This is Part 1 of a two-part series on the history of rap in China. Find Part 2 here, and see more of RADII’s in-depth hip hop coverage here.

“Dakou” cassettes featuring Eminem and Taiwanese rapper MC Hotdog, and my classmates dancing at school, imitating Korean boy band H.O.T. — this was my “Hip Hop 101,” my first taste of rap as a middle schooler in Beijing at the turn of the millennium.

But if we want to take a deeper dive into the real history of rap in China — a history that goes far beyond the mainstream version exemplified by hit reality show The Rap of China — the origins of this culture date back to a decade earlier.

1990s: The Emergence of Rap in China

Even though rock and pop artists Cui Jian (Beijing), George Lam (Hong Kong), and Harlem Yu (Taipei) had injected some rap elements into their music even before 1990, the genre didn’t really garner widespread attention until the release of Someone (某某人) in 1993. The album’s cover literally had the words “China Rap” on it, along with a photo of Xie Dong, Yin Xiangjie, and Tu Tu, two of whom went on to help form the first generation of pop singers in Mainland China.

Around the same time, in 1992, Dai Bing and Tian Bao formed the first rap group in China, D.D.Rhythm.

Li Xiaolong, a former B-Boy from Fujian who is widely regarded as “the first Chinese rapper,” also got his start in the mid-’90s, and eventually went on to rap the theme song for hit TV series Loquacious Zhang Damin’s Happy Life. (This was in 2000, long before last year’s supposed “ban” prohibiting rappers from appearing on broadcast television.) Li, who has the same Chinese name as Bruce Lee, released his debut album Li Shao Long in 2000.

In 1994, national sports station CCTV5 began broadcasting NBA games for the first time. In addition to introducing professional basketball to China, the background music of the televised games and the players’ style gave young Chinese a new avenue through which to encounter hip hop. Two years later, Korean boy group H.O.T. was formed, and became another important gateway for Chinese fans to get a taste of hip hop music and street dance.

In 1999, another influential group, 黑棒 Hi-Bomb, was founded in Shanghai. The group remains famous to this day for their hit song “霞飞路87号 No.87 on Xiafei Road”.

That same year, a group of friends in Hong Kong going by the name LMF released their debut EP, the self-titled Lazy Mutha Fucka. The group featured MC Yan, who went on to produce Hong Kong superstar and sort-of rapper Edison Chen, and DJ Tommy, CEO of CMD Music and co-founder (with Chen) of hip hop fashion brand CLOT. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the group’s obscenity-filled songs stirred up a load of controversy, but also won them a dedicated fan base.

LMF recently returned to the live arena ahead of their 20th anniversary, giving of a handful of “Still Lazy” reunion shows in 2018. The group plans to release new music, and has seemingly found a new audience for their authority-challenging lyrics in present-day Hong Kong. (LMF has only been permitted to play on the Mainland once in their career.)

Across the strait in Taiwan, hip hop had hit earlier via L.A.Boyz, a group of three Chinese-Americans (Jeffery Huang, Stanley Huang and Steven Lim) that was active from 1992 to 1997.

In 1998, a 20-year-old rapper by the name of Yao Zhongren started uploading his rap demos onto MU, Taiwan’s biggest online discussion forum for hip hop at the time. The website had been created by Lin Haoli and his friends, who would later found their own rap crew, TriPoets (参劈), in 2002. But the fame of both TriPoets and L.A.Boyz would ultimately be eclipsed by Yao, or as he’s better known today: MC Hotdog.

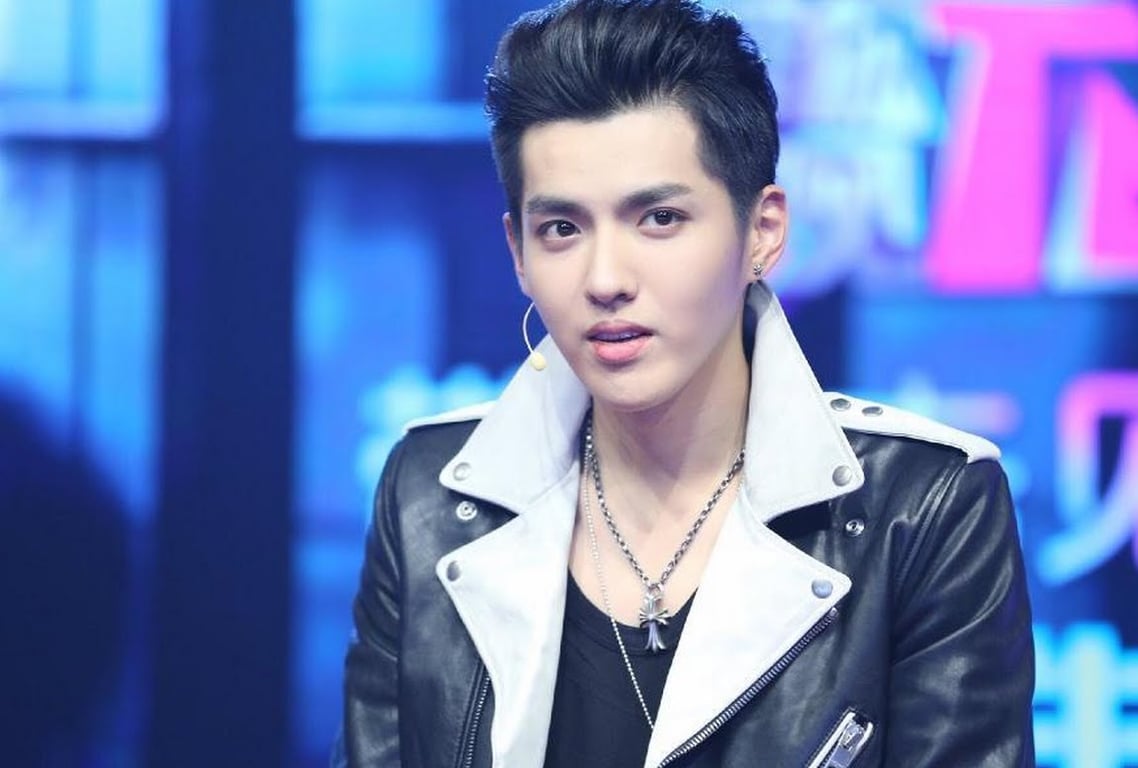

Although these days MC Hotdog and his longtime collaborator Zhang Zhenyue are often forced to play second fiddle to Kris Wu as judges on The Rap of China, there’s no doubting Hotdog’s impact on Mandarin-language hip hop. He became, and remains, a major star, and helped propel rap into the mainstream in both Taiwan and Mainland China.

2000-2009

When it comes to Chinese hip hop in the new millennium, we have to start with Yin Ts’ang (隐藏 ). Founded in 2000 by native Beijinger MC Webber (王波), Canadian-born Chinese hip hop head Sbazzo (马克), and American MCs He Zhong (贺忠) and Jeremy XIV (老郑), the group would only last a few years together, but their influence would be widespread and long-lasting.

Yin: ’90s Throwback with Yin Ts’ang, China’s Original Rap GroupArticle Oct 28, 2017

Yin: ’90s Throwback with Yin Ts’ang, China’s Original Rap GroupArticle Oct 28, 2017

Since 1998, Webber had been organizing a regular party in Beijing featuring live rapping, skateboarding, street dancing, and graffiti called Section 6. Early Beijing nightlife venue Club Orange became the home base for Section 6, and it was here that Webber would meet the rest of the Yin Ts’ang crew. In 2003, the group released their debut album, which was called Serve The People after an old Maoist slogan (为人民服务).

A year before the release of Yin Ts’ang’s album, Bamboo Crew (竹游人) was founded in Shanghai, featuring Zeero, the city’s first female rapper, and BlaKK Bubble, who rapped in the Shanghai dialect. Sbazzo from Yin Ts’ang and Young Cee from Bamboo Crew were the first two Chinese rappers to rhyme the last two characters of each sentence. The two groups’ dominance of Chinese hip hop at the time led to what was dubbed the age of “Yin Ts’ang in the North, Bamboo in the South.”

Yet this era was a brief one. In 2005, MC Webber left Yin Ts’ang to pursue other projects, while Sbazzo established another rap group, Bad Blood, and focused his energies on building a new hip hop-focused website with Jeremy XIV and Young Kin. The site, yinent.com (隐藏网), was a forerunner to hiphop.cn, which would become the biggest Chinese rap website of the time before being closed in 2009 following the global economic crisis.

Over in Taiwan Shawn Sung (宋岳庭)’s “Life’s A Struggle” was posthumously released in 2003, after the young talent moved to the US at the age of 14, went to prison, and died of cancer in 2002. “Life’s A Struggle” became a classic Chinese rap song that has inspired generations of music lovers, telling a true story from the bottom of society.

As the country’s most promising hip hop groups experienced short life-spans, an Asian-American rapper with an impeccable flow was showing some incredible staying power on popular American hip hop show 106 & Park. In 2002, Ouyang Jing (欧阳靖) — better known as MC Jin — was proclaimed Freestyle Friday champion seven weeks in a row, and became widely acknowledged as the first Asian-American rapper.

Although Jin has only found mainstream recognition in China in recent years, the reactions of participants on last year’s Rap of China series when he was revealed as a masked contestant spoke volumes about the respect he still enjoys in the community.

Who is the Mysterious HipHopMan? We Tracked Him DownArticle Jul 21, 2017

Who is the Mysterious HipHopMan? We Tracked Him DownArticle Jul 21, 2017

Back in China, another American was organizing the country’s first nationwide rap battle. Detroit-born Dana “Showtyme” Burton organized Iron Mic in Shanghai in 2002, crowning MC Webber as champion (a title he’d go on to take three consecutive times). Before he set up Iron Mic, Burton said: “Hip hop will be popular in China, because there are so many incredibly talented kids in such a big country.”

In subsequent years, Iron Mic helped a whole host of rappers gain fame in the underground scene, such as Taiwanese rapper MC DE-VI (茶米), who became the first new champion after Webber in 2005, and Wuhan-based rapper Big Dog, who was champion from 2007 through 2009. Years later, Big Dog would inadvertently become part of a Kris Wu-propelled meme after being asked a curious question by the K-pop star turned rapper — “Do you have freestyle?” — during auditions for the first season of The Rap of China.

It’s All “Freestyle” – How Meaningless English Buzzwords Define China’s Pop Culture TrendsArticle Aug 01, 2017

It’s All “Freestyle” – How Meaningless English Buzzwords Define China’s Pop Culture TrendsArticle Aug 01, 2017

Another key name at Iron Mic contests during this era was Bad Blood member and Beijing OG Lil Ray (aka Nasty Ray), who won 13 championships at different freestyle battles in this period, including being named the co-champion of 2009’s Iron Mic with Big Dog. Also a renowned DJ, Lil Ray would return to prominence in 2012 courtesy of his Natural Flavor hip hop party.

From 2001 to 2007, rap crews proliferated across China, including but not limited to: Kung Fu (功夫, est. 2001) from Tianjin, C.H.A.O.S (乱战门, est. 2003) from Xi’an, MaChi (est. 2003), No Fear (est. 2003) from Wuhan, D-Evil (est. 2003) from Nanjing, Bang Crew (喷嘭乐团, est. 2003) from Shanghai, Dragon King (龙井, est. 2007) from Beijing, Uranu$ (天王星, est. 2005), Prosa (讲者, est. 2005) and CHEE (精气神, est. 2006) from Guangzhou, Keep Real (est. 2003, later developed into hip hop label GO$H in 2012) from Chongqing, C-BLOCK (est. 2007) from Changsha-based label Sup Music, and Big Zoo (est. 2005) from Chengdu founded by Shaq G and Mow. Mow would also co-found Chengdu crew CDC (成都说唱会馆) five years later, along with Fat Shady, Ansr J, Lil Shin, Sleepy Cat, and others.

Back in 2006-2009, I was lucky enough to see a number of Big Zoo’s live shows in Chengdu (which also served as advanced Sichuan dialect listening practice for me). Back then, old-school, oversized jerseys were still in style. Chinese youths crowded into Chengdu’s Little Bar (小酒馆), an underground live music venue that’s now one of the most famous bars in the city. They nodded and waved their hands along with the rappers’ flows and the beats. Shaq G, one of my favorites, would sometimes come to the show straight from his white collar day job.

Around the same time, jazz rap emerged as a fresh new sub-genre in China, and Little Bar sometimes featured appearances from K-Bo (崔菲菲), the most active female Chinese R&B singer/rapper at the time. (K-Bo was tragically murdered in 2010.) There also were quite a lot of underground rap battles held in the city, attracting Sichuanese-speaking rappers from Chengdu and nearby Chongqing.

Related:

B-Side China Podcast: Chengdu Underground with Kristen NgArticle Oct 13, 2017

B-Side China Podcast: Chengdu Underground with Kristen NgArticle Oct 13, 2017

With American-born Chinese singer Jeffrey Kung (孔令奇) and Wes Chen promoting the culture to audiences in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou through their FM radio show The Park (嘻哈公园) from 2005 on, and Come Lee (李海钦), a former street dancer, launching the country’s first hip hop awards via his Hip Hop Fusion cultural promotion platform, Chinese hip hop was developing rapidly.

As the first decade of the 21st century came to an end, another seminal Chinese rap release emerged. In 2008, In3 (阴三儿, est. 2006) dropped their debut album Unknown Artist (未知艺术家 ) with a show at MAO Livehouse in Beijing. Tracks such as “Beijing Evening News” (北京晚报) and “Hello Teacher” (老师你好), which featured catchy hooks and witty lyrics, soon became underground anthems in the capital. However, in 2015, no fewer than 17 of the group’s songs were wiped from the Chinese internet by the government’s Culture Bureau due to what the authorities considered “vulgar and violent content.”

This battle between underground hip hop acts and censorship organs who poorly understand the genre is one that would come to mark the following decade of rap in China.

—

Continue reading about the history of hip hop in China with part 2, in which a new generation rises to take Chinese hip hop to the next level, and a hit reality show makes the genre a mainstream phenomenon overnight:

The History of Rap in China, Part 2: Hip Hop Goes Mainstream (2010-2019)From humble origins as a niche pastime in constant conflict with the authorities, hip hop rises to become a mainstream art (and industry)Article Feb 08, 2019

The History of Rap in China, Part 2: Hip Hop Goes Mainstream (2010-2019)From humble origins as a niche pastime in constant conflict with the authorities, hip hop rises to become a mainstream art (and industry)Article Feb 08, 2019

You can also dig deeper into Chinese hip hop here:

Bohan Phoenix Injects a Dose of Reality into China’s Hip Hop Boom on New Track “YMF”“Chinese hip hop is a misleading title to me,” says the bilingual rapper trying to flip the table on dubious labelsArticle Jan 28, 2019

Bohan Phoenix Injects a Dose of Reality into China’s Hip Hop Boom on New Track “YMF”“Chinese hip hop is a misleading title to me,” says the bilingual rapper trying to flip the table on dubious labelsArticle Jan 28, 2019

Is Chinese Hip-Hop’s Honeymoon Over? Rap Crew HHH Quits Modern SkyArticle Nov 17, 2017

Is Chinese Hip-Hop’s Honeymoon Over? Rap Crew HHH Quits Modern SkyArticle Nov 17, 2017

“Aren’t You Bored?” Rapper J-Fever on Redefining his CraftArticle Mar 16, 2018

“Aren’t You Bored?” Rapper J-Fever on Redefining his CraftArticle Mar 16, 2018