Editor’s note: This article by Jason Li was originally published on 88 Bar, and has been re-posted here with permission.

After much fanfare, I had a chance to visit the two opening exhibitions at the new Design Society 设计互联 in Shenzhen — “China’s first design museum.” Freshly unveiled last December, Design Society is located at the newly-constructed Sea World Culture and Arts Center in Shekou, one of the most historically-progressive areas in Shenzhen. That it is operated by long-time Shenzhen pioneer China Merchants Group and co-founded by the venerable, London-based V&A Museum makes this new space an enigmatic institution to say the least.

The building that houses Design Society is gorgeous — full of interesting angles and minimalist white space. Designed by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki and his firm (Maki and Associates), the Sea World Culture and Arts Center is fronted by Design Society on its first two floors but offers plenty of space upstairs for other tenants from the arts: galleries, education centers, bookstores and the like.

Exhibition 1: Values of Design

Organizers spared no expense when it came to this first show curated by the V&A’s very own Brendan Cormier. They designed and renovated the space to match the show, using various custom-built walls and panels, display cases and signs to guide museum-goers through various themes (or “values”) around design.

As the Design Society website states: “The first exhibition… will consider how values drive design and how design is valued, as well as highlighting the key role that design plays in society.” Unfortunately, what constitutes a value or why these specific values were chosen is not revealed.

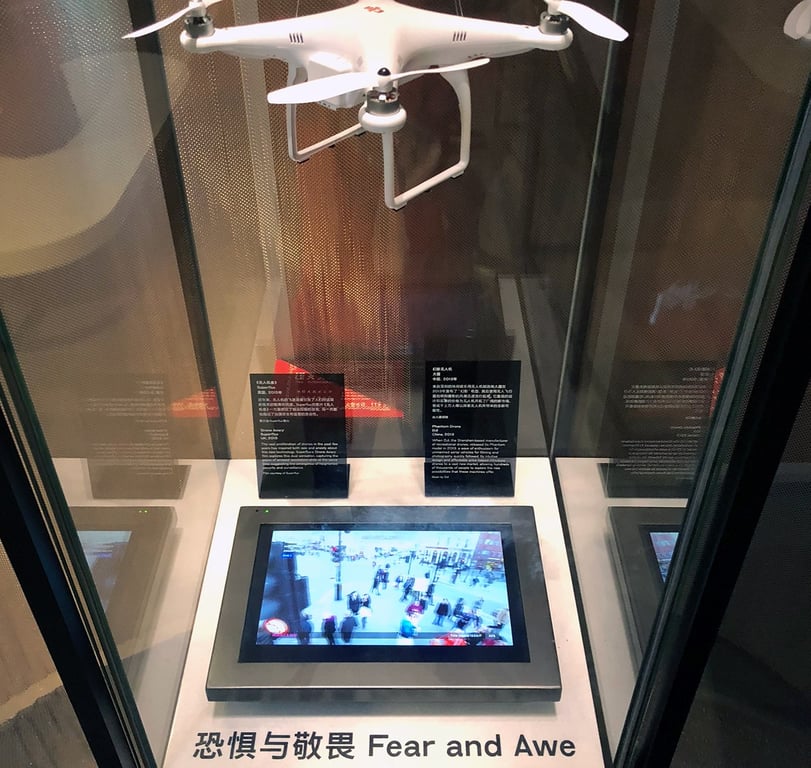

The story of each value is told through two or more contradictory designed objects: for “The Impossible,” a 1980s talking teddy bear was juxtaposed with the 2007 Apple iPhone; for “Fear and Awe,” a consumer-friendly DJI drone was juxtaposed with video art about the dystopian surveillance power of drones. This format provokes thought by letting the objects speak for themselves, and showcases the depth and breadth of the V&A’s 100+ year-old collection from around the world.

However, “Values of Design” is chopped up into dozens of values, which themselves are bucketed into larger categories (“Cost, Identity, Materials…”), making the visiting experience an extremely fragmented one. As with the opposing notions of drones-as-surveillance versus drones-as-toys, issues are quickly raised and promptly dropped within the span of a few objects.

The overall impression then is that of flipping through an incredibly well-curated Industrial Design 101 coffee table book: great for curious outsiders, but offering very little to provoke or inspire those of us in the field.

Exhibition 2: Minding the Digital

Design Society’s second inaugural exhibition, “Minding the Digital” was curated by the gallery’s own Carrie Chan. More forward looking than “Values of Design,” this exhibition is meant to “[inspire] people to meander through the creative possibilities of the digital future and navigate between technology-oriented and human-oriented approaches.”

As such, it comprised various design-as-art and technology-as-art projects from academics and artists from around the world, with a special emphasis on works from Mainland China and Hong Kong.

Many interesting, interactive works were on display – a dress that morphs in response to sound, sculptures that can only be generated by digital algorithms, structures that mixed new and old manufacturing techniques, and so on. Unfortunately, these projects were interrupted by gauche light-projected prompts asking museum-goers mock-provocative questions like “can interaction be designed” or “can empathy be designed.”

Shenzhen Story Prevails

Despite their differences, the story of Shenzhen was visibly present throughout both exhibitions as well as in the museum store. In “Values of Design,” the city was well represented within the collected objects, which included a Shanzhai iPhone, a Tencent photo device and even a Shenzhen secondary school uniform. In “Minding the Digital”, the narrative was even more prominent: Shenzhen startup poster children Seeed Studios and Chaihuo Makerspace were both present, and there was even a section devoted to Open Data and Open-Source Hardware. Last but not least, the store outright celebrated the Shenzhen story by selling fridge magnets with classic slogans such as “Time Is Money” and “Shenzhen Speed.” (These were admittedly pretty great.)

Based on these inaugural exhibits, the new Design & Society gallery shows signs of promise, but is ultimately off to a slow (and artistically reserved) start. Given the history of grand experiments in Shekou and Shenzhen, I had hoped for bolder, more provocative shows rather than two high-level surveys about design. But perhaps, its experimental nature comes not from its curatorial program but from its organizational roots: Design Society is the first ever museum collaboration between a Mainland Chinese corporation and an international arts institution, which is no small feat given China’s increased resistance towards foreign institutions.

You might also like:

How WeChat Became the First Chinese App Entered into a Museum CollectionArticle Jan 20, 2018

How WeChat Became the First Chinese App Entered into a Museum CollectionArticle Jan 20, 2018

Chinese Art Provokes Innovation, Protests and Censorship AbroadArticle Sep 28, 2017

Chinese Art Provokes Innovation, Protests and Censorship AbroadArticle Sep 28, 2017

New Joint Projects with Google, V&A Museum Legitimize Tencent on World StageArticle Jan 20, 2018

New Joint Projects with Google, V&A Museum Legitimize Tencent on World StageArticle Jan 20, 2018