Meet the New Wave of Chinese Filmmakers

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When talking about mainland Chinese film directors, critics tend to use a six-generation system to categorize them and their work based on shared backgrounds. For some time now, there’s been debate about whether a new generation of directorial talent is emerging in such an easily identifiable way.

But whether or not they slot into a clearly defined generational tag, it’s clear there are some very exciting young talents coming out of China right now. Below, we’ve picked out some of the key names to watch, but first, a quick run-through of the preceding “generations”.

THE SIX GENERATIONS OF CHINESE FILM

Beginning with a 1905 recording of a Peking Opera performance, The Battle of Dingjunshan, the first generation centered around Shanghai and culminated in the first “golden period” of Chinese cinema in the 1930s, before the Japanese invasion. The second generation, including filmmakers Cai Chusheng (Spring River Flows East, 1947) and Fei Mu (Spring in a Small Town, 1948), focused on society and people’s post-WWII mindset, and is considered one of the most influential periods of Chinese film history.

Making it through the Cultural Revolution, the third generation aimed to reveal the conflicts and paradoxes of life, with Xie Jin’s Hibiscus Town being a representative sample. The fourth generation are mainly directors who graduated from the Beijing Film Academy (BFA) in the 1960s, and focused on life in the countryside — which many of them experienced firsthand as “sent-down youth.”

Related:

The fifth generation is full of big names that even a casual film buff might know: Zhang Yimou (Red Sorghum, 1987; Hero, 2003), Chen Kaige (Farewell My Concubine, 1993), Tian Zhuangzhuang (The Blue Kite, 1993). Getting their training at BFA during the 1980s, the fifth generation was eager to try new methods and seek creative perspectives in an economically opening China. In recent years, many of them have opted toward big-budget films with A-list casts.

Just as accomplished is the sixth generation, also called the “urban generation,” which overall makes movies more quickly and cheaply, and has a stronger connection to an independent filmmaking tradition. Long takes, hand-held cameras, and documentary-like narratives are used in many of their films to show the margins of modern Chinese life. Jia Zhangke (Still Life, 2006; A Touch of Sin, 2013), Lou Ye (Suzhou River, 2000; Summer Palace, 2006), Wang Xiaoshuai (Beijing Bicycle, 2001; Shanghai Dreams, 2005) and Zhang Yuan (Beijing Bastards, 1993; East Palace, West Palace, 1997) have all received international acclaim.

Related:

While fifth- and sixth-generation directors are still active in the film scene, a “seventh generation” of Chinese filmmakers has not been commonly acknowledged yet. Sixth-generation director Wang Xiaoshuai even predicted (link in Chinese) in 2010 that:

In the information era, young people are knowledgeable, but not necessarily literate, so ‘the seventh generation director’ will not appear… Nowadays directors’ personalities are emphasized more and more, which means a common, group characteristic has vanished, so a ‘seventh generation’ is not likely to form at all. Without any similarity, it is meaningless to categorize young directors into the seventh or the eighth, if only based on age or graduation year.

He may have a point, but a more important question might be: Regardless of whether or not there is a “seventh generation,” who are the emerging directors that we should keep an eye on today?

Luckily, WeChat film account 一起拍电影YIQIPAIDIANYING recently put together a list of the top 50 young Chinese directors, which might give us some clues. All of the filmmakers on the list were born after 1980, and the ranking is based on their films’ box office performance, rating on popular review site Douban, and index on search engine Baidu, which shows their online influence.

The diverse constitution of this list reveals that a huge change in the Chinese film industry is underway.

Let’s break the list down into some meaningful categories:

COMMERCIAL BLOCKBUSTERS

It’s not surprising that Wen Muye took the #1 spot. The 33-year-old director’s first feature film, Dying To Survive, has taken in 3 billion RMB (over 440 million USD) at the box office so far, and has been a critical smash hit.

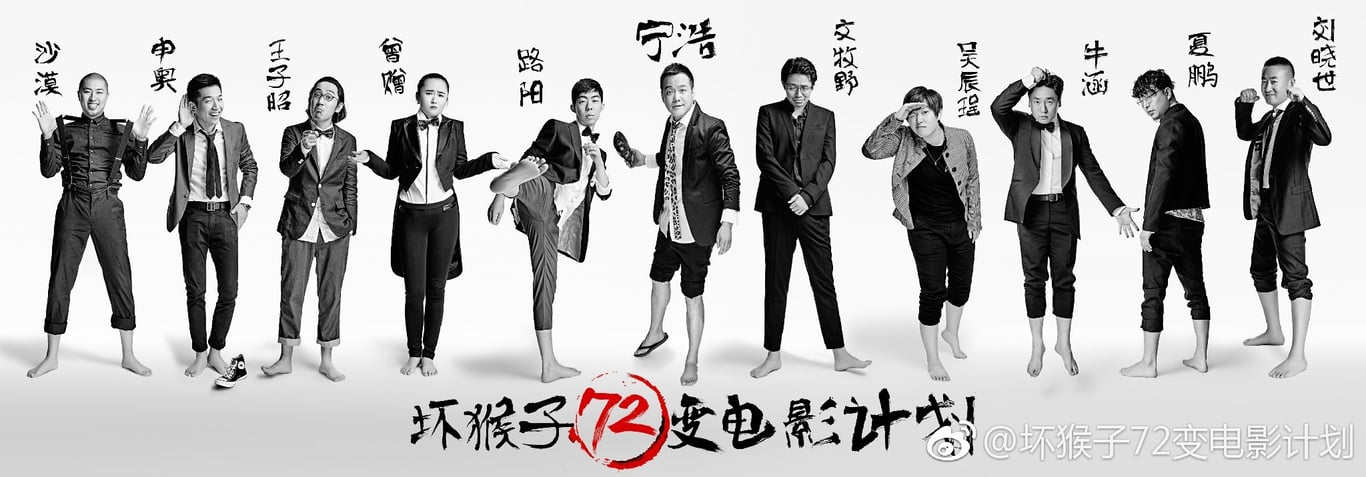

The film was part of a development plan called the 72-Transformation Film Plan, initiated by Dirty Monkeys Studio in 2016 with the goal of helping new directors produce their early works. Lu Yang, another director included in the plan, reached #7 on the list for his martial arts film Brotherhood of Blades II: The Infernal Battlefield.

Middle three from left to right: Lu Yang; Dirty Monkey Studios founder Ning Hao; Wen Muye

Another powerful group is comprised of the directors and screenwriters signed with Fun Age Pictures, the film production sector of Muahua Fun Age (开心麻花). Their original adaptation of comedic play Goodbye Mr. Loser, directed by the duo of Yan Fei and Peng Damo (together #4 on the list), became the biggest box office black horse in 2015, pulling in 1.44 billion RMB. The duo’s latest, Hello Mr. Billionaire, came out in theaters last weekend, and the box office has already reached 1.29 billion RMB at this writing.

Another filmmaking duo — Song Yang and Zhang Chiyu — reached #2 on the list on the strength of another Mahua play adaption, Never Say Die, which made 2.21 billion RMB in total upon its release last year.

As for romantic films, the #3 spot on the list went to Tian Yusheng, whose third film in The Ex-File series made 1.94 billion RMB at the beginning of this year. Su Lun surprised the market with How Long Will I Love U, a time-traveling urban love story she wrote herself, which ended up with 899 million RMB at the box office in June.

ARTHOUSE FILMS

Bi Gan (#9), a 29-year-old filmmaker of the Hmong ethnicity, won Best New Director at the Golden Horse Awards in Taiwan, Golden Montgolfiere at the Festival des 3 Continents, and Best Emerging Director at Locarno Festival with his 2016 debut, Kaili Blues (pictured up top). Bi’s latest film, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, premiered at this year’s Cannes festival, and will hit Chinese theaters later. As a poet and photographer who didn’t attend any film academy, Bi has his own way of observing and expressing thoughts about the world.

Related:

Zhang Dalei (#25) and Zhou Ziyang (#27) were both nominated for Best New Director and Best Original Screenplay at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards. Zhang’s The Summer is Gone (2017) and Zhou’s Old Beast (2017) were also nominated for several awards at the FIRST International Film Festival (formerly known as Chinese College Students Film Festival), which was founded in 2006 and focuses on first features and early works by emerging filmmakers.

Starting from FIRST as well, Xin Yukun blurred the line between arthouse and commercial film with his The Coffin in the Mountain (2015) and Wrath Of Silence, which made 54.3 million RMB this year.

Cai Chengjie (Mirrors and Feathers, in theaters now) and Lhapal Gyal (Wangdrak’s Rain Boots) won Best Director awards at FIRST, and both filmmakers have drawn attention domestically and internationally.

FORMER WRITERS, ACTORS AND SINGERS

Han Han (#5) and Guo Jingming (#18) both first became famous as novelists before finding their way to the big screen.

Writer/racing driver Han demonstrated his filmmaking talent and sense of humor with The Continent (2014) and Duckweed (2017), starring Jia Zhangke, which made 1.67 billion RMB in total.

Guo’s Tiny Times and Legend of Ravaging Dynasties, meanwhile, made 2.17 billion RMB altogether, but the reviews of the films were less solid than their box office performance.

There are also a few famous actors becoming directors, such as Dong Chengpeng (A Hero or Not, 2015), Wen Zhang (When Larry Meets Mary, 2016), Wang Baoqiang (Buddies in India, 2017) and Xiao Yang of viral video duo Chopstick Brothers (Old Boys: The Way of The Dragon, 2014).

THE NEXT GENERATION?

Each of the directors on this list found their own unique path to success — a path that was harder for some than for others. “I think everyone’s first feature film is difficult,” Mirrors and Feathers director Cai Chengjie said in a recent interview (link in Chinese). Unlike actors or writers who might have a pre-existing fanbase to guarantee a box office triumph, young directors have to find a way to start from scratch and obtain the necessary investment to allow their works to be seen. Fortunately, several ongoing projects are aiming to help the new wave of Chinese filmmakers realize their dreams.

Ning Hao’s Dirty Monkeys Studio launched its 72 Transformations Film Plan to support young directors shortly after its founding in 2016. Ning himself is a veteran comedy director, whose 2006 film Crazy Stone was sponsored by Focus First Cuts, a project spearheaded by Hong Kong actor Andy Lau. Now Ning is giving back with his studio’s plan, with the stated mission of supervising the work of ten young directors.

After the success of Wen Muye (Dying To Survive) and Lu Yang, we can look forward to the next crop of films from this project to come out soon, including Liu Xiaoshi’s sci-fi film Beyond Time, Zeng Zeng’s art romance A Journey to Cross Cloud and Water, and Niu Han’s A Sweet Life. Ning’s own Crazy Alien, co-created by Three Body Problem author and Chinese sci-fi legend Liu Cixin, will be released in 2019.

Related:

Other institutions are also getting in on the process of nurturing future filmmaking talent. SARFT — the central government branch that oversees films made and distributed in China — launched its CFDG Young Director Support Program in 2015, inviting Feng Xiaogang, Jia Zhangke, Tian Zhuangzhuang, Zhang Yimou and more to choose and mentor five young directors, with support of millions of RMB.

China’s big-three tech companies — Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent, or BAT — are everywhere. In FIRST’s annual financing program, we can see Tencent Pictures’ NEXT IDEA Plan, as well as Alibaba Pictures’ Plan A Screenplay Developing Fund, which sponsored Zhou Ziyang’s Old Beast. Baidu-owned iQIYI also launched an initiative called Plan 17 last year, which sponsored Zhang Dalei’s The Summer is Gone.

China’s two biggest film festivals, the Shanghai International Film & TV Festival and Beijing International Film Festival, have set up initiatives called PROJECT Lab and Project Pitches, respectively, looking to attract and nurture young talent.

On July 30, the 12th FIRST International Film Festival wrapped up in the northwestern city of Xining, closing its festivities with a screening of this year’s winner for Best Narrative Picture, Qiu Cheng’s Suburban Birds. The festival opened earlier in the month with An Elephant Sitting Still by director Hu Bo, who was selected for last year’s FIRST Training Camp and won financing from Wang Xiaoshuai’s production company. (Tragically, Hu committed suicide last October after completing his first feature.)

Related:

Other films included in this year’s FIRST Festival were Yang Mingming’s Girls Always Happy and Hao Wu’s People’s Republic of Desire, both of which RADII has reported on earlier this year.

While there may not be clear lines defining a “seventh generation,” it’s clear that there are more opportunities than ever for young filmmakers in China today. The fact that more young directors have more ways to make the films they want to make will undoubtedly make a profound difference on Chinese cinema in the years to come.

—

Cover image: Still from Kaili Blues by Bi Gan (via Grasshopper Film)

You might also like:

https://radiichina.com/ticketing-platform-tao-piao-piao-invests-300-million-rmb-in-arthouse-cinema/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]