China’s Digital Renaissance is a series exploring new currents in Chinese contemporary art, created in partnership with East West Bank. In this article, we explore the digital restoration, preservation. and appreciation of Buddhist grotto art.

As I step into the vast Yungang Buddhist grottoes, the outside world fades away, and is replaced by an atmosphere of stillness and reverence. Inside, the air feels cool and calm, offering respite from the bustling city in the distance.

Looking up, I’m awestruck by the smooth, serene face of a monumental Buddha statue. The delicate holes scattered across its surface are evidence of past restoration efforts. In this moment, I am humbled by the weight of history, a legacy spanning millennia.

China is home to many other remarkable Buddhist caves, apart from the Yungang grottoes, whose works are now experiencing an influx of public interest.

A simple search on Xiaohongshu, a popular Chinese social media platform similar to Instagram, reveals a remarkable surge in posts related to “Dunhuangology,” the academic study of the city of Dunhuang and its renowned Mogao Caves. The younger generation, particularly Gen Z creators and consumers, is quickly developing a deep interest when it comes to Buddhist paintings and sites.

A growing interest among young netizens speaks to the enduring appeal of these cave artworks.

However, these exquisite Buddhist caves are exceptionally vulnerable to sand erosion, climate change, and human activity. In the early ’90s, when people began to realize the urgency of the issue, a series of preservation and digitization efforts started to emerge.

Conversations with academics, artists, and cultural enthusiasts all offer different insights into the constantly-evolving techniques used to preserve and share the traditions of Buddhist grotto art.

Dunhuang’s Digital Library

One key figure in this preservation movement is archaeologist Fan Jinshi, warmly known as the “daughter of Dunhuang.”

Fan is the former director of the Dunhuang Research Academy, where she spearheaded initiatives to preserve and digitally document the artistic treasures of the Mogao Caves.

The Dunhuang Research Academy was established in 1944 to study and oversee the caves. However, it wasn’t until 1979 that the caves opened to the general public, attracting 26,000 visitors in their inaugural year.

Fan, who joined the Academy immediately after graduating, witnessed firsthand the complex interplay between tourism and preservation.

In 1994, two years after Microsoft entered the Chinese market, Fan initiated a digitization effort. The endeavor involved creating a comprehensive digital archive of the caves, which granted the global public unprecedented virtual access to the sacred site.

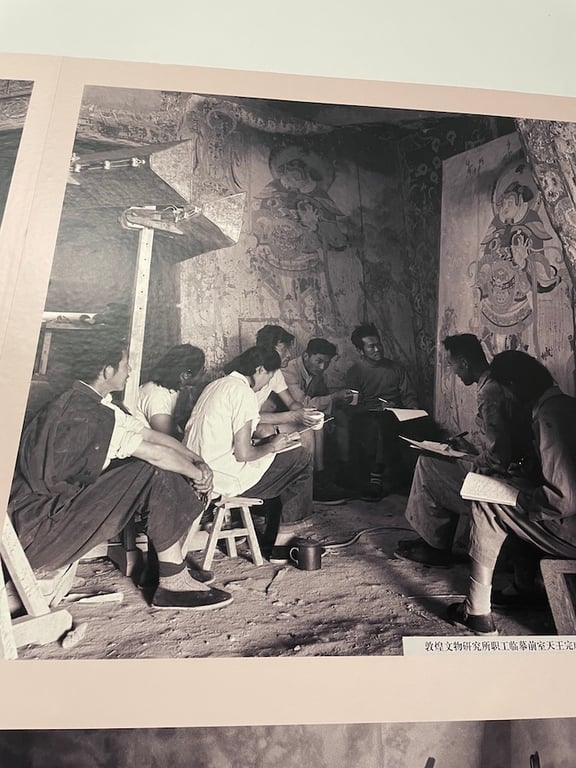

Photographer Wu Jian is a member of Fan’s digitization team, and has been capturing the essence of Dunhuang’s grottoes for over two decades.

In a previous interview with state-run China News Network, Wu recalled that in the early days, the team had relied on film photography, painstakingly capturing specific points within the caves and stitching them together by hand.

Later, digital cameras were one of the first game-changers for Wu and his colleagues, offering significant improvements in both quality and efficiency.

Fast forward to today, and experts can use this library to remotely restore the caves, produce high-definition prints, and reproduce colored sculptures through 3D scanning.

The comprehensive collection of data and images in the archive even allows the team to predict how effective different restoration techniques will be. The video below shows a few of the available approaches.

Recently, the team at the Dunhuang Research Academy brought their show on the road.

An exhibition titled The Trace of Civilization appeared at the Beijing Minsheng Art Museum last September, featuring eight replica caves meticulously crafted by generations of Dunhuang researchers over a span of 70 years.

Despite the intricate detailing and impressive quality of these replicas, some visitors dismissed their significance, labeling them as mere “fakes.”

The reaction highlights the need to bridge the gap between the general public’s understanding of these replicas, and the field of thought and research behind them. There’s a balance to be found between curating replicas or digital art in museums, and preserving the original on-site works.

The Challenge of Showcasing Grotto Art

Zhang Zixuan is part of China’s post-’90s generation, who are becoming increasingly interested in the art of these ancient grottoes.

“It’s nearly impossible to understand the art just by reading the introductions,” Zhang remarked after seeing The Trace of Civilization. “I followed three tour guides throughout the day, and they all told really engaging stories that brought the work to life.”

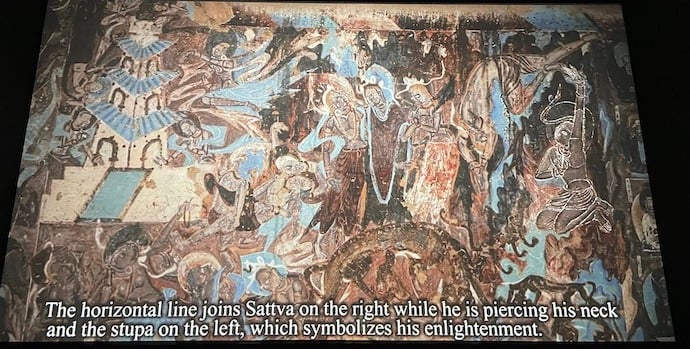

Zhang says that the mural art shown above is her favorite piece from the exhibition. It depicts a jātaka — a traditional tale about the Buddha’s past lives — of a nine-colored deer.

The story goes that a deer saved a man from drowning, but the man later betrayed the deer by revealing its location to the king. The deer exposes the man’s treachery, leading the king to offer his royal protection. Subsequently, the ungrateful man suffers from painful sores all over his body as punishment for his betrayal.

It’s just one example of the sprawling, diverse narratives and worldviews encompassed within these Buddhist cave traditions.

“The moral lesson conveyed in the mural is rather straightforward: ‘good begets good, evil begets evil,’” Zhang recalled. Inspired by her encounter, she plans to conduct further cultural research for her upcoming trip to Dunhuang.

Marketing these Buddhist displays presents a real challenge. A veteran organizer, Mrs. Li, who requested anonymity, shared her frustrations in navigating the bureaucratic hurdles associated with such exhibitions.

According to Li, obtaining approval from top management becomes necessary when certain themes come into play.

“Gatekeepers prioritize safety, both in terms of physical safety for visitors, and the need to avoid potential religious controversies,” says Li. “So we had to shift the language in our promotional materials, from Buddhist teachings to the common legacy of humanity,” she shares, aligning with the state’s current vision of “building a human community with a shared future for mankind.”

Li is dedicated to promoting the essence of Buddhist art, and jokingly described the negotiation and lobbying process as huayuan, the traditional term for a monk begging alms.

Despite the challenges, Li remains optimistic about the future of grotto art in China, emphasizing the importance of preserving and promoting these cultural treasures.

She’s not alone in that sentiment — the preservation and promotion of grotto art is even included in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan, which kicked off in 2021.

Reviving Buddhist Art in the Digital Age

Outside of established cultural institutions, a new wave of young digital artists is making a mark with their own interpretations of Buddhist art.

Song Ting, a Chinese AI artist and NFT creator who comes from a family of classical academics, is naturally drawn to traditional art. Having majored in classic Chinese literature at Tsinghua University, Song’s undergraduate thesis delved into proofreading and annotating Dunhuang dance scores, documenting choreography and musical accompaniment for traditional dances from the Dunhuang region.

Building upon this foundation, her series titled Supplement is a continuation of her work that engages with themes of traditional art. By inputting thousands of images from the Artbreeder database into a computer, her human-AI collaborative NFT ties together themes that are both ancient and new, Eastern and Western.

Supplement I injects electronic dance music into the Buddhist scene, Supplement II puts Beethoven side-by-side with traditional deities, while Supplement III depicts a dancer smashing an orange into a carpet.

Accompanying Supplement I is a soundtrack composed by musician Isen Jason, which incorporates traditional instruments from various countries, as well as vocal samples from minority ethnic groups.

When the video reaches its climax, a female voice announces “conversion succeeded,” and the beat drops, ushering in the video’s second half. It’s just one example of a trend that sees young Chinese artists intentionally obscuring the lines of cultural influence.

“As an early adopter of AI and blockchain technology, I believe these technologies exist beyond national or temporal confines, offering a humanities student like me an opportunity to make up historical regrets that cannot be repeated.”

“As an early adopter of AI and blockchain technology, I believe these technologies exist beyond national or temporal confines, offering a humanities student like me an opportunity to make up for historical regrets,” Song reflects.

In each generation’s interaction with Buddhist art, a unique rendition of Buddha emerges. These grotto artworks represent an unending process of revision and evolution, and over the centuries, countless artists have added their own layers.

Today, the nature of those layers may be changing, but a new generation of artists, academics, and appreciators is clearly keeping the tradition alive.

Cover image designed by Haedi Yue. All images via the author.