Over the recent Dragon Boat Festival holiday, as others were nibbling on zongzi (粽子), a childhood friend and I decided to head to Nanjing, a 1,200-year-old city famous for — among other things — being dotted with small-time culinary gems. We came, we saw, we ate. But beyond the food, we got to experience another interesting phenomenon: the impact of KOLs on young consumers in China.

“Old Man’s Hermès Sour Bean Fried Rice” may sound like a slightly odd, luxury brand-referencing restaurant, but it’s ranked as Nanjing’s number three small eatery out of thousands on Dazhong Dianping — a restaurant review, table booking and takeout app, often referred to as “the Chinese Yelp.” An otherwise nondescript outlet, the humble spot shot up the app’s charts after receiving praise from a KOL, a Key Opinion Leader whose social media presence was enough to completely redefine the outlet’s brand image.

This phenomenon is now being witnessed up and down the country, and isn’t only turning hole-in-the-wall eateries into centers of culinary pilgrimage overnight, it’s also caused big name brands to completely rethink their engagement strategies.

The Making of a “KOL Store”

The KOL store (网红店 wanghong dian, literally “internet red store”) is a concept made popular in China over the past few years, alongside the rise of KOLs themselves on social media channels such as Weibo, Kuaishou, Douyin (TikTok), and WeChat.

The KOL store poster child is a brand called “Heytea.” To get a cup of their famous cheese tea, you’ll likely need to stand in line for anywhere between one to ten hours, depending on the location of the shop. Their customers are predominantly students and young professionals, digital natives who constitute the base audience for online influencers. In 2012, Heytea started out as a small store in Shenzhen. Now, the chain has expanded to operate 90 locations across 13 cities in China, and just closed their latest fundraising round with 400 million RMB.

Some common motifs in KOL stores are long lines out the door and around the street, reflective of the store’s popularity, and usually a specialty focus on one signature product.

Both were on display when we visited Old Man’s Hermès Sour Bean Fried Rice. After waiting 30-plus minutes in line outside the store, we were ushered over to a tiny table for two, squeezed into a corner of the one-room restaurant. We ordered the most popular dish on the menu, Fried Rice with Intestines.

The fried rice seemed rather unremarkable to me. But it was clear that the young clientele around the restaurant was enthusiastic about it. Most were young students, regular faces in the lunch and dinner crowds.

Sophia Han, a 31-year-old working in Shanghai’s food and drink scene, is a regular visitor of KOL stores.

“Going to the influencer stores is like being part of a treasure hunt. You’re following in the footsteps of some KOL, but collecting your own unique experiences.”

Talking with the owner of Hermès Sour Bean Fried Rice, I learn that the restaurant started out as a street stall, hawking fried rice on the same corner of the road every day around ten years ago. A few years back, a popular KOL happened to walk by, stopped to try the food, and decided it was worth sharing with her fans.

The stand’s popularity exploded. People would pull up in Ferraris and Maseratis to get out and sit on the tiny plastic stalls in the street while they ate. On one afternoon in August 2015, they had over 300 people trying to get their hands on some fried rice. The police even turned up to find out why there was such a throng.

Since then, the store has grown from a street-stand into a two-story restaurant, and visitors come from all around the country to taste the infamous “Hermès Fried Rice.” The owner told us that they now sell over 3,000 orders per day.

What’s driving the popularity of KOLs?

Elijah Whaley is CMO of Parklu, an agency in China that manages and monetizes online influencers. He cites a direct connection to niche communities as the key value of influencer marketing — something he’s witnessed at close quarters. Before becoming CMO of Parklu, Elijah and his girlfriend Maggie managed to successfully launch her career as a beauty influencer. In less than two years, she’s become one of the top twenty beauty KOLs on Weibo.

“We started in August 2015 as a small project. By March the following year, we had around 60,000 followers, and a luxury bag brand approached us to sell their branded bags on consignment. We took on the project with a testing mindset, but five days after launching the campaign we’d already sold over 25,000 USD in bags. It was then that I realized something very special was happening in China.”

Maggie’s Weibo account, MelilimFu, is currently among the top twenty beauty influencer accounts on the platform

Online influencers in China aren’t just representative of aspirational lifestyles, but voices that speak to a highly niche set of interests. No matter how specific your interest, there’s a forum and a community of peers to be found.

For China’s post-’90s generation, distrust or skepticism of traditional information channels is often a given. Online influencers represent an alternative source of credible information from peers.

While it’s difficult to accurately estimate the precise number of influencers in China, a Makershow study shows that there are over 10,000 individuals on Weibo who have followings of over one million, and the total value of the influencer market is estimated at over 800 million USD.

I take photos of my Fried Rice with Intestines, trying to make it look appealing and Weibo-worthy. Many customers before me have gone through the same rituals on their own pseudo-influencer journeys. The drive to share our lives in the digital age is growing more complex every day, and the influencer wave is on course to change how young people in China interact with the world around them.

You might also like:

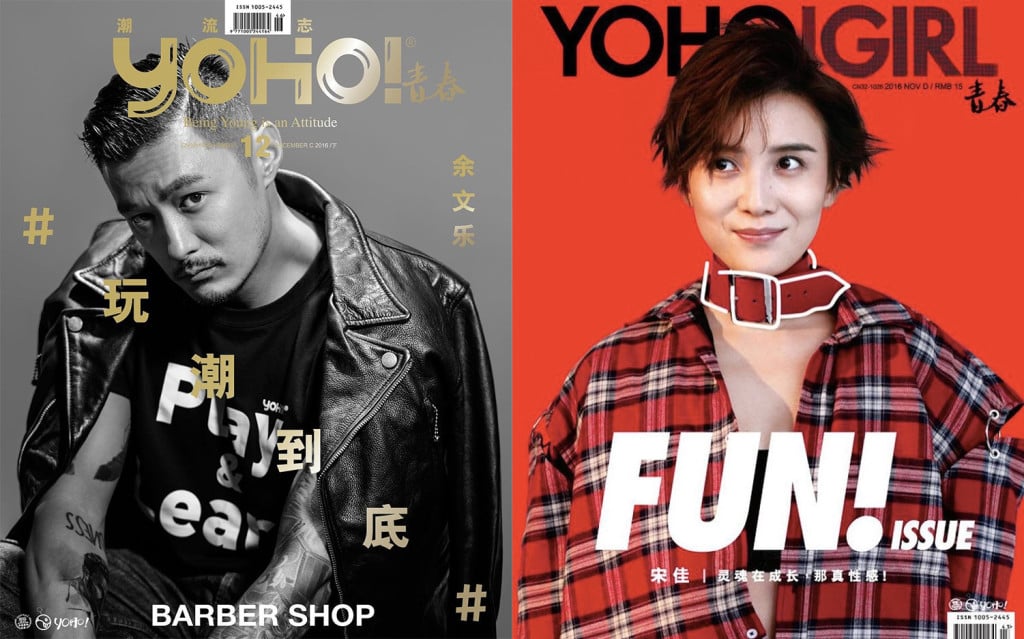

How a Magazine-Turned-App is Redefining China’s Fashion LandscapeArticle Oct 13, 2017

How a Magazine-Turned-App is Redefining China’s Fashion LandscapeArticle Oct 13, 2017

Google Invests in JD.com as the E-Commerce Site Eyes Further Global ExpansionArticle Jun 18, 2018

Google Invests in JD.com as the E-Commerce Site Eyes Further Global ExpansionArticle Jun 18, 2018

Don’t Bring Lawyers, Guns and Money to ChinaArticle Dec 04, 2017

Don’t Bring Lawyers, Guns and Money to ChinaArticle Dec 04, 2017