When Xun, who declined to give her real name out of privacy concerns, had her first menstrual period at 12, she was taught to use straw paper instead of sanitary pads.

Growing up in China’s Sichuan province, Xun lived upon just enough money for food and tuition. No matter how careful she was, straw paper would fall apart and easily leaked. Therefore, Xun only wore black pants during her period, and put a thick layer of used notebook paper on her chair to prevent it from getting dirty. Eventually, thanks to a monthly subsidy of 50RMB (about 7USD) and waived tuition, Xun started using proper menstrual pads from high school onwards.

Now at 33, Xun has become a vice president at a travel agency in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. Even with an annual salary of 250,000RMB (36,505USD) and little financial burden, she still tries to cut costs on sanitary products, for example, by buying in large quantities during discount seasons.

“I’ve personally experienced period poverty, though that was almost 20 years ago,” she says. “I know there are still a lot of women suffering what I experienced, or worse.”

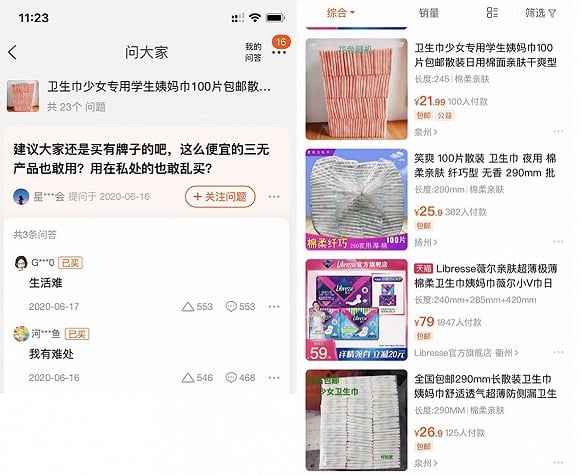

A post of 100 unbranded and package-free sanitary napkins recently aroused a heated discussion around period poverty on Chinese microblogging platform Weibo. The pads were being sold at 21.99RMB (3USD) on the country’s biggest ecommerce platform, Taobao.

In response to alerts about the pads’ dubious quality, two purchasers implied that they could not afford products with higher prices. Both users simply wrote, “Life is difficult.”

A screenshot of package-free sanitary napkins, on which buyers commented, “Life is difficult” (image: Taobao)

As of today, the hashtag “package-free sanitary pads” (#散装卫生巾#) has garnered more than 1.38 billion views on Weibo.

According to surveys from nonprofit organizations, millions of low-income women and girls in rural China are unable to purchase safe sanitary products. Poor menstrual hygiene puts their health at risk, and can sometimes be life threatening.

Think about it this way: assuming a woman uses at least 30 pads during each period and only buys normal daily-use sanitary pads, that costs a minimum of 1,040RMB (around 152USD) a year. For the more than 600 million people who earn less than 1,000RMB (146USD) a month in China, personal hygiene is probably the last thing they care about. With nighttime-use pads, period panties, and flex foam pads, pain relievers, and heating pads to soothe symptoms, the costs associated with monthly periods easily add up even for women in better financial conditions.

Even worse, due to period shame and lack of sex education, menstrual products are considered unspeakable, and overlooked as necessities for women.

Juan, 28, an elementary school teacher in a village of Hunan province in southern China who declined to give her real name out of privacy concerns, has seen many girls unable to use proper sanitary towels, especially those raised by single fathers.

“Because of the shame around menstruation, single dads are not willing to talk about it, nor give little girls money to buy sanitary napkins,” she says. “Sometimes teachers are the ones who buy for them.”

Related:

How This Chinese NGO is Changing Young Girls’ Attitudes Towards their BodiesBright & Beautiful’s programs reach young girls in rural China, where preferences for boys over girls still pervadeArticle Jun 01, 2020

How This Chinese NGO is Changing Young Girls’ Attitudes Towards their BodiesBright & Beautiful’s programs reach young girls in rural China, where preferences for boys over girls still pervadeArticle Jun 01, 2020

Women with periods are seen as “dirty” according to traditional beliefs. For example, women are not allowed to honor the dead during menstruation. When Juan’s grandmother passed away, she was forbidden to worship in the hall or touch anything because “dirty things are an offense to God.”

“I was a little upset at the time, but I was convinced that menstruation was dirty. I believed I shouldn’t go,” Juan says. “I prayed for my grandma from my heart and asked for forgiveness. I’m sure that she will forgive me.”

The taboo has become a custom. Yet though Juan still follows the rule, she says, “If I had a daughter, I wouldn’t stop her from going.”

Chinese people have also nicknamed menstrual periods in multiple ways to avoid saying it out loud. It’s often referred to as having “fallen into misfortune” (倒霉了) , “auntie” (大姨妈), or “official holiday” (例假) in Chinese. In the poster of a popular Indian film released in China in 2018, Pad Man — in which an Indian entrepreneur invents a better and more affordable menstrual pad — translated the film’s name to Indian Partner, and exchanged the pad held in the main character’s hand with white paper.

The lack of sex education also contributes to the stigma around periods. A 2012 survey of 1,593 teenagers ages 14 to 17 shows that 73.5% believe that they barely receive sex education at school, while 86.6% said that they rarely get sex knowledge from their parents. Many Chinese women also still believe they can lose their virginity by using tampons — as of 2016, only 2% of women nationwide had used them.

“I never received any sex education as a kid,” says Wang, 26, who asked that we only use her last name. “I didn’t start wearing underwear until the fifth or sixth grade. I only started buying and wearing bras when I saw other girls of the same age wear them in middle school. I didn’t know people had sex until my third year of high school. That’s a really late sexual enlightenment.”

Wang says she had to change sanitary pads every one or two hours during her teenage years due to heavy period flow. To save money, her mother taught Wang to pad them with toilet paper. However, Wang says the discomfort caused her to walk awkwardly, and she was mocked by her male classmates.

“My mom also put toilet paper on top of her pads. She didn’t know that it would hurt your body — she didn’t have the knowledge,” Wang says.

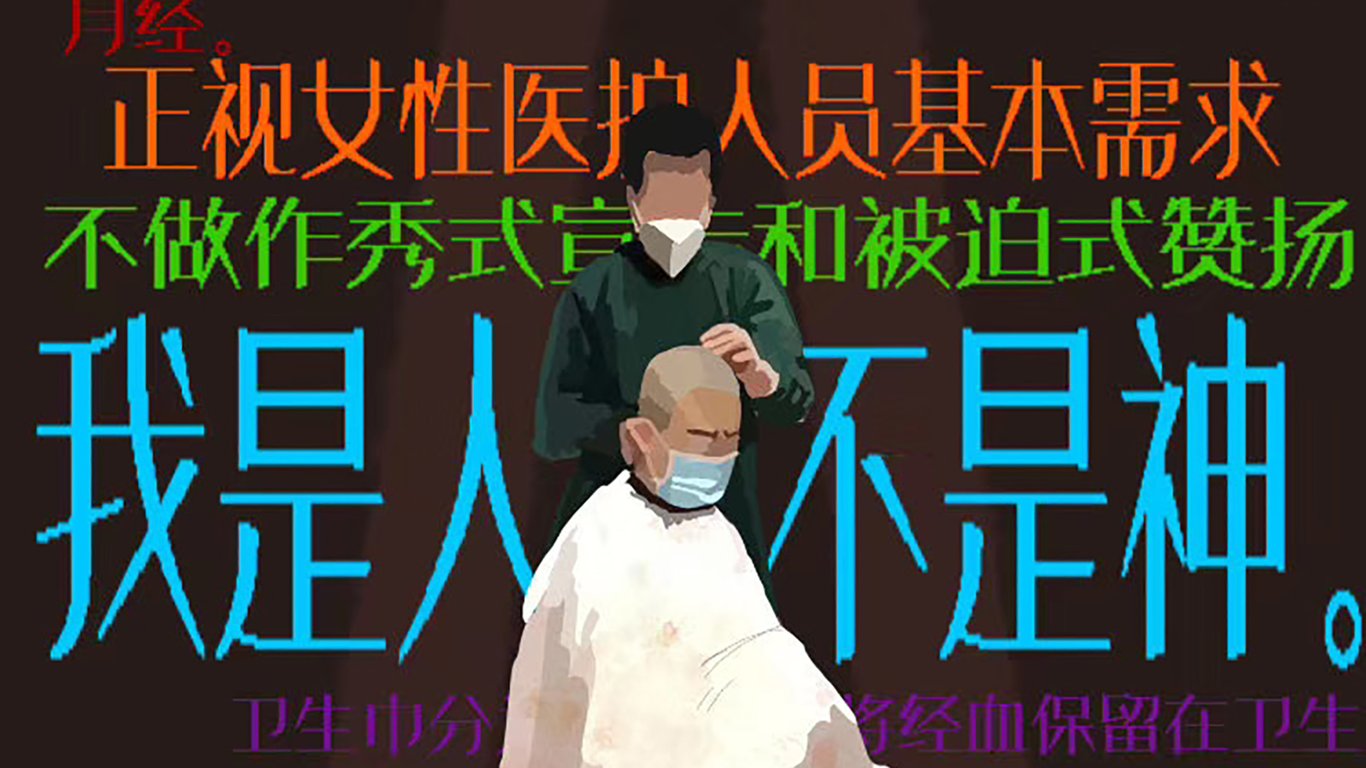

Efforts to normalize and destigmatize menstruation have gradually rolled out in response. In early February, activists and volunteers were calling for feminine hygiene products to be provided for female frontline doctors and nurses in Hubei province, the center of the Covid-19 outbreak. As demands for greater attention to women’s needs grew, female medical workers themselves started openly talking about their experiences.

Related:

“Don’t Touch My Hair”: Nurses’ Shaved Heads Spark Controversy Over “Sexist” Coronavirus CoverageNetizens are bashing an online video about women nurses in a media landscape that only shows “women’s sacrifice”Article Feb 19, 2020

“Don’t Touch My Hair”: Nurses’ Shaved Heads Spark Controversy Over “Sexist” Coronavirus CoverageNetizens are bashing an online video about women nurses in a media landscape that only shows “women’s sacrifice”Article Feb 19, 2020

“I’ve asked my leader [for menstrual products] but was not approved,” female doctors and nurses were quoted as saying. “My colleague’s blood and urine flow together today — it’s too difficult.” Feminine hygiene products were eventually treated as essential goods in Hubei and delivered to frontline hospitals. More recently, students at a Chengdu high school raised the equivalent of 17,500USD for menstrual pad donations to rural areas, according to CGTN.

Xun believes that period poverty should not be discussed secretively, and hopes this wave of attention can lead to actual support from the government.

“The more people discuss, the more attention period poverty will get,” Xun says. “Hopefully there will be policies implemented to solve the problem — or at least, it will educate more people and encourage them to help poor women.”

Header image: Annika Gordon via Unsplash