Editor’s note: This article was originally published by TechNode. It has been re-posted here with permission.

On a scorching night in August, thousands of Chinese youngsters filled a grand stadium in Nanjing to celebrate the four-year anniversary of the Chinese boyband TFBoys. Those who couldn’t attend — 118 million of them — spent a no less memorable night by watching the shows aired over the internet. Screams became a waterfall of real-time comments, called danmu, rolling across the live video. Regrets over not making it in person materialized into 340 million units of virtual gifts sent through the live streams, all of which were run by Tencent that night: QQ Zone, QQ Video, QQ Music, WeSing, Kuwo, KuGou, and KuGou Live.

None of these products, except KuGou Live, were designed specifically to live stream. That’s the point. A user of the social network QQ Zone, for example, wouldn’t have to switch over to KuGou Live to watch her idol TFBoys. Tencent — the Chinese tech giant that has revolutionized how people communicate, pay for, and play video games — is now ready to redefine the ways music is consumed.

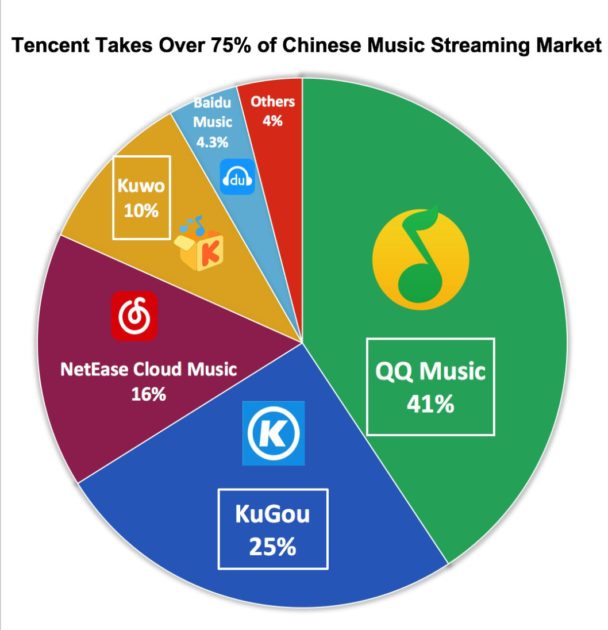

To start with, Tencent has been able to dominate almost the entire market. Last July, its flagship music streamer QQ Music merged with competitor China Music Corporation (CMC) to form Tencent Music and Entertainment Group (TME). Together, Kuwo and KuGou — formerly owned by CMC — and QQ Music, control a whopping 75% market share, according to a report by the Data Center of China internet (DCCI).

Top music streaming apps in China 2016-2017 (Data source: DCCI; graph by TechNode)

That dominance alone, however, doesn’t equal a lucrative business. For decades, Chinese people have gotten used to getting music for free in a piracy-unhampered country. “Our number of monthly active users accessing music is actually over 600 million, which means, at 15 million [paying subscribers], our conversion to subscription is still less than 3%,” says Vice President of TME Andy Ng in an interview with International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). He adds that in more mature markets, the percentage is around 20-30%.

But Ng is optimistic: “We see a huge opportunity and potential for growth.” The numbers are no doubt promising. In 2016, recorded music revenue in China grew 20.3 percent driven by a 30.6 percent growth in streaming alone, according to IFPI. And the music giant is already finding ways to lure Chinese people into paying something that used to be so easily free.

Unmatched copyright control

While licensing fees can easily eat up the bulk of revenues, Tencent knows that in the long run, the investment will pay off. In May, TME signed with Universal Music Group (UMG), the last one of the “Big Three” record labels to strike an exclusive licensing deal with the Chinese music giant. With the added roster of major Chinese labels through the CMC merger, Tencent’s streaming rights in China is unrivaled.

The music giant also sub-licenses this content to competitors. One of them is NetEase Cloud Music, the music subsidiary of Nasdaq-listed NetEase Inc. Over the past two years, QQ Music and NetEase Cloud Music have been aggressively suing each other over copyright infringement, hoping to snag users once certain music became exclusive on their own platform.

The copyright bloodbath is happening against a backdrop of China’s tightened regulation over online music. In July 2015, the government finally stepped up to order all internet music providers to delete their pirated content. Samuel Chou, CEO of Sony Music Entertainment China and Taiwan, went as far as calling 2016 “the first year of a new era for music in China”.

Beyond music streaming

Adding more legal gunpowder, however, is not enough. “Music was considered a free commodity in China for so long that it will take time to change people’s perception,” reckons Simon Robson, President of Warner Music Asia. “We’re talking about a situation where about 90% of the market was piracy.”

To help smooth the transition, Tencent charges little. QQ Music has a three-tier monthly fee at RMB 8 and 12, and 15 ($1.22/$1.83/$2.18). In comparison, Spotify Premium is priced at $9.99 a month. But this is nothing new to Chinese users, who have long been beneficiaries of the constant price wars between internet companies heavily subsidized by investors. The bike-rental battle is a sobering example. Kuwo, KuGou, and NetEase Cloud Music all offer similar price points as QQ Music.

Just as Tencent’s WeChat goes beyond a messaging app to permeate every aspect of the Chinese service economy, TME is building an ecosystem of value-added services around music streaming to make music pay. Basic tactics include perks for premium users like concert tickets, professional sound quality, and game credits—a luxury from having a parent company with a global dominance in online gaming.

Tencent’s ecosystem of apps that were used to stream TFBoys’ concert (Poster image: TFBoys; graph by TechNode)

QQ Music also tested out what it’s called the “digital album”. When the platform released a high-profile album, it will take the album out of the streaming pool and offer it for a one-off fee. After two to three months, QQ Music will then migrate the album back to its streaming service.

The model has seen some initial success. When the original soundtrack of Fast and Furious 8 came out on QQ Music, it sold over one million digital copies within a week. “[Chinese young people] are happy to spend a few dollars supporting the artists they truly admire,” said Ng to IFPI. According to the DCCI, over 90 percent of QQ Music’s users were born after 1990.

Lastly, Tencent has looked beyond the audio and tapped into arguably the hottest buzzword swirling around the Chinese internet circle since 2016: video live streaming. A recent report by iResearch puts the market at an estimated RMB 20.8 billion (around US$ 3 billion). Audiences fixated on their screens toss virtual gifts over the virtual stage to their idols—be they established star under the spotlight or farmers toiling in the potato field from a small town. The online fervor for TFBoys proves that there is still room for Tencent in the crowded space.

TFBoys concert live streamed via QQ Music (Screenshot taken from the QQ Music app)

Tencent certainly hasn’t overlooked Chinese people’s obsession with karaoke. WeSing, an app that lets users sing karaoke on the phone and share the recorded work with friends and strangers, has surged to become the biggest player in the vertical totaling 460 million users (in Chinese). When the live streaming wave hit, WeSing naturally bolted the function onto the platform, and virtual gifting has, in 2016, gained popularity on the app as highlighted in Tencent’s annual report.

Turning a profit

With an array of business models surrounding music streaming, TME is already giving revenue boost to its parent company. In 2016, Tencent’s social networks revenues increased by 54 percent to around $4 billion (though still dwarfed by the its $10 billion gaming revenues). That increase mainly reflects growth in digital content services, which include Tencent’s music business and virtual item sales. According to someone familiar with the matter, a significant amount of TME’s live streaming revenues came from KuGou Live, in which Tencent has a controlling stake via the CMC merger.

QQ Music is also, amazingly, profitable. Over in the west, Spotify has yet to reach profitability despite having 20 million paying customers. Like Spotify, the biggest source of revenues for the Chinese music app are monthly subscriptions followed by advertising (in Chinese). As TME is on course for IPO at a $10 billion valuation, the world will be listen closely to how it makes its numbers sing.

Cover photo: Yahoo Finance