Talks between Tesla and the Chinese government took over tech headlines last week. Why were these so important?

1. Tesla wants to build a factory in Shanghai

Tesla is trying to reach an agreement with the Shanghai Municipal government that would allow it to set up an electric car factory in Lingang development zone. If talks are successful, Tesla would be the first foreign automaker given permission to produce electronic cars on Chinese soil. If the assembling process is done in China, models like the Model S sedan and Model X sport utility vehicle can avoid a 25 percent tax, thereby allowing Tesla to lower its sales price and become more competitive in the Chinese market.

2. The China market is essential to Tesla’s global ambition

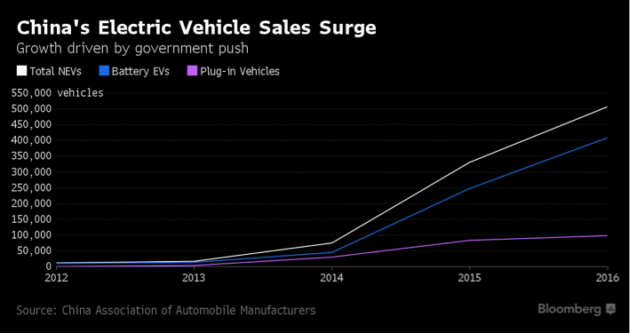

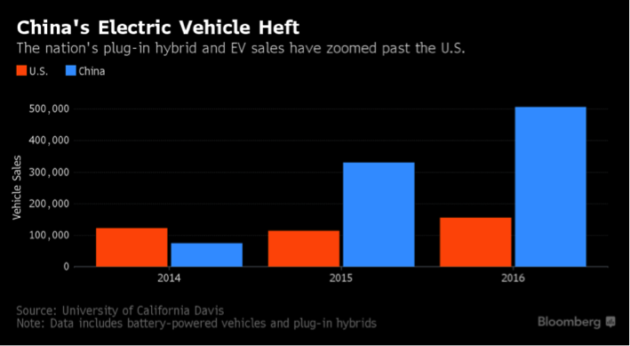

According to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, 507,000 new-energy vehicles, including electronic cars, were sold in China in 2016, and the country hopes to boost that number tenfold in the coming decade. According to Bloomberg, research shows China contributed to about 15 percent of Tesla’s $7 billion in revenue in 2016, almost double what it was in 2015.

3. Tesla needs to find a local partner

Tesla cannot enjoy this ride solo. In order to build its own factory in China, Tesla needs to comply with the law that requires it to find a local joint-venture partner. Tesla might be able to play around with it and have its fully-owned factory built in a foreign trade zone. However, the Chinese government recently announced a halt in issuing business licenses to auto manufacturers. Tesla does not have a license. Moreover, building a factory in a foreign trade zone means that Tesla will have to continue to pay the 25 percent import tax, which would defeat the entire purpose of manufacturing in China to begin with. Getting a local partner is the company’s only option. It is still unclear who Tesla will pick, though the best possibility is SAIC Motor, a state-owned auto manufacturer in Shanghai.

4. Everything about this is totally up in the air

On June 22, the photo below was widely spread online to prove that the talks were happening and an agreement is to be made. However, some Chinese reporters later raised suspicions about the reliability of the photo, pointing out that it shows neither signed documents nor credible people. The name tags say Shanghai Municipal Government and Tesla, but beyond that — nothing. The photo is far from persuasive.

Meanwhile, though their stocks have enjoyed a substantial bump due to the recent news, multiple Chinese auto companies, such as Lingang and Tianqimo, have publicly distanced themselves, saying that they have not yet been in touch with Tesla. In response, Tesla said in a recent statement that more details will be released toward the end of this year.