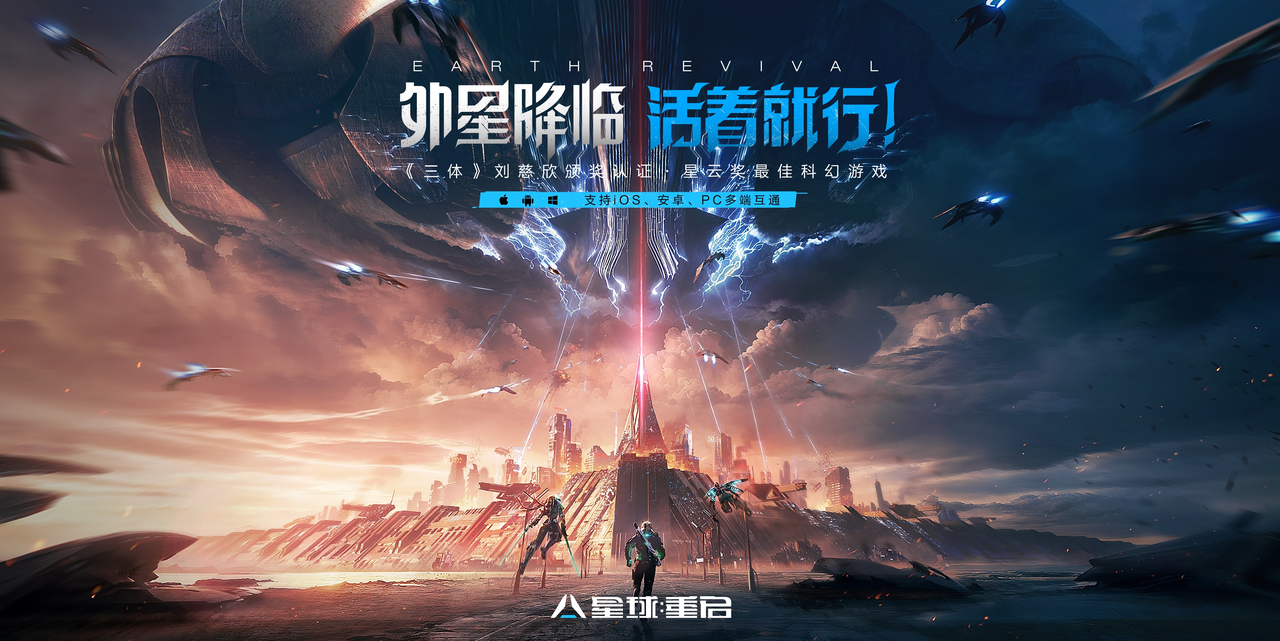

Chinese readers might remember those hyper-dramatic web novels crammed with CEO seductions, vengeful heirs, and secret aristocrats that used to dominate bestseller charts. The genre may have gone flat in China, but now American viewers just can’t quit bingeing similar rapid-fire dramas on an app called ReelShort.

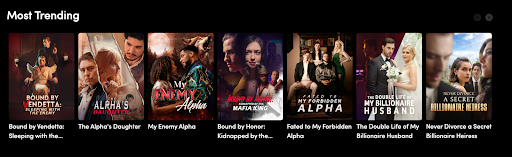

Titles like My Billionaire Husband’s Double Life and Son-in-Law’s Revenge certainly sound foreign. Yet it’s no coincidence they resemble China’s bygone online fiction craze.

The propulsive appeal behind ReelShort’s hottest rapid-fire dramas? Mostly recycled Chinese content, given California makeovers by a local subsidiary of Beijing-based media company COL Group before maximum drama extraction for American tastes.

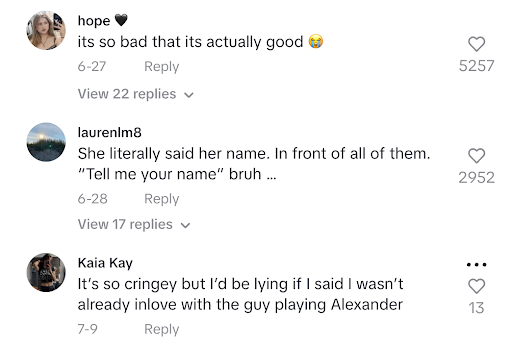

Yes, the same eye-roll inducing online novel tropes once so popular in China now arrive on Western screens with slight cultural translation tweaks. Pompous CEOs ensnaring innocent beauties, scheming heirs earning their richly-deserved comeuppance — every wish fulfillment box gets checked.

Somehow timeworn premises feel fresh when language setting changes. Through this adapted formatting alchemy, Chinese guilty pleasures are transformed into addictive new hits abroad.

The streaming model also drives bingeing. After sampling a few free episodes ending in cliffhangers, subsequent installments cost around 50 cents USD behind the paywall. Consuming one full series thus requires a $20-50 splurge — low enough to feed most compulsive viewing habits.

Yet ReelShort’s rapid growth defies assumptions about Chinese vs. Western tastes.

When ReelShort briefly seized the #1 US iOS entertainment app spot from almighty TikTok over the November 11th weekend, headlines portrayed it as an isolated underdog victory. But the milestone actually reflected this plucky Chinese story factory’s steady ascent up American charts.

Challenging assumptions about cultural translation barriers, ReelShort repurposes China’s well-worn melodramatic tropes for renewed addictive glory abroad. And it isn’t parent company COL Group’s first smash crossover — their earlier English story apps like interactive adventure game Chapters and romance portal Kiss both ranked highly as well.

Of course, Shein and Temu have also demonstrated Chinese digital goods can thrive overseas if priced alluringly. But ReelShort specifically extracts profits from recycled niche content, without Westernizing its production methods.

ReelShort’s rapid rise pushes back against the expectation that Chinese entertainment can’t translate, or that Western audiences would reject its outdated gender tropes. The app proves cultural barriers crumble when satisfying primal cravings for drama, wish-fulfillment, and cliffhanger resolution.

As digital platforms turn global, future media victors may be those best at unlocking those embedded human hooks across superficial cultural differences. Through that lens, China’s soapy reboot fever finding American fans reveals vast untapped potential for viral entertainment cross-pollination once we move past surface-level distinctions.

Banner image by Haedi Yue, other images via ReelShort.