It’s probably difficult nowadays to picture a Shanghai where Esperanto is spoken in lieu of Mandarin Chinese, but that was a future that some Chinese radicals had once envisioned.

Today, the constructed language of Esperanto is likely unknown to most young Chinese people, but the country is home to one of the world’s few Esperanto radio stations, publications, and museums. Esperanto has a long, complicated history in China, leaving it an active present-day community.

It was 1887 when Ludovic L. Zamenhof, a Polish linguist, published a booklet envisioning an international language under the pen name Doktoro Esperanto (literally, the one who hopes). The constructed language — soon to be known as Esperanto — focused on simplicity, with few grammatical rules, genderless nouns, and uninflected verbs. Its vocabulary, too, is largely based on other European languages.

His project quickly gained interest across Europe, and it only took a few short years for the first Esperanto societies to emerge in Russia and France — and eventually it was brought to China at the turn of the twentieth century as the country searched for its own path to modernization.

Anarchism and Chinese liberation

Zamenhof was raised during the Russian occupation of Poland, where he witnessed ethno-linguistic tensions and saw his politically neutral language — designed as a common second language, against the hegemony of any dominant group — as the remedy. It was for that reason Esperanto gained popularity among anarchists and socialists who saw the project as a vehicle for internationalist movements and revolutionary ambitions.

In the years leading up to the May Fourth Movement in 1919, reformists in the Chinese literati sought to replace classical Chinese in written texts with vernacular Chinese, or baihua, to improve literacy rate. At the same time, Chinese anarchists in Japan, France, and China also debated over the adoption of Esperanto as a national language — as seen in prominent literary magazines including La Jeunesse, founded by Chen Duxiu, as well as the Guofeng Ribao published by the Esperantist Jing Meijiu.

The Republic of China government was, at first, sympathetic to the Esperanto movement. Cai Yuanpei, the Chinese educator who headed the Ministry of Education under the Republic of China government, ordered the nation’s teachers’ colleges to set up Esperanto electives in 1912, before setting up the Beijing Esperanto College in 1923. As the president of Peking University, Cai appointed the Esperantist Sun Guozhang to introduce Esperanto to its official curriculum, later inviting the famous Russian poet Vasilij Erošenko to join the department. A leading Esperantist who sought refuge in China after being expelled from Japan, Erošenko lived with the novelist Lu Xun (in Esperanto, Lusin) and his brother, Zhou Zuoren, also an Esperantist.

Vasilij Eroŝenko (first row, 5th from left) and his Esperanto students in Beijing, along with Zhou Zuoren (first row, 3rd from left) and Lu Xun (first row, 6th from left). Source: Austrian National Library.

In the 1930s, amid internal conflicts over the United Front campaign against Japanese invasion, as well as crackdowns by the Kuomintang, the Chinese anarchist movement began to lose momentum. Ba Jin (in Esperanto, Bakin), the Chengdu-born anarchist writer who had studied in France, attempted to pivot his Esperanto literature away from the political movement in which he was involved, despite criticism from his activist peers. A vast number of Esperantists — including Hu Yuzhi, who would become a politician after the Civil War — also moved away from anarchism to align with the Chinese Communist Party, wanting to use the language to advocate internationally for China’s anti-Japanese resistance and its national liberation. (They were joined by non-Chinese Esperantists, such as the Japanese anti-imperialist Teru Hasegawa, better known by her Esperanto name Verda Majo.)

Enshrined in the way of true revolution

The trajectory of China’s Esperanto movement changed its course after the Communist triumph in 1949. Indeed, the Esperanto community had been largely supportive of the CCP — and its vision aligned well with the new government’s internationalist ideology. In response to the Esperanto association in the Communist stronghold of Yan’an, Mao Zedong wrote in 1939, “If Esperanto is taken as a form and enshrined in the way of true internationalism and the way of true revolution, then Esperanto can be learned and should be learned.”

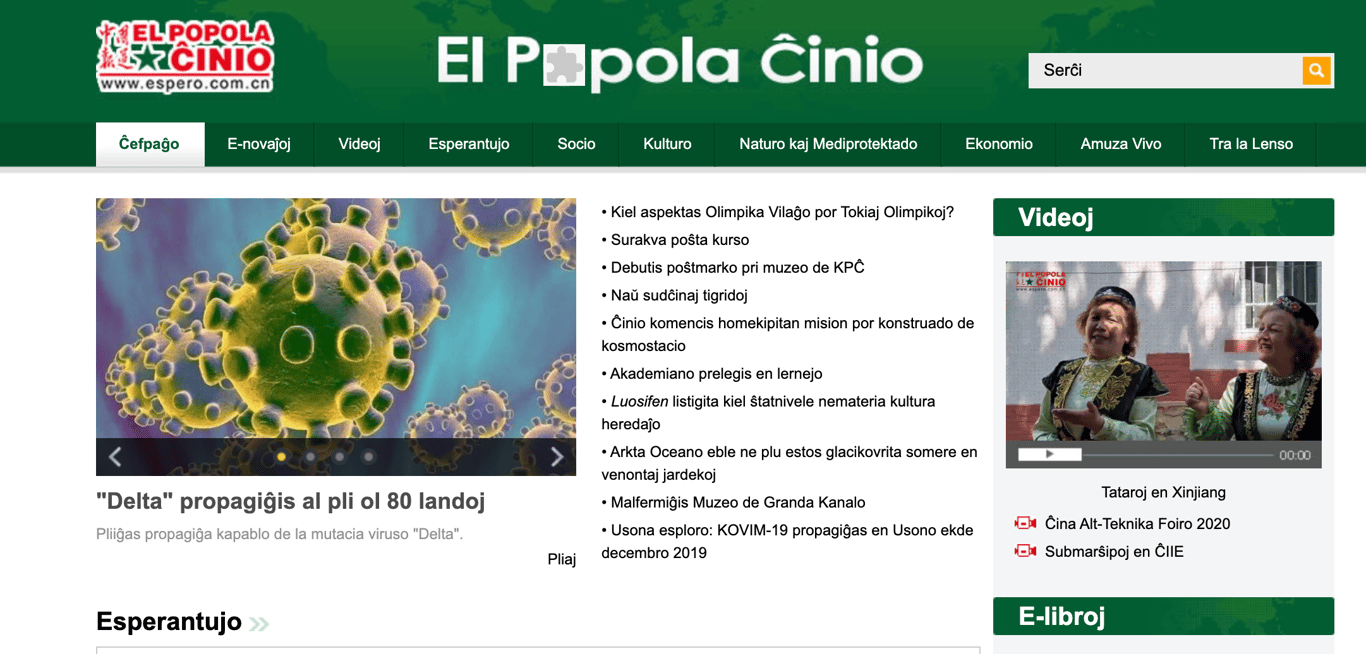

Esperanto associations around the country were allowed to resume their operations, and a national organization, the All-China Esperanto Association (also known as the China Esperanto League), was founded in Beijing in 1951. The PRC’s official Esperanto publication, El Popola Ĉinio (“The People of China”), was founded in 1950 as a monthly magazine. The People’s Republic in the 1950s also sent delegates abroad to attend the Universal Congress, organized by the Universal Esperanto Association; it soon hosted its first national Esperanto work conference in Beijing in 1963.

You might also like:

Is Chinese TV Biased Against Non-Mandarin Music?Recent incidents on iQIYI’s major music variety shows have thrust so-called “dialect music” back into the spotlightArticle Aug 24, 2020

Is Chinese TV Biased Against Non-Mandarin Music?Recent incidents on iQIYI’s major music variety shows have thrust so-called “dialect music” back into the spotlightArticle Aug 24, 2020

Though the PRC never considered adopting Esperanto as the national language, it likely influenced the nation’s standard romanization scheme, Hanyu Pinyin, which was invented by the Esperanto scholar Zhou Youguang.

While the Esperanto community received recognition and support from the state, the movement wasn’t immune from the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. Esperantists were, without doubt, internationalists and revolutionaries — but they were also seen as intellectuals who colluded with foreigners. One prominent Esperanto writer in Tianjin, Armand Su, was labeled as a counterrevolutionary in 1966 and imprisoned until 1979. Zhou was also sent to a labor camp due to his past as a banker in America.

Nevertheless, Esperanto played an important part in the PRC’s global propaganda campaign even during the Cultural Revolution. Under Mao, Beijing was interested in promoting China to the rest of the world — yet in addition to that, it also took an active position to spread Maoist ideologies in the years following the Sino-Soviet split. One of the overseas propaganda vehicles was Radio Peking, which started broadcasting in Esperanto in 1964 — first targeting European listeners before expanding to Asia and Latin America — and was uninterrupted during the Cultural Revolution.

Reform, rebirth

As the Cultural Revolution came to an end in 1976, the Esperanto community of China reconnected with the rest of the world. After Chinese delegates returned to the Universal Congress in 1978, following over a decade’s absence, the Universal Esperanto Association approved China’s application for membership in 1980, and Ba Jin was elected to its honorary committee of patrons. In 1986, China hosted its Universal Congress in Beijing’s western suburbs — and it did again in 2004.

You might also like:

“Cantonese.jpg”: A Boisterous, Cartoon Dictionary of Idioms, Proverbs and SlangThe drawings of Hong Kong cartoonist Ah To are every bit as eccentric and boisterous as the Cantonese expressions they depictArticle Jun 03, 2019

“Cantonese.jpg”: A Boisterous, Cartoon Dictionary of Idioms, Proverbs and SlangThe drawings of Hong Kong cartoonist Ah To are every bit as eccentric and boisterous as the Cantonese expressions they depictArticle Jun 03, 2019

Trezoro Huang Yinbao was a government bureaucrat in the western province of Gansu in the 1980s — when he picked up Esperanto, which he thought was easier to learn than English or Japanese. “That was when China was opening up to the world. People were interested in new things, and learning languages became popular again,” says Huang.

Now based in Xi’an, Chielismo Wang Tianyi also studied Esperanto amid China’s economic reform. “Back then, about a million people attended various Esperanto classes. However, the majority of people have since given up, and I am one of the few remaining learners,” Wang says.

Wang spent decades working in international trade with Esperantists from other countries, and when he retired a few years ago, he opened an online Esperanto bookstore. “Most of the young readers don’t buy books to study Esperanto, because there are many free websites online. Most of the readers are still older Esperanto speakers from the 1980s and 1990s,” he adds.

At its peak, the country had an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 speakers. The Chinese Esperanto League most recently reported 1144 members from China to the Universal Esperanto Association, but no one knows for sure how many Esperanto speakers there are in China today — most didn’t learn it in a school, and younger people are more likely to look for communities online than fill out membership paperwork with an official association.

China has continued its involvement, both grassroot and governmental, in the Esperanto community. El Popola Ĉinio, the PRC’s first official Esperanto magazine, still publishes today online. China Radio International, formerly Radio Peking, is still broadcasting daily in Esperanto to listeners at home and abroad. China.org.cn, a news portal controlled by the State Council, has an Esperanto version. While these publications translate political propaganda as part of their work, they remain an important resource for Esperanto learners in China and elsewhere.

Zaozhuang University in Shandong province established its Esperanto major in 2018 and, perhaps unbeknownst to most residents in the city’s resident, Asia’s first Esperanto museum, back in 2012.

“If China continues to grow, there will likely be a clash between the Chinese and English languages.”

Though the media for transnational community-building are now more accessible than ever, the global linguistic movement has lost much of its momentum. For one, the ideals of internationalism have been overshadowed by the globalization under neoliberalism and the hegemonies it has strengthened. Meanwhile, the premise of using an artificial language to conceal ethnolinguistic differences and power imbalances may not have been fundamentally productive in mitigating such boundaries.

It’s also not that practical to pick up a language that brings material rewards, when another language might create better career opportunities. China may be one of the only countries that offer Esperanto as a university major, but that degree only offers a handful of options in the job market.

Screengrab of ‘s homepage

While the grassroot community struggles, state-led support is in decline. “In the past, China used to have high-level leaders who supported this cause [the Esperanto movement], and the work was smooth,” says Zhao Wenqi, an editor at El Popola Ĉinio, who believes that the support from the state is no longer as strong. “We need to work hard on our own,” he adds.

Huang, the Esperantist from Gansu, knows that Esperanto is no competitor to natural languages, but he believes that the visible, cross-generational community of Esperantists like him will prevent the linguistic project from vanishing anytime soon.

“If China continues to grow, there will likely be a clash between the Chinese and English languages,” he says.

“When that happens, a compromise will be necessary; that’s when Esperanto could be useful.”

Cover image via Unsplash