China might be the country whose international identity is most synonymous with martial arts. From classic kung fu flicks, to Shaolin monks, to ancient, white-bearded masters, so many things that scream “China” all link back to fighting and combat arts. So why is China nearly completely absent from the international dealings of mixed martial arts?

MMA is now among the fastest-growing sports in the United States, and has major players, organizations, and histories in countries from Brazil to Japan. China, on the other hand, has remained relatively out of the picture.

Part of the explanation for this is historical. In the early 20th century, the Brazil-based Gracie family was already absorbing and adapting Japanese systems of judo into a new style, Brazilian Jiujitsu, which would go on to form the foundation for modern MMA.

In the ’80s, Japan was experimenting with its own highly-modernized style of martial arts, Shooto, combining elements of kickboxing, grappling, and wrestling.

By the ’90s, the United States bore witness to the first ever “Ultimate Fighting Championships”, a bareknuckle tournament pitting martial artists of different styles against each other (which would be won by Royce Gracie, cementing his family’s form of jiujitsu as a fundamental art of modern sport combat). Other countries like Thailand and Russia drew from their own full contact fighting traditions, and soon had their own stars, systems, and key players on the world stage.

But China didn’t get to participate in any of that.

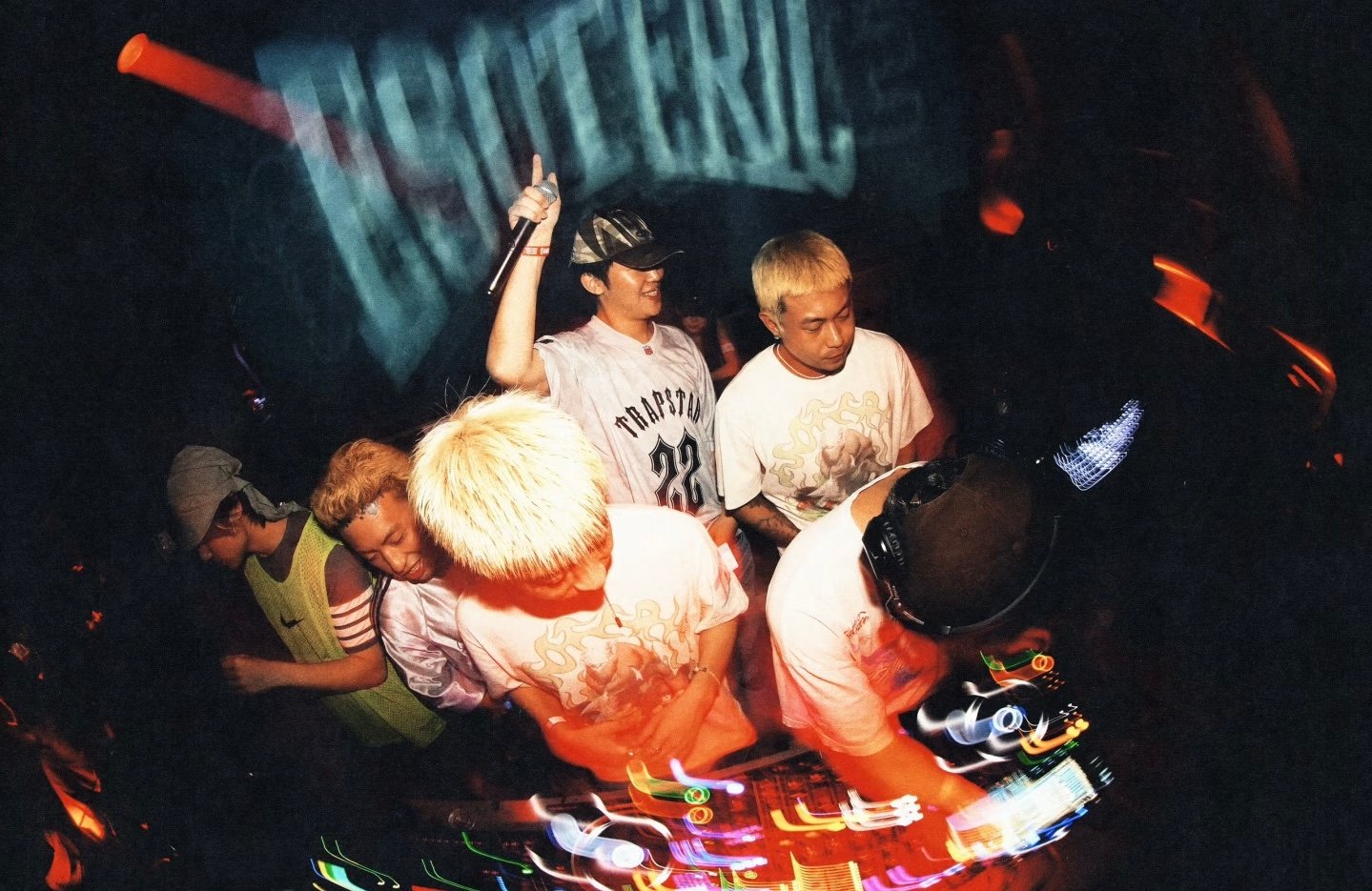

Wang Guan at UFC Shanghai via GIPHY

During the Cultural Revolution, practice of martial arts was banned as part of the campaign to purge traditional culture. Replacement arts emerged, namely, modern wushu, which put an emphasis on performance and demonstration of solo technique. By the time MMA was achieving a swing and becoming and honest-to-goodness sport, China had already cleansed itself of much of its combat culture, and wasn’t yet affluent enough to concern itself with the newly emerging form of sport fighting.

To top it all off, MMA’s brutally honest, results-driven philosophy fundamentally clashed with Chinese ideals of scholar-warriors and martial virtue. China wasn’t ready to accept MMA on a cultural, historical, or economic level. But today, that’s changing.

Cissy Long works at ONE Championship, Asia’s largest sport media property, and the largest MMA organizer in China. She says that MMA in China is still very much in its infancy, but that they are seeing an audience for it:

“MMA isn’t a mainstream sport yet, but it’s growing very quickly. Our championship in Shanghai’s Oriental Sports Stadium last year reached maximum capacity, with about five hundred fans outside still trying to get in. Even at our Changsha and Hefei events in 2015, in two non-first-tier cities, we reached full capacity. The sport here is still growing, but right now it’s only the beginning.”

Last November, UFC held its first-ever mainland China event in Shanghai. The Ultimate Fighting Championship had worked its way up, having previously thrown three events in Macau. It was a big step for UFC, and for international MMA in general. The long-awaited appearance of MMA’s biggest brand in the notoriously tricky mainland sports market seemed to represent a change.

“You can see the trend, with international organizers all trying to enter the market and carve out a slice of the cake,” says Long. “And you can tell that government officials are welcoming that movement.”

UFC’s China Debut Points to Promising Future for Chinese MMAArticle Dec 03, 2017

UFC’s China Debut Points to Promising Future for Chinese MMAArticle Dec 03, 2017

Generally speaking, MMA still holds a negative reputation in the mainland. This is due in part to the nature of the sport, and in part to its portrayal in media. Last year, Chinese MMA fighter Xu Xiaodong launched a high-profile crusade to prove the inefficacy of traditional Chinese martial arts, offering an open challenge and cash prize to any traditional martial artist who could defeat him. A resulting match with tai chi master Wei Lei went viral, ending in a matter of seconds. The tai chi master looked to have never received a punch before, and crumbled without delivering a single blow.

The incident rocked China, and upset fans of traditional martial arts. Xu himself became the subject of public ire, receiving threats and a 100 million RMB bounty on his head for any Chinese martial artist who could defeat him. Eventually the government became involved, blocking his Weibo account and executing police raids on further fights. Long cites boastful fighters such as Conor McGregor and Nate Diaz as further bad PR for the sport in China, where sports stars are expected to be more humble.

Meanwhile, on the fighters’ end, infrastructure and pro support haven’t quite reached an international level. MMA isn’t an Olympic sport, so it’s mostly overlooked in terms of large-scale financial support from the government. Outer cities tend to lack the high-level training and pro experience necessary to mold competitive fighters, and in major cities such as Shanghai and Beijing, MMA gyms are treated more as a fitness fad to cash in on than a serious hub for professional athletes.

Rex Huang takes the win at Animal Fighting Championship II in Shanghai.

Rex Huang is a pro fighter born in Taipei and fighting out of Shanghai. He equates China’s nascent MMA scene to the early days of Gracie dominance in the US, before the sport’s methodology was distilled to a science:

“Right now, we’re still in the Gracie era here. There are fewer MMA and jiujitsu schools here geared towards professionals. Most gyms are just there to make money, or teach one specific discipline like boxing or Muay Thai. I can only think of a few gyms in Shanghai that I would say really know what they’re doing.”

As a breeding ground for world-class fighters, China still has lessons to learn. But it hasn’t stopped a few breakout Chinese stars from taking hold, at home and internationally. China has a wealth of combat traditions to choose from, and practitioners of arts such as sanda kickboxing or traditional wrestling have found the jump to MMA to be a relatively easy one.

Athletes like Li Jingliang have formed the first wave of professional Chinese fighters, riding their success to top-tier international training sites, and hopefully bringing some of those lessons back home.

“In the US, the biggest difference is that you really get to know what pro fighters should do in the ring, and what they shouldn’t do,” Li told press after UFC’s inaugural China fight. “It was incredibly valuable for me to spend those two months training there, and the difference compared with the kind of training we have in China is huge… this is my responsibility — to train with the best, and be the best.”

With fans, too, the sport is catching on, and the supply of MMA talent can only grow to meet that demand. Huang believes China will grow into a major player internationally:

“Most people I talk to understand MMA, actually. Usually they can name some Chinese stars, or have seen bit at least once on CCTV. China is still relatively conservative with these kinds of things, but it’s changing for sure. A decade ago, there weren’t many fighters or organizations in China with the financial backers they have now. MMA in China will definitely be huge — I think it could be as big as Brazil or Russia.”

With officials now welcoming international organizations, fighters working harder than ever to build a competitive fight culture, and fans rapidly opening up to the relatively new form of sport combat, China might be set to achieve an MMA presence sooner rather than later.

UFC Shanghai Fight Night photos provided by UFC.