If Bruce Lee—also known by his Chinese name, Li Xiaolong—were still alive today, he would soon be turning 85. Yet his influence remains global and deeply rooted, especially among teenagers in the U.S. and Europe. From gym classes to film schools, from martial arts dojos to pop culture references, Bruce Lee’s philosophy and style have transcended generations. For many young people, especially in Western countries, Bruce Lee was their first introduction to Chinese martial arts, philosophy, and culture—forever altering the Western image of the Chinese man, once stereotyped as weak or passive.

Lee’s filmography is equally impressive. Beyond his iconic roles in The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, Way of the Dragon, and Enter the Dragon, his brief role in the American TV series The Green Hornet was pivotal in showcasing an Asian man as a strong, intelligent hero to U.S. audiences.

Despite being a legend in the Chinese community, Bruce Lee candidly admitted in a 1971 interview that he could not speak Mandarin fluently—though he acted in Mandarin-language films such as The Big Boss. This adaptability and flexibility were not only present in his career but also became the core spirit of the martial art he created: Jeet Kune Do. “This also reflects the philosophy of Jeet Kune Do. It is about intercepting,” the legend explained.

Jeet Kune Do (JKD) is a martial art and philosophical framework developed by Bruce Lee that emphasizes adaptability, directness, and simplicity in combat. It is not a rigid style but rather a method for practitioners to develop their own effective fighting approach, incorporating techniques from various martial arts with a focus on practicality and efficiency.

It might sound abstract in text, but this clip from Longstreet offers a more vivid explanation:

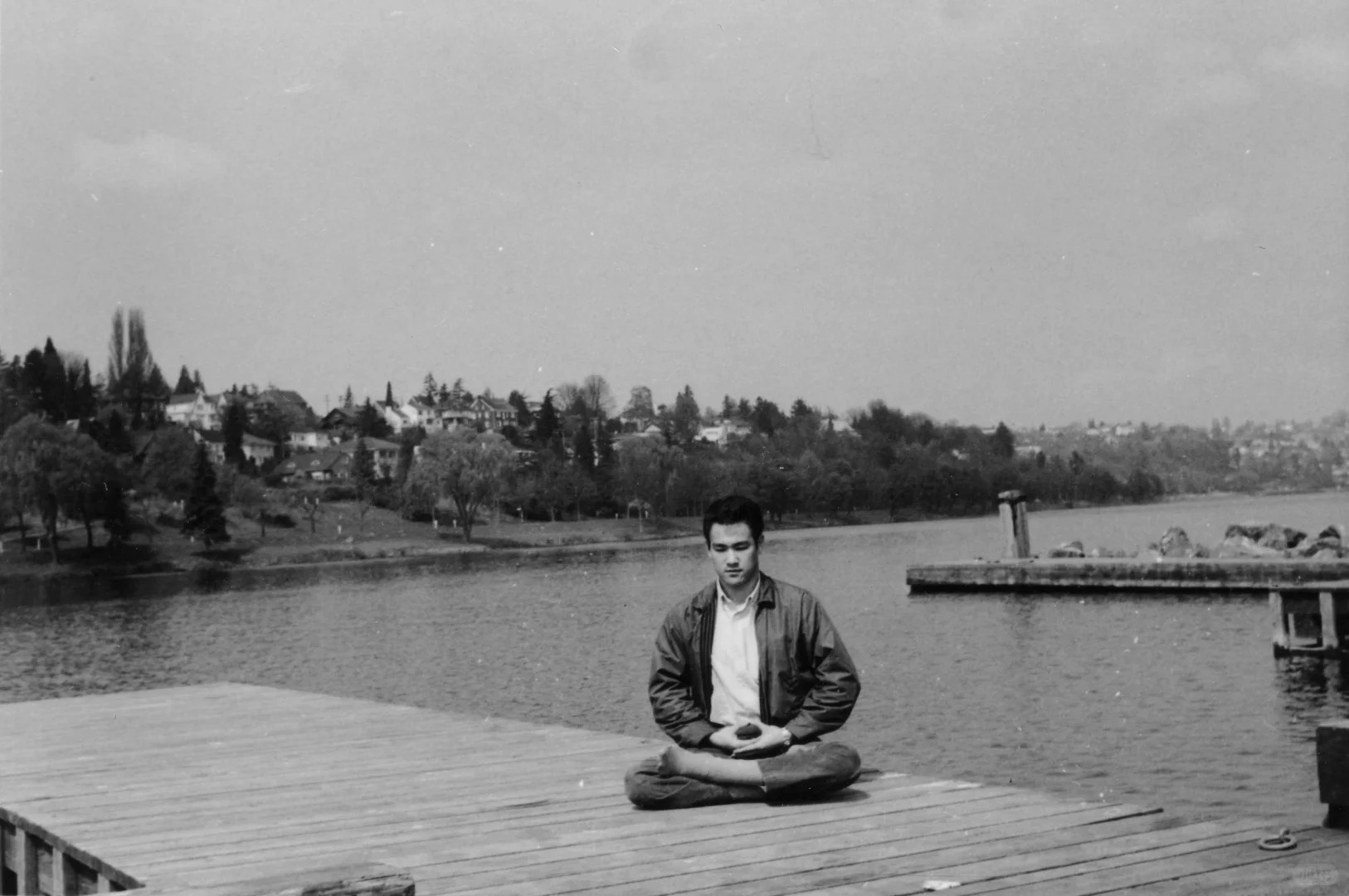

One of the core features of Jeet Kune Do is fluidity. As Lee famously said in 1971: “Be water, my friend.” This concept aligns with the teachings of Laozi in the Dao De Jing: to unlock one’s full potential and express oneself honestly, one must become formless, adaptable, and ever-flowing—like the Dao itself. In Daoist philosophy, the contrast between “有” (being) and “无” (non-being) highlights that true power often lies in emptiness and openness, enabling constant transformation.

Another key element is embracing life through an awareness of death—an idea resonant with Nietzsche’s concept of self-overcoming. The “art of dying” in Jeet Kune Do is really an “art of flow:” by letting go of attachment to the past, including ambitions, ego, and outdated values, we can continuously renew ourselves. Nietzsche called this process the creation of new, higher values through self-reinvention. In this sense, “dying” is a metaphor for transcending old selves and achieving rebirth — a philosophy at the heart of Lee’s practice.

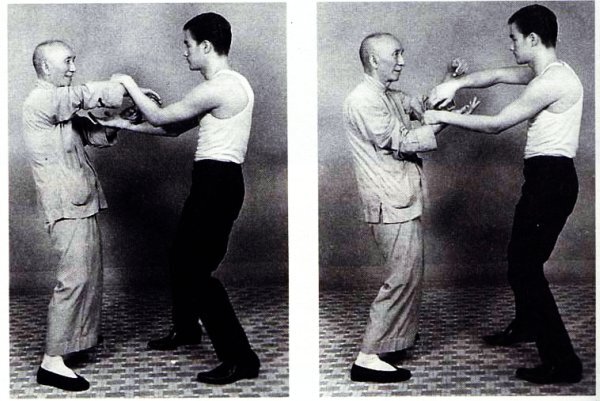

Naturally, Bruce Lee’s ideas drew criticism from traditional martial arts circles. Many considered him a rebellious force against orthodox traditions. This tension crystallized in a pivotal moment in 1964, when Lee received a letter from elder Chinese martial artists in San Francisco who opposed his teaching of kung fu to non-Chinese students. Back then, in a highly discriminatory American society, Lee’s decision to teach Westerners was radical, breaking boundaries that had long excluded non-Chinese practitioners.

Faced with a formal challenge from a kung fu elder named Wong Jack Man, Lee accepted. His wife Linda later recalled the event: “In the initial exchange, Wong Jack Man ran around the room, exiting and re-entering several times, with Bruce chasing him relentlessly. Eventually, Bruce pinned him to the floor, shouting in Chinese: ‘Do you give up?’ He repeated it until Wong admitted defeat. The fight lasted about three minutes. While Bruce technically won, he was deeply dissatisfied. He was exhausted, out of breath, and frustrated that his techniques hadn’t been as efficient as he wanted. That fight sparked Bruce’s determination to evolve his training, ultimately giving birth to Jeet Kune Do.”

Tragically, Bruce Lee died young at just 32 years old. Officially, his death was due to an allergic reaction to aspirin, though legends persist of an ancient curse on his Hong Kong home. Some point to the untimely death of his son Brandon—who was fatally shot with a prop gun containing a live round on the set of The Crow in 1993—as further “proof” of the supposed curse.

Had Bruce Lee lived to see today, he would witness countless people worldwide practicing Jeet Kune Do. The style even appears in anime: in Detective Conan, it is a recognizable trait of the character Subaru Okiya, whose true identity is Akai Shuichi. Yet Lee’s most lasting legacy is his synthesis of Eastern and Western philosophy, and his ability to blend traditional and adaptive martial arts in ways that continue to resonate across cultures.

It’s fitting, then, that Lee’s gravestone in Seattle bears the yin-yang bagua symbol, representing balance and flow. These qualities are what make Bruce Lee’s legacy eternally compelling to young people everywhere.

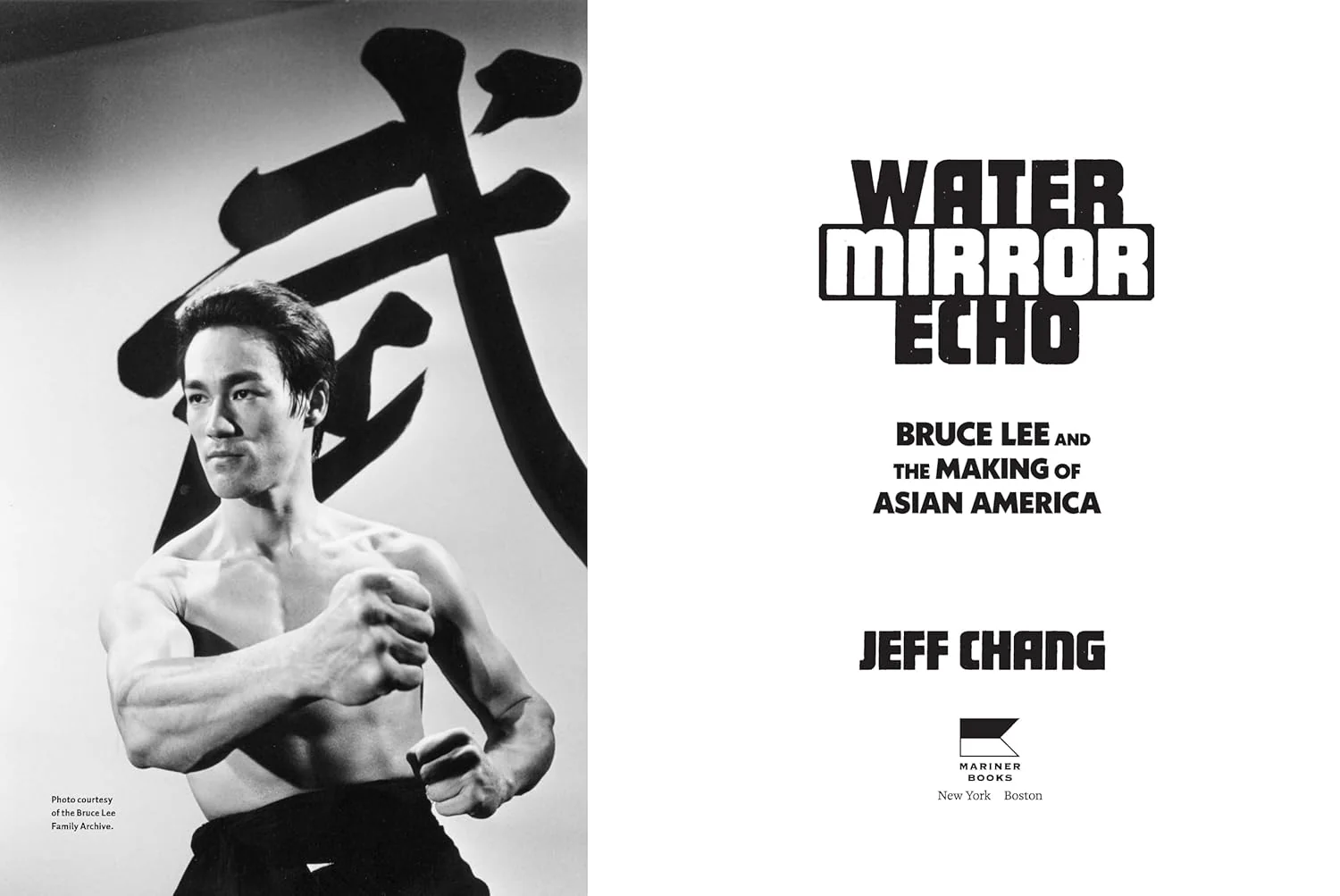

Cover image via Mind Body Spirit.