Sohu is reporting that fifth-generation filmmaker Peng Xiaolian passed away at 10 AM this morning, at age 66. Born in Hunan province in 1953, according to the Sohu report, Peng was part of the storied Beijing Film Academy class of 1982, which also included fellow fifth-generation directors Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou. Much of Peng’s oeuvre, which spans directing, screenwriting and fiction writing, deals with the tumultuous period of the Cultural Revolution and following years.

Her own experience during this time was traumatic. She spent nine years in rural Jiangxi province for countryside re-education, while her mother suffered abuse from Red Guards and her father was beaten to death in 1968.

Peng emerged from this hardship to graduate from the prestigious Beijing Film Academy at a time when Chinese society was becoming increasingly open to outside influence, a period when the ideological strictures of the Mao era were being eased to create opportunities for economic growth. (Mao Zedong died in 1976, and his successor Deng Xiaoping launched a program of economic opening in late 1978.) This enabled writers and directors like Peng to attempt a frank engagement with the tumultuous period during which they came of age, and to address progressive social issues in a way that was not possible for previous generations of filmmakers.

Women’s Story (1988)

Peng joined the Shanghai Film Studio in 1982, and rose to international prominence with the 1988 release of her sophomore film, Women’s Story (女人的故事), which critiques oppressive gender norms from the perspective of three young women living in a small town near the Great Wall of China.

In the wake of this early success, Peng moved to New York in 1989 after being prohibited from making a film about 20th century Chinese novelist Ba Jin in the ideologically tense period of the Tiananmen demonstrations. While in New York, she completed an MFA from New York University.

Peng returned to Shanghai in 1996, where she would spend the rest of her career. The city itself was the subject and backdrop of most of her subsequent work. In a 2005 interview with That’s Shanghai, she said:

Shanghai is like a character in my movies. The culture is so different from the rest of the country. It’s the most interesting, modern and artistic city in China. During the 30s and 40s there were many colonial concessions here. It was – and still is – a multicultural city. It’s like a foreign city in China. That’s why I pay a lot of attention to Shanghai, to its culture and to people who live here.

Peng’s last film, 2017’s Please Remember Me, was featured at the inaugural Pingyao Film Festival launched by sixth-generation director Jia Zhangke that year. Fittingly, her final work provides a meta-critique of the development of Chinese cinema, of which Peng was a driving agent. According to a review in Filmmaker Magazine:

Successfully fusing meta-fiction with documentary, Peng Xiaolian’s film never lapses into didacticism even when stressing the importance of historical awareness for the present and future of Chinese cinema. When Caiyun manages to land a job with a big director by the end of the film, the film’s mood remains (un)equivocally bittersweet, as if wary of what this coveted future in showbiz might bring.

—

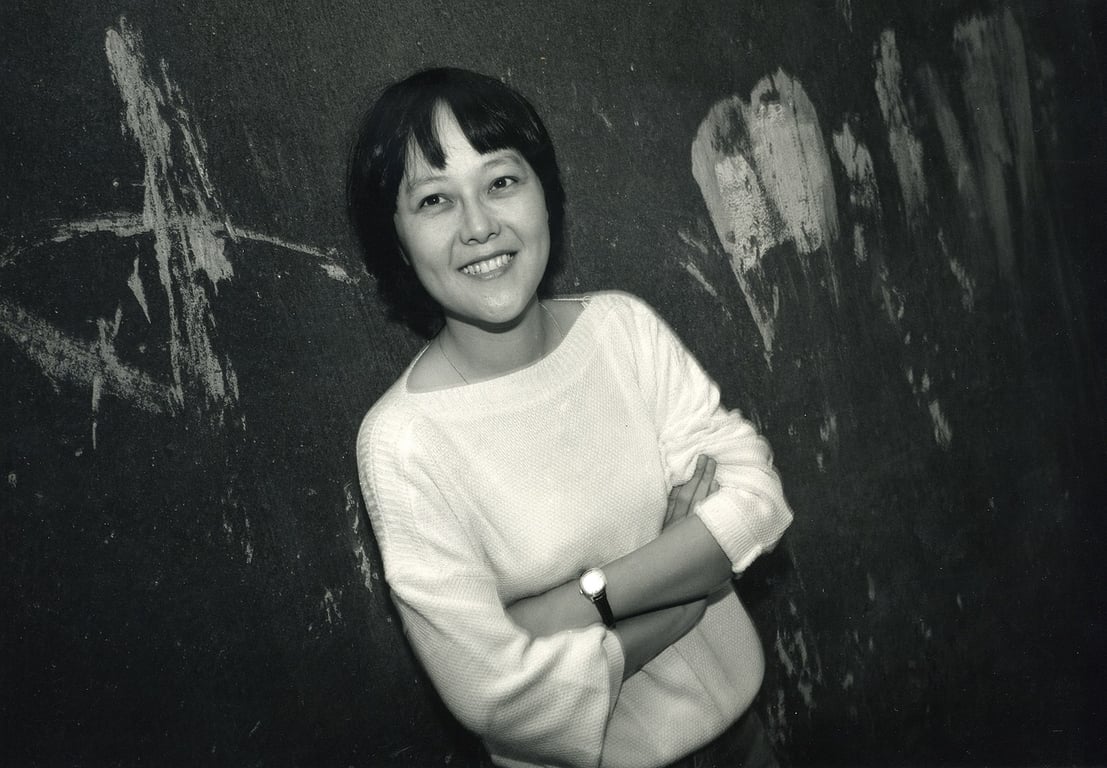

Cover photo: Peng Xiaolian in New York, 1989 (photo by Louisa Wei)

You might also like:

Meet the New Wave of Chinese FilmmakersArticle Aug 02, 2018

Meet the New Wave of Chinese FilmmakersArticle Aug 02, 2018

BRICS Film Co-Production “Half the Sky” Focuses on Women’s StoriesArticle Jun 20, 2018

BRICS Film Co-Production “Half the Sky” Focuses on Women’s StoriesArticle Jun 20, 2018

“These people glide by us every day”: Filmmaker Han Xia on the Impact of Angels Wear WhiteArticle Nov 30, 2017

“These people glide by us every day”: Filmmaker Han Xia on the Impact of Angels Wear WhiteArticle Nov 30, 2017