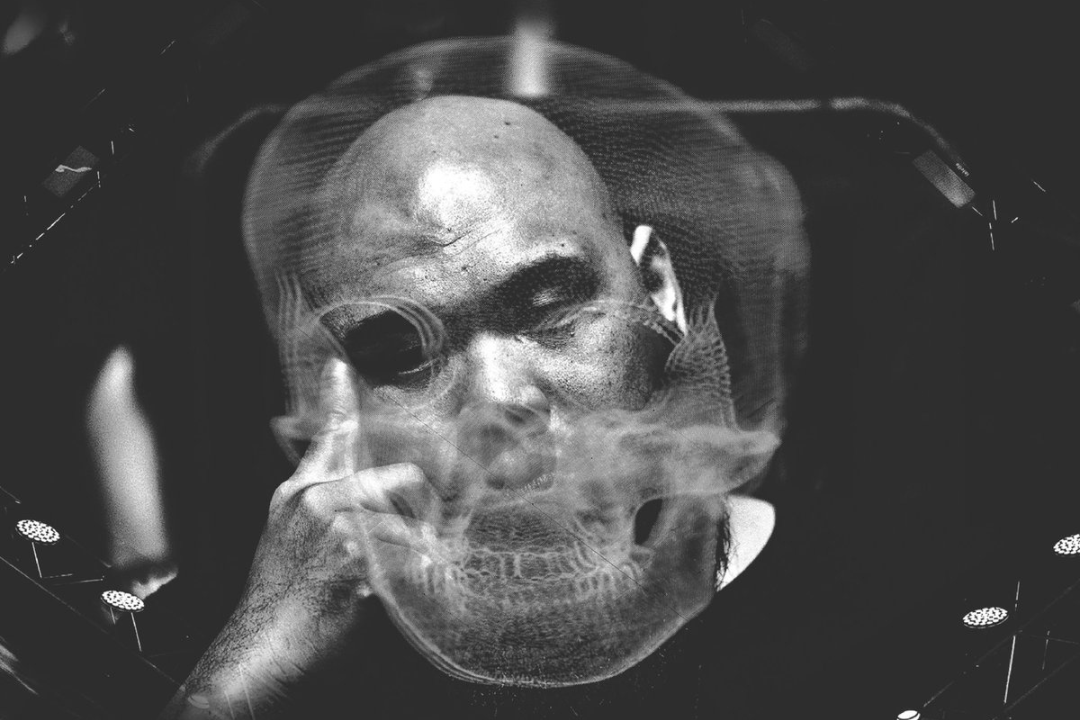

Into the Night is a series exploring China’s vibrant nightlife and music scene and the roster of young people that make parties in the country so damn fun. This story introduces Chengdu-based hip hop producer Eddie Beatz.

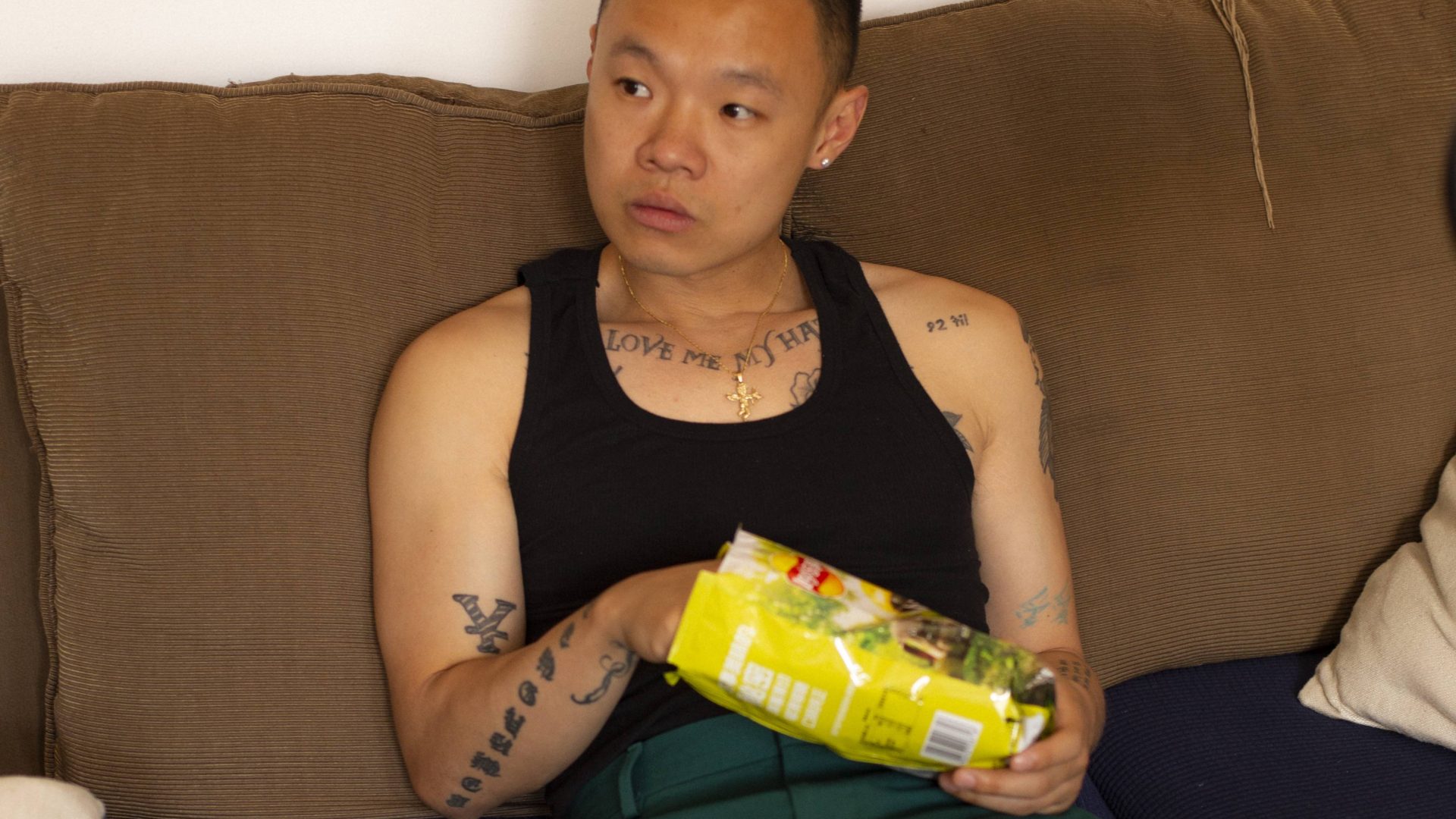

“The difference is that life is more relaxed here,” Chengdu hip hop producer Eddie Beatz tells us about the city. “When I go to Shenzhen, people talk about work, housing prices, and other financial things. In Chengdu, because it is so casual, you can really sit down and talk about music, talk about a record, or what you have been listening to lately. That’s an experience that friends in other cities rarely have.”

Beatz draws on his own experience to sum up the city in three words: freedom, rebelliousness, and wildness.

Lying at the center of China, in the vast province of Sichuan, Chengdu straddles somewhere between the shiny new metropolises of the eastern coast and the hinterlands in the far west of the country, a meeting point for China’s minority cultures.

He tells us that Chengdu’s air of freedom and wildness is down to lower rent prices, more financial freedom, and a general lack of strictness concerning musical performances compared to other Chinese cities.

It is, then, the perfect city for someone like Beatz to make music stress-free.

His first musical effort was for a girl he liked when he was in the sixth grade. Looking back on how the object of his affection reacted to this song, he opines that she was probably just as embarrassed as he was because, “In those days, people thought rap was really stupid.”

This was before the explosion of popularity that rap and hip hop music have experienced in the past decade or so.

Speaking about how he became enamored of rap music at such a young age, he tells us, “Because I sing out of tune, rap was more impactful for me. It felt more direct and suitable when I was a kid.”

His expectations for his music are relatively meager, as he tells us that his aim is simply to “be happy making music every day.”

On the other hand, his approach to making music has changed considerably through the years. When he began his musical career, he came up against the kind of difficulties that those working in the arts usually face.

“I had no job and no income, and people in my family were constantly asking me whether I could support myself with music,” he tells us. “At the same time, I wanted to buy lots of things that I couldn’t afford, and I wanted to eat a lot, like, for example, I would invite friends to go with me to these great restaurants, and then after looking at the menu, I wouldn’t know what to eat.”

One of Beatz’s more impactful encounters was when he met an unnamed Grammy-winning producer visiting Chengdu to hold a symposium. Through the meeting, Beatz learned that the decorated producer spent eight hours per day making music, considerably more than the two or three hours he spent producing tunes daily.

This insight had a significant impact on Beatz, who decided, as a result, to increase his own productivity. He began spending eight hours each day making music, and he began to feel that his work was becoming more rewarding, as he was making more music and feeling a stronger sense of accomplishment.

The scope of this work is changeable, as he can spend as much as six hours simply listening to music and two hours creating music.

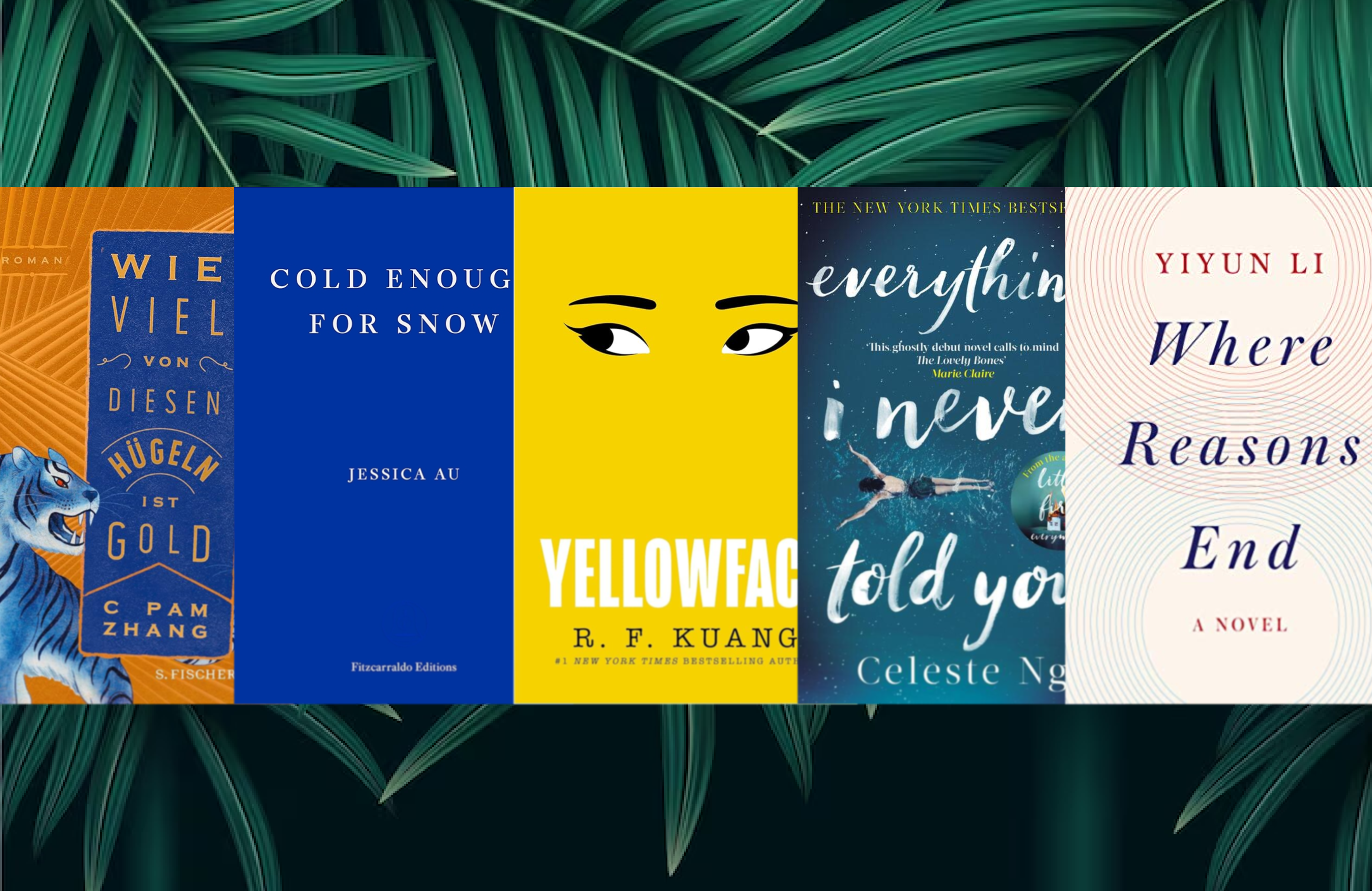

It’s a strategy that has borne fruit for him. In 2021, he collaborated with much-loved rappers J-Fever and Zhou Shijue (周士爵) on the excellent Xīn Yù Pínlǜ (心愈频率), which loosely translates to ‘Heart Rate.’

Just this year, he released Yěshì Lán (也是蓝 or Also Blue). The jazzy, experimental release draws on Beatz’s vast abilities and interests and brings together some phenomenal collaborators, such as Higher Brothers’ Masiwei, Shanghai singer-songwriter Voision Xi, Xi’an rap legend Pact, and regular collaborators Zhou Shijue and J-Fever.

The name of the record seems to recall the melancholic and romantic vibe of a record like Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, but Beatz refutes this, saying that the color blue here can “be a taste, a color, or something that looks good.”

He goes further and tells us that the name has a somewhat comical meaning, “Because my Mandarin is not standard, sometimes my friends can’t tell the difference in what I say between 蓝 (blue) and 难 (difficult), and they joke with me about this. While making this record, I felt that life was too difficult.”

The diversity of styles at play on Yěshì Lán reflects the collaborations that Eddie Beatz has been a part of throughout his career.

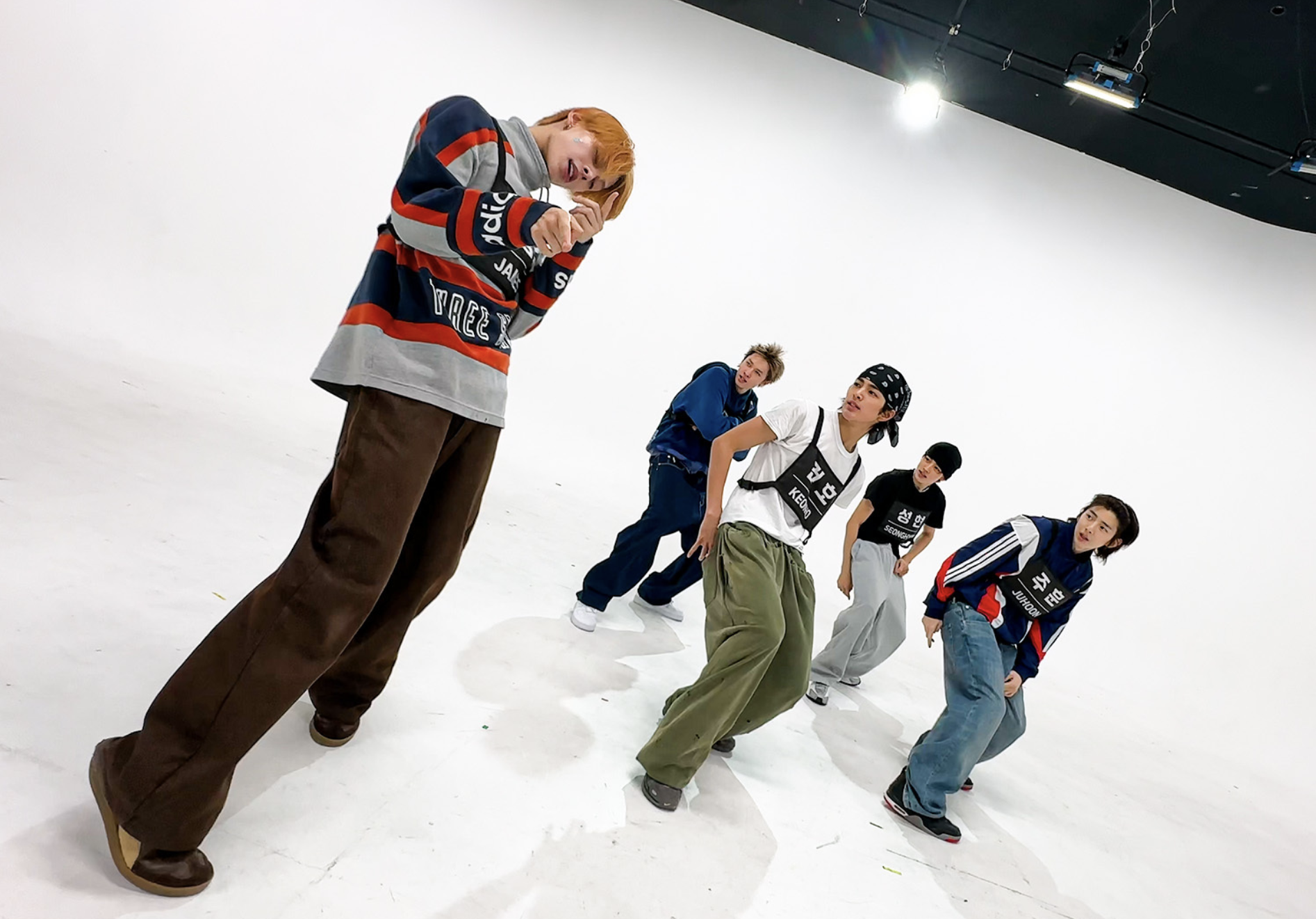

As a Chengdu resident, he witnessed the phenomenal rise of trap music in the city. He speaks to the incredible popularity of the Chinese hip hop variety show The Rap of China and how much influence that had on the city’s music scene and his own career.

“Maybe six, seven or eight years ago, everyone would sit around together thinking of a way to find a job. When the show came out, everyone changed from wearing flip-flops to buying countless pairs of shoes,” he says.

“Before that, buying a house or a car was unthinkable, and now rappers have a lot of cars and houses. From my point of view, I feel like I’m dreaming, because yesterday, everyone was sitting together drinking a Sprite, and now many of them are in the elite class.”

With that being said, Beatz remains a lowkey figure, someone who is driven to create alongside experimental rappers and musicians like J-Fever and Voision Xi. Take a look at his Netease Music page (a Chinese equivalent to Spotify), and you’ll also find a range of remixes and piano-based releases.

“I have participated in freestyle activities, but I feel that I am a relatively introverted person. After I finish performances, I think back on it and feel stupid and won’t want to perform anymore. For me, making music behind the scenes is the best.”

“I feel like my releases don’t need to be talked about; the music that I release is representative of my wish to show people that music is beautiful.”

Cover image designed by Haedi Yue; other images from ‘Why This Chinese City Produces More Rappers Than Any Other,’ episode two of RADII’s mini-doc series ‘Into the Night’