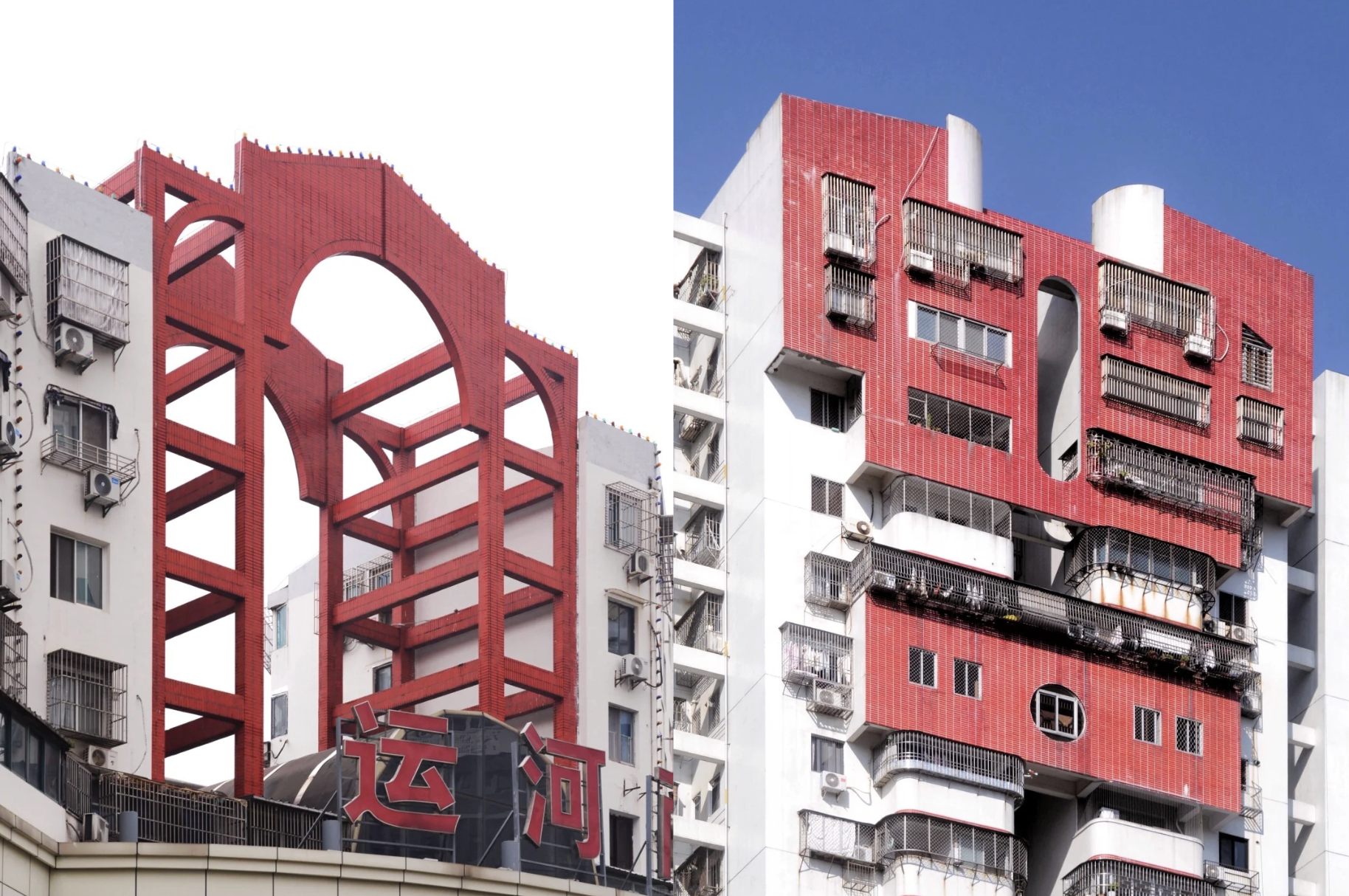

Spiraling staircase, reflective window panes, and disk-shaped silhouettes dotted the skylines of Chinese cities in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s. It was a time defined by a funky, futuristic maximalism—an aesthetic that embodied the nation’s optimism at the turn of the century. In an era of rapid technological growth and the dawn of the internet, this distinctly Chinese architectural style was like an old Casio watch: unapologetically retro-futuristic.

Today, many of those once-dazzling structures stand weathered and rusting, replaced by sleek, minimalist designs. Yet one photographer is determined to preserve the beauty of these fading facades: 铁合西街东 (Tiehexi Street East). The name he goes by references a small dead-end street in his hometown, a nod to his artistic mission to share the overlooked structures of modern China, frozen in time.

RADII spoke with Tiehexi about his decade-long journey in photography, his architectural eye, and his obsession with reviving the lost aesthetics of the turn of the century.

Nostalgia for a Future that Never Came

Tiehexi wasn’t even born yet when most of these buildings were constructed. As a member of Generation Z, his fascination with the 2000s might seem unexpected, but it’s proven to be a part of a broader cultural wave in China.

In recent years, “Dreamcore” videos have spread like wildfire across Chinese social media. These short clips, often captioned “You wake up, and it’s 2008…,” are paired with soothing music, foggy and filtered photos of early 2000s living rooms, classrooms, video games, TV programs, and more. The top comments tend to sound something along the lines of “You can go back, but there will be no one there.” It’s a collective yearning for a liminal space, an abandoned past only alive in memory.

When asked about this phenomenon, Tiehexi simply said, “Well, it was inevitable.”

Tiehexi’s photographs occupy a similar niche online, attracting viewers who seek the safe harbor of childhood. A recent architecture graduate, Tiehexi has solo-traveled to over 200 cities, photographing more than 50,000 buildings in search of remnants of that bygone era.

His images spotlight pastel facades, geometric windows, and a design language that blends sharp, playful angles with soft, rounded features. There’s an art deco charm, but distinctively Eastern and local in execution. Arches, domes, and asymmetric towers appear in soft pinks, sandy browns, and light blues. These elements are rarely seen in today’s clean, functional urbanism. “Written on the teal-colored windows,” Tiehexi noted in one of his RedNote posts, “were our hopes and dreams of the future.”

A Feeling of Fire and Smoke

Beneath the geometric shapes and retro hues, Tiehexi’s photos carry a quiet melancholy. He admits he feels it, too, when shooting.

He grew up in Jilin, a province in Northeastern China known for its frigid winters and industrial legacy. “My childhood experienced 经济上行时期的美 (jīng jì shàng xíng shí qī de měi),” he said—a popular phrase echoed by countless nostalgia chasers online to describe Y2K, meaning “the beauty of economic growth.”

As a child, Tiehexi lived in a 筒子楼 (tǒng zǐ lóu), a type of communal apartment building where units line narrow corridors and neighbors often share bathrooms and kitchens. These once-common living spaces are disappearing, replaced by modern high rises. “The old towns are becoming more and more deserted as people move into city centers,” he observed, and documenting them is Tiehexi’s way of preserving their fading warmth.

But it’s not just architecture that draws his lens. “I used to go to RT-Mart a lot as a kid,” he recalled, referring to a popular supermarket chain. “I loved its interior design; it always had a vintage colorfulness. Even now, when I travel, I make a point to visit RT-Mart.”

He also photographs old malls and storefronts that have never been renovated, still clinging to their turn-of-the-century aesthetics. “There’s a lot of 烟火气 (yān huǒ qì),” he said, which literally translates to “The feeling of fire and smoke.” The phrase describes the vitality and warmth of everyday life. Perhaps that’s why Tiehexi’s photographs resonate so deeply. In today’s polished and monochrome cities, what we miss most is that fiery and smoky, messy and lived-in charm that defined Y2K neighborhoods.

Looking Ahead

Now, Tiehexi hopes to become a full-time artist and continue exploring that fading era through photography. He recently held a small exhibition and dreams of hosting solo shows and publishing a photo book in the near future.

When asked one final question—if a time machine could take him back to the 2000s, would he go?—he didn’t hesitate. “No,” he said. “Even though people lived well back then, the infrastructure just wasn’t as good. Today, everything is at your fingertips. Modern urban design has made life so much more convenient.”

That, perhaps, captures the essence of Chinese dreamcore altogether, not longing to return, but simply to remember.

All images courtesy of 铁合西街东.