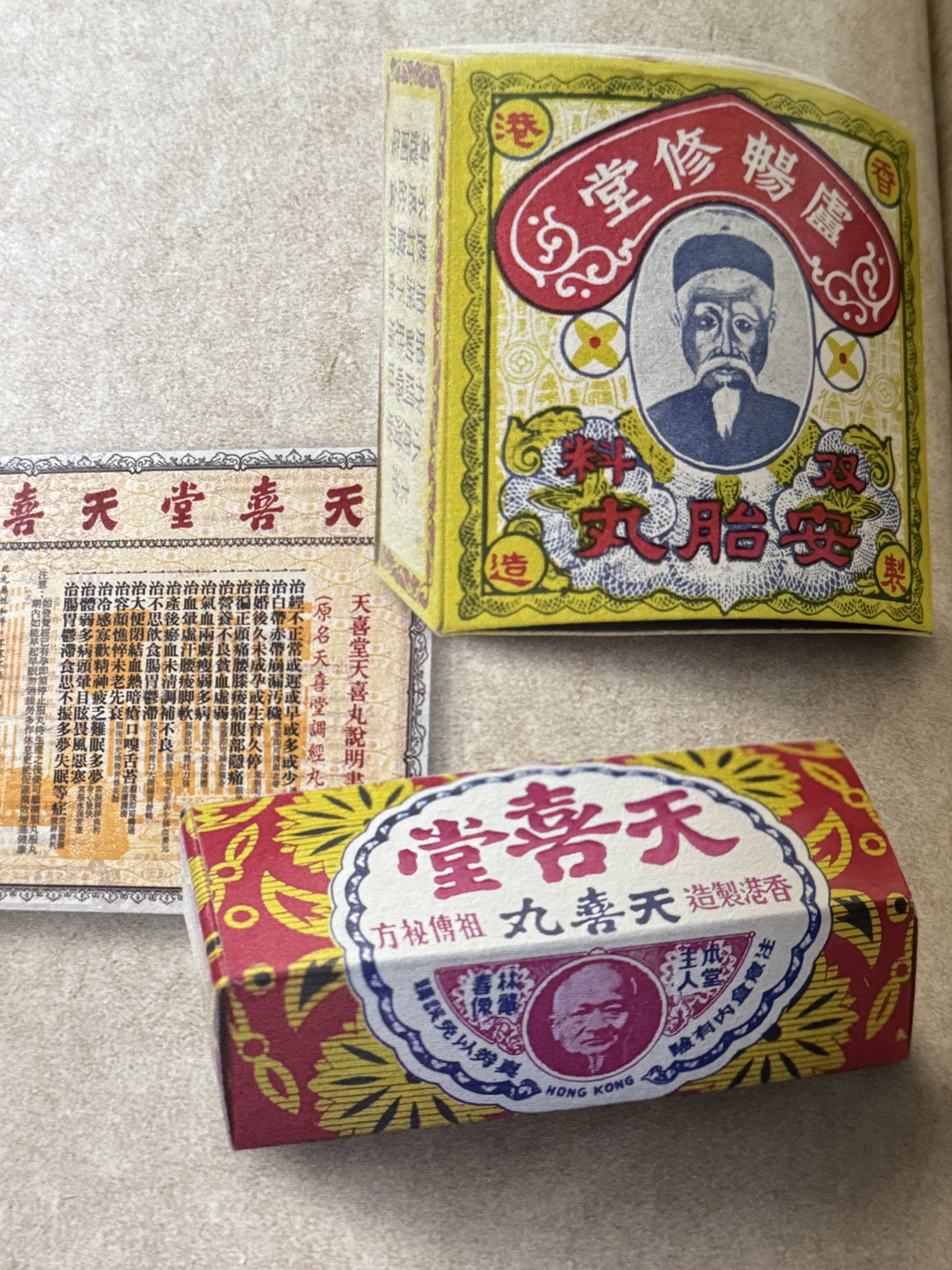

On Toi pills (安胎丸) were primarily marketed toward expectant mothers, formulated to alleviate fetal movement, discomfort, and abdominal pain, while also claiming to prevent bleeding during pregnancy and reduce the risk of miscarriage. The product reveals how early pharmaceutical brands tapped into maternal fears and expectations, framing traditional medicine as both comfort and cure. In many ways, pills like these captured the tension between care and commerce, selling reassurance to women navigating the uncertainties of pregnancy in a rapidly modernizing Hong Kong.

However, as societal expectations gradually shifted and women’s suffrage efforts became more widely accepted, women’s social status rose, and reproduction was no longer their raison d’être. As Go notes, “Paying attention to one’s appearance, and enjoying and satisfying sex life were among the modern woman’s chief preoccupations.” As a result, a new and significant target audience for advertisers emerged.

The fear of aging prematurely was a constant whisper in the background of women’s lives, and among these, Pak Foong pills (白鳳丸) stood out—marketed with the dual promise of “preserving youthfulness and increasing vitality.” Positioned as an all-in-one solution for women’s wellness, they claimed to regulate menstruation, boost energy, and restore radiance. Beyond their herbal formula, the pills symbolized a larger cultural fixation on eternal youth—selling not just medicine, but the “dream of timeless femininity.”

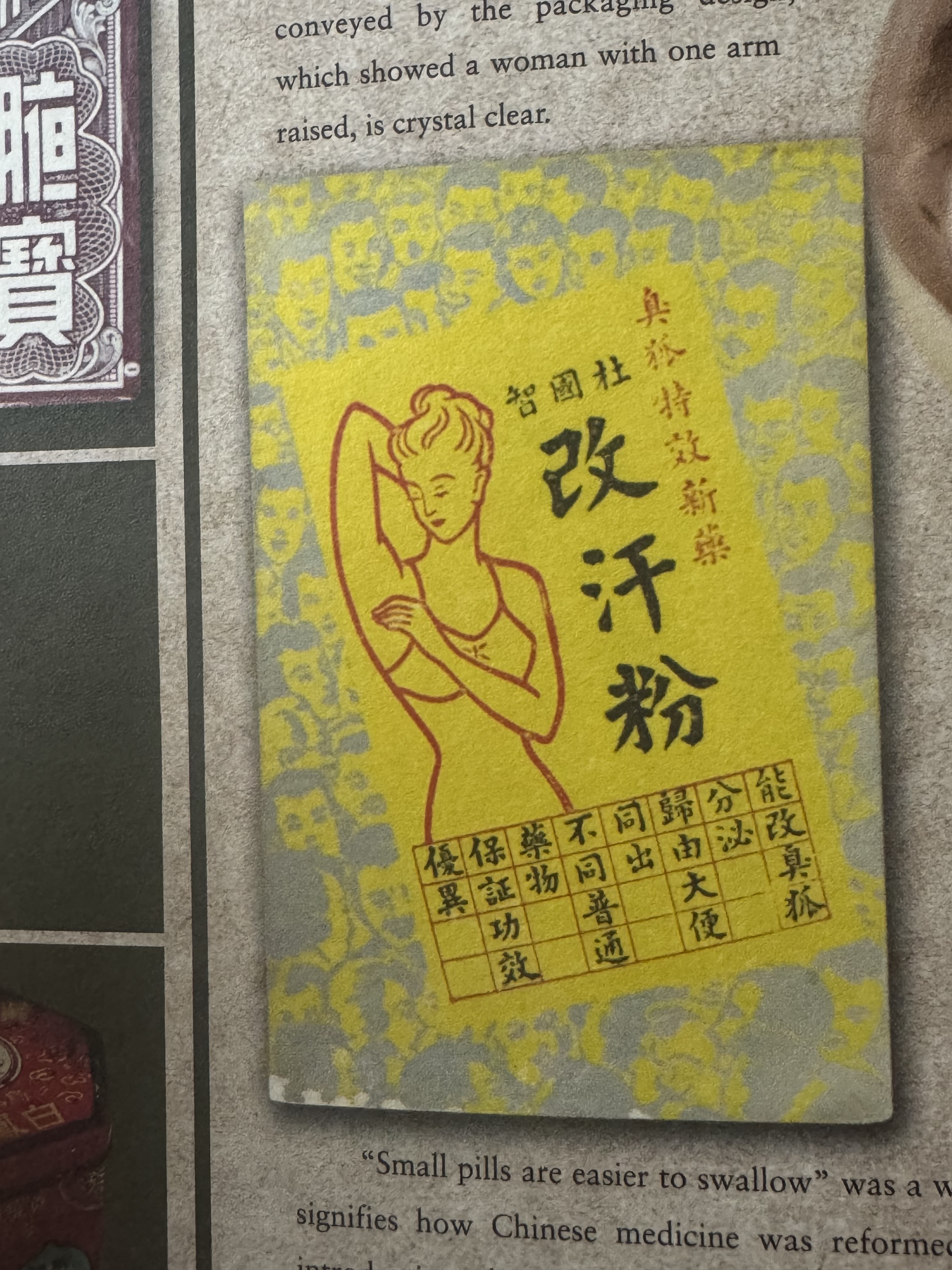

As an earthy local saying puts it, “Men stink, and women are fragrant!” The phrase summed up a time when femininity was as much about appearance as it was about composure. To meet that social expectation, pharmaceutical manufacturers launched products like Ban Bo and Yik Boo, antiperspirant deodorants marketed specifically to women. Packaged in blue and yellow, depicting a woman raising one arm, they promised to keep the body cool and odor-free. More than simple hygiene products, they reflected how advertising of the time fused modern self-care with traditional ideals of womanly refinement—and the performance of being effortlessly fragrant.

Taken together, Go’s book examines these packages—whether promising beauty, fertility, or freshness—offering a snapshot into how medicine, marketing, and modern womanhood intertwined in colonial Hong Kong. Medicine, particularly these examples, was more than just pills and powders, but rather solutions and stories printed in color and type. Go’s collection of labels traces how, in this particular chapter, women’s bodies became both consumers and commodities in a world of rapid change.

All images scanned via Hong Kong Apothecary: A Visual History of Chinese Medicine Packaging.