For years, China’s hip hop community was thin and disparate. Early acts like Six City from Xinjiang and Yin Ts’ang from Beijing propped up the skeleton of a scene, but without muscles or organs, hip hop as a cultural force never managed to penetrate the mainstream.

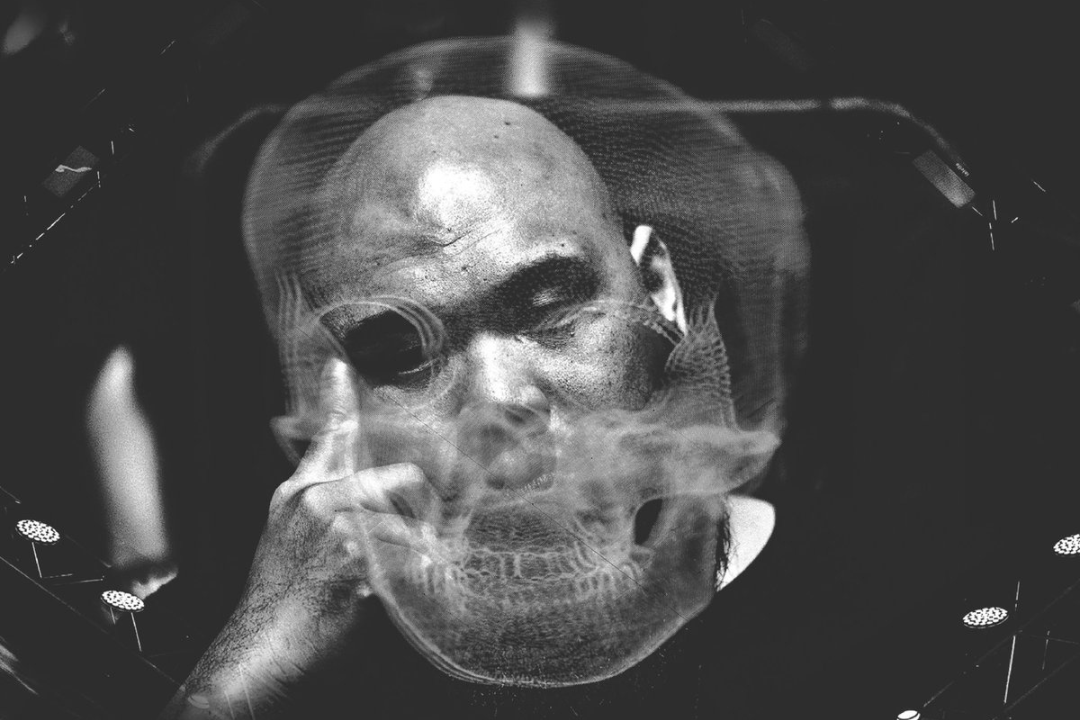

But now in the era of smash hit reality TV show Rap of China, hip hop is battling for a position at the head of China’s pop cultural identity. The frontline is Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province and home to the new generation of Chinese rap — in no small part due to the work of Kafe Hu.

Kafe is a rap pioneer, whose expansive catalogue has seen him go bar-for-bar with other rap greats, while also managing to diverge into untread territory. In the infancy of Sichuan’s scene, inspired by his father’s bootleg VCDs of DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, and by Korean hip hop TV segments, he took up the popping dance style. Shortly after that he started to record his own raps on a cheap USB mic. More recently, he’s released an entire album over a live jazz band, collaborated with producers and artists across every genre, and had a son.

We sat down with Kafe at Eating Music to talk about Sichuan’s hip hop origins, artistic purity in a commercial industry, and the growth that comes with starting a family.

Early Rap in Chengdu

RADII: So first off, when did you start listening to hip hop, and when did you start rapping?

Kafe Hu: I was 14 when I first heard hip hop. And since we’re on this topic, I have to mention my hometown. Everybody thinks I’m from Chengdu, but I’m actually from a smaller city called Jiangyou. The only culture there was food and tourism, so everything around me was just buses and restaurants — there was basically zero hip hop there.

One day my friends and I saw a Korean show with people doing hip hop dance — but we didn’t know that term back then. They were dancing to some rhythmic music, which I later learned was Eminem’s Slim Shady LP. It left a lasting impression on me, and that was the first time I heard rap music. Well, almost. When I was young, my dad bought some illegal VCDs… some Fresh Prince, De La Soul… so really, by the time I was 10, I had already listened to a lot of old school rap. But the first time when I actually knew it was hip hop, it was Eminem.

The reason I started rapping was because I realized my body wasn’t good for hip hop dance. It looked awful (laughs), so I wanted to do something else that was cool. That was around the time we got a computer in my house, and I started searching online for rap albums. 50 Cent, T.I., Jay-Z….

Eventually I found a Chinese rap forum online. A lot of people rapping on there sounded terrible, but the feeling was there. Other users showed me how to download a cracked version of some recording software, so I could record raps over instrumentals. You didn’t even need a VPN back then, so I downloaded a ton of beats. That was the start of me rapping.

The first mic I used was a 25 dollar computer microphone. Our computer didn’t have a headphone jack, so I turned the volume way down and put my ear next to the speakers to record. The first songs I recorded were probably trash, and the lyrics were meaningless. At least I didn’t try to say I had a gun.

The first songs I recorded were probably trash, and the lyrics were meaningless. At least I didn’t try to say I had a gun.

Word, humble beginnings. What kind of hip hop dance did you do back then?

I did popping, but it was like… super ugly, man. You could never imagine how fucking terrible my popping was.

Any videos still online?

You want a video? I’ll do it right now.

Related:

The History of Rap in China, Part 1: Early Roots and Iron Mics (1993-2009)No, it didn’t all start with The Rap of China — far from it. In Pt. 1 of a two-part series, Fan Shuhong traces the history of hip hop in China from the 1990s to 2010Article Feb 01, 2019

The History of Rap in China, Part 1: Early Roots and Iron Mics (1993-2009)No, it didn’t all start with The Rap of China — far from it. In Pt. 1 of a two-part series, Fan Shuhong traces the history of hip hop in China from the 1990s to 2010Article Feb 01, 2019

No worries, I’m playing. What was the scene like in Sichuan and in Chengdu back then?

Well at the start it wasn’t rap that was popular, but breakdancing. It was really big in China back then, so when I got to Chengdu there were already a lot of hip hop fans, wearing oversized clothes, dancing. There was one group that was always doing street performances for 100RMB a pop. Meanwhile, rap was really overlooked. People brushed it off — it seemed like an infant learning how to walk. When I see my son walking, he can’t walk well, and sometimes he falls. Rap that I saw in Chengdu twelve years ago was like that.

When I first went to Chengdu, there were only a few people who were rapping. Later there were ten, then twenty, now Chengdu probably has over a thousand rappers. So it grew like that. The hip hop dance era is over, the rock era is also over, but rap is still pushing on. More and more people started coming to our shows — I remember one performance with Chengdu Rap House, the first time the audience was over 1,000… that was when we realized that rap could be successful in Chengdu.

Related:

WATCH: Nardwuar vs. Higher BrothersArticle Mar 06, 2018

WATCH: Nardwuar vs. Higher BrothersArticle Mar 06, 2018

Now Chengdu’s hip hop influence is huge, like Higher Brothers who have signed with American labels. Masiwei is very smart, and DZ is a great singer. They have the skills and planning to get to where they are, so I congratulate them. That kind of thing is why everyone thinks Chengdu is the pioneer of hip hop in China. But I don’t like to talk big like that — I think hip hop is good everywhere.

The most important thing isn’t just the rapping, but also that the audience is willing to listen to the music, and not just care who’s holding the mic. If they just care about the artist, it’s the same as how we all liked [pop star] Andy Lau when we were young.

A culture’s progress isn’t from one person, but from a group of people. It’s probably not the answer you were looking for, but I think it’s my responsibility to explain that hip hop is the same throughout the whole country. The internet reaches everywhere, and hip hop has reached everywhere in China. It’s better to say that hip hop has developed in all of China, rather than just in Chengdu.

So is an educated audience more important for the development of the genre than the rappers themselves?

Always. The audience is always more important than the artists. Everyone wants to be a rapper — if you’re hardworking you can be one. But for the audience, there’s no handbook that teaches you how to be aware, or “here are the things you’re supposed to understand.”

You mentioned before about breaking and hip hop dance being the first aspects of the culture to really take off here, starting off small in parks or community centers. But now in Shanghai, everywhere you look there are dance studios, instructors, classes at universities. So that’s a big change from a small grassroots thing to a big commercial thing. Do you think rap and the music side will go through a similar transformation?

They’re doing it right now! Rap here is going through that same thing that breaking did. At the beginning, everyone just did it in the streets. When they had money, they made a studio, opened a company, taught students. In the beginning, rappers didn’t have money either, so we’d just freestyle on the street.

Later when we had money, we could buy microphones, open studios, and form labels. Nowadays, there’s no rap in the streets. Can you see rapping out in the streets of China? When a culture develops, and money starts coming in… well, just look around us. Even Eating Music is already set up in a fancy space like this!

The Meaning of Art

You’re known by a lot of your fans for your meaningful, true-to-life lyrics. What’s your writing process like? And is it important to you that you don’t write about overly commercial subjects like cars and money?

I don’t really choose. I don’t think about what to say or write, it’s just an extension of my personality. I don’t have cars, jewelry, or women hanging at my side — if there are women with me, they stay there for an hour, then they leave with other guys. So my life isn’t like that. I can only write about what happens in my life. I can’t lie and say that I was driving a really expensive car, with a girl with basketball-sized boobs.

I’ve never thought about what to write. It’s not like cooking, where I have to choose what recipe I’m going to make. Sometimes inspiration is like taking a dump. You sit on the toilet for half an hour and nothing comes out, but when you’re walking around unprepared, you might nearly shit yourself.

People say my lyrics are kind of poetic, or hard to understand. I think that’s a big misunderstanding. When you’re good at something, you won’t do it in a normal way — you’ll do it in a meaningful way. If you don’t understand the lyrics, don’t try to understand them.

If you go to a museum and look at a painting and say, “what is this trying to represent?”, then you won’t get the meaning, no matter how hard you try. Why not look at rap like we do paintings? To me, rap is a form of art. And if that’s the case, sometimes you don’t need to understand the lyrics.

If you don’t understand the lyrics, don’t try to understand them. If you go to a museum and look at a painting and say, “what is this trying to represent?”, then you won’t get the meaning, no matter how hard you try. Why not look at rap like we do paintings?

Well said. How do you feel about artists who do rap about more commercial things? Especially if it’s not true. If an artist doesn’t have a nice car and women all over him, but he raps having a nice car and women all over him, is that acceptable, or artistically dishonest?

I’d say they’re the same as me. We all have to “keep it real”… but keep what real? It’s whatever you want — that’s what’s real. Sometimes I rap about the dreams I want to achieve, and my dream isn’t about cars, jewelry, and women. But maybe for others it is.

Before, there was the American dream. Now there’s the Chinese dream. It’s the same idea — these rappers are all speaking their Chinese dream. You might say they’re imitating the American dream, or the African-American dream. But at our core, we’re all the same. I think there’s no difference between these rappers and myself.

On his Discography

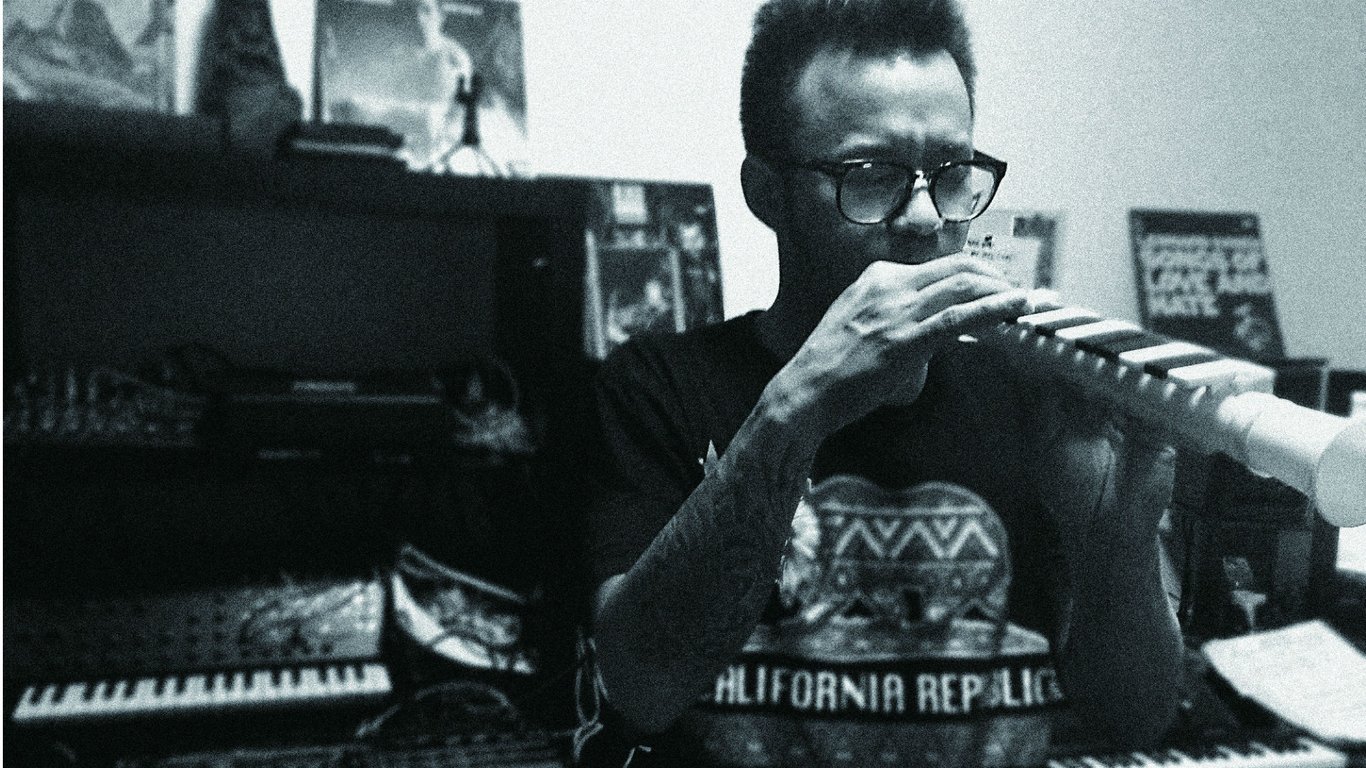

Your album Kafreeman — that was all live bands and instruments, no samples or electronic beats. What was that experience like, and what made you want to take on a project with all live musicians?

I’d wanted to do an album like that for ten years, but it was impossible. And back then, there just weren’t many good jazz musicians in Chengdu. You could say that China’s jazz music developed under difficult conditions. I’m not very well-versed, but I’ve never heard much good Chinese jazz, myself.

So ten years later, I had the capability. I signed to Modern Sky, and I had the money to pull it off. So I grabbed some musicians I’d worked with in the past, and formed a band. We spent seven straight days in the studio to make that album.

I thought, man, my earliest dream fulfilled after ten years. There was an American rapper I knew who recently passed away in Los Angeles; when he was living in Chengdu he told me that if you do something for ten years, it’ll become your career. And it really did take ten years to make Kafreeman.

The album wasn’t a smash hit in China, even though it won awards from critics. They were intrigued because they’d never seen this type of album before, rap with high-level jazz artists. The bass player, Gustam, was their leader. They were all from Mauritius — Gustam’s grandfather was a guitarist, his mother sang and played keyboard, and his father played drums and guitar. When they were younger, 19 or 20 years-old, their town still didn’t have internet, so their hobby was just playing music.

At that time my son was less than a month old. Sitting there in the studio, I really missed him. Whenever we left the recording booth, we’d be back within a couple hours.

Seven straight days in the studio… what was that like?

It was like shit, man.

What about your recent album with Kai-Luen (Soulspeak)?

That one was really different — when I make an album myself, I don’t think about it too much. Soulspeak on the other hand, he takes everything into consideration. He’s truly a self-made man.

Related:

A Decade of Sound from Jeff Kai-Luen Liang, aka Soulspeak (Exclusive Mix)The formerly Beijing-based beatsmith also known as Soulspeak digs in to his archives for some choice cuts from his studio ca. 2010-2019Article Apr 10, 2019

A Decade of Sound from Jeff Kai-Luen Liang, aka Soulspeak (Exclusive Mix)The formerly Beijing-based beatsmith also known as Soulspeak digs in to his archives for some choice cuts from his studio ca. 2010-2019Article Apr 10, 2019

This album is 50% Soulspeak, 50% Kafe Hu. I’m just writing the lyrics and performing them, and even in the recording process, I accepted a lot of input from Soulspeak. It didn’t take us long to produce the music itself. He’d make the beat, I’d write the lyrics, and then we’d take it to the studio to record, just chilling and kicking it in Beijing together.

This album’s title is Fame Fake. People would ask me what it meant, and it’s hard to explain. It’s this phrase I made up, “you’re famous or you’re fake.”

If people really like hip hop, they should listen to good Chinese rap. A lot of people say rap is dumb — it’s not that rap is dumb, just that a lot of dumb people do rap. So this is what I’ve been saying all along.

If people really like hip hop, they should listen to good Chinese rap. A lot of people say rap is dumb — it’s not that rap is dumb, just that a lot of dumb people do rap.

Becoming a Father

You became a father not long ago. How old is your son, now?

He’s one and a half.

Congratulations. What’s changed since you had a kid?

I wanna puke, man. I feel a lot of love ever since I had my child. He’s very cute. I also became more loving, because you have to be loving towards your children. And he’s helped me become more aware of my appearance — even though I still don’t really look like a father, at least I don’t look like a fucking street punk.

That’s what I used to look like, so I’ve already changed tremendously. But there’s also pressure, because you feel like you need to earn a lot of money. One misconception is that people think I’m really rich now, but I’m not. My money is what I earned this year, and next year I’ll have to work again. Not like I can just take it easy and play video games. I really love video games, so if I didn’t do hip hop, I’d be a fucking super duper nerd. I’d be fat, with glasses, sitting at home with stinky feet and playing games.

And your son must give you some inspiration for your work, right?

Of course. My son gives me a lot of inspiration for my music. After he was born, my lyrics would constantly mention family, either that or money. I’d joke about how he’s waiting for me to buy his mother a pearl necklace.

After becoming a father, you have to earn more money. And when you think about money more, you become more materialistic. That’s what I’ve been going through.

The Future of Chinese Hip Hop

You’re kind of an OG in China’s hip hop scene right now. How did you achieve success before there was an industry?

It was really sudden, and really natural. Back then it was just like, people come to your performances, and if they like it, they’ll tell more people to come.

But another thing worth mentioning is that some fans stick around, while others decide they’re too old for this kind of music and leave. The younger fans are pulled towards younger rappers, so I’m basically becoming less and less famous. In the end, I will evaporate.

Right now, Chinese hip hop is taking off because of Rap of China. How do you feel about that? You’ve been doing this since way before it was popular, and now you’re seeing everybody else jump onboard. Are you excited about it, worried about it… how do you feel?

To be honest, it’s just a show, so I’m not happy or angry about it. With Rap of China, everyone’s caught the fever and suddenly thinks rap is cool. But it’s just for TV, just trying to be what the audience likes. If anything, I can be happy because I’m part of this industry and my ticket prices might go up. These shows are like the stock market — if your stock rises, your income rises.

I don’t feel happy or sad about it — what’s there to be sad about? I don’t have a loser mindset or low self-esteem. One person alone can’t change a culture, even if they are superhuman. With Rap of China, I try to keep a calm mindset about it. If you gain from it, you can be thankful. If you feel angry about it, try not to share those feelings with other people — whatever you say is going to be dumb.

Related:

“Rap of China” Gears Up for Season 3 Despite Waning InterestAs the global horizon for Chinese rap expands, future prospects for the show that blew it up might be starting to shrinkArticle Mar 27, 2019

“Rap of China” Gears Up for Season 3 Despite Waning InterestAs the global horizon for Chinese rap expands, future prospects for the show that blew it up might be starting to shrinkArticle Mar 27, 2019

Rounding up on the end here. During the peak of Rap of China’s influence, governing bodies decided that hip hop was a dangerous thing. In that kind of environment, do you face pressure as a rapper known partly for your lyrics about social issues?

Is there pressure? Well, I’ve never felt any. A lot of people have asked me this and I didn’t respond to them, but I’ll respond to you. The regulators are against what they think is truly dangerous, but those kinds of things aren’t present in my life, and they’re not the things I want to express. So there’s no impact on me at all, but it may influence other rappers.

The regulators are against what they think is truly dangerous, but those kinds of things aren’t present in my life, and they’re not the things I want to express.

What do you hope for Chinese hip hop in the years to come, and what worries you about the future of Chinese hip hop?

I hope Chinese hip hop can change, I hope I can be king. I’m most worried that I won’t be king of Chinese hip hop. (Laughs)

Truthfully, there’s nothing I’m worried about. Let’s just see how it goes.

—

Additional assistance from Ying Li, Katherine Wang and Elizabeth Wang