Editor’s note: While the China-focused, Leipzig-based label Ran Rad might be the latest example of cultural exchange between Germany and China organized along the lines of underground culture, it’s far from the first. Below, Rolling Stone contributor Fabian Peltsch highlights some of the most important instances of cultural flux between each country’s shared passion for alternative music subcultures.

Goethe Institute China

Goethe Institute’s spacious digs in Beijing’s 798 art center

The Goethe Institute has played a leading role in Sino-German cultural exchange over the years. Opened in 1988 as language platorm, the Institute started organizing culture programs in China in 1993, a task that — especially in the beginning — was often more of a culture clash. “The Goethe Institute is somewhat different from other cultural institutes, like the Institut Français,” says Markus M Schneider, who curated the music portion of Goethe Institute Beijing’s 25th anniversary event in 2013, as well as a 10-hour overnight music program for its 30th anniversary event last October. “Their approach reflected the situation in post-war Germany,” Schneider adds. “Instead of presenting high culture from the archive, Goethe tried to create new spaces where culture could actually happen. In that sense, it became a shelter for many Chinese creatives, who would not have been able to gather with like-minded people or present their work and thoughts elsewhere.”

“[Goethe Institute] became a shelter for many Chinese creatives, who would not have been able to gather with like-minded people or present their work and thoughts elsewhere.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BqcVyQIlcqf/

One of Goethe’s biggest endeavors was the three-year traveling event “Germany and China – Together in Motion,” which was supposed to strengthen the image of Germany as a “future-oriented country.” Besides showcasing big businesses, the Instutute held concerts with more than 100 German bands in parks and public spaces in cities including Nanjing, Chongqing and Wuhan, mostly supported by Chinese counterparts. “Normally, a Chinese rock band would never have the chance to play in front of 50,000 people”, says Yu Xiao, former head of Goethe Institute China’s Culture Department. “Most of Goethe’s events are free — that’s why they can have a much stronger impact than the average underground space.”

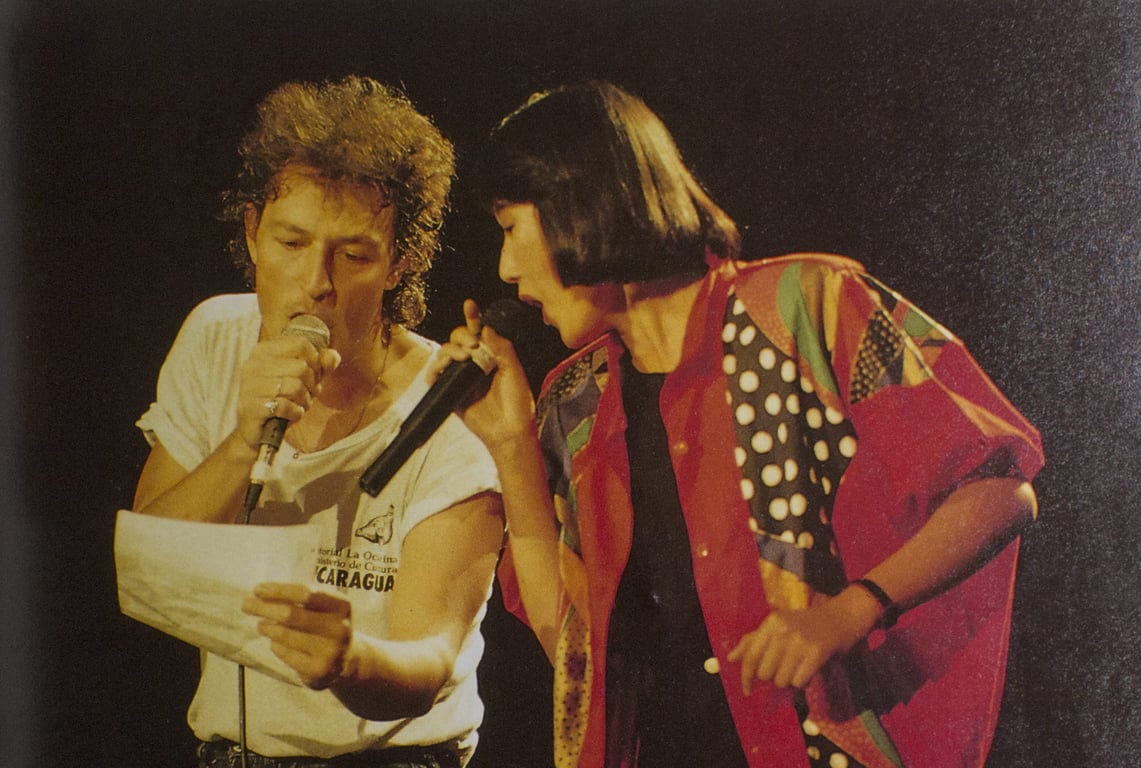

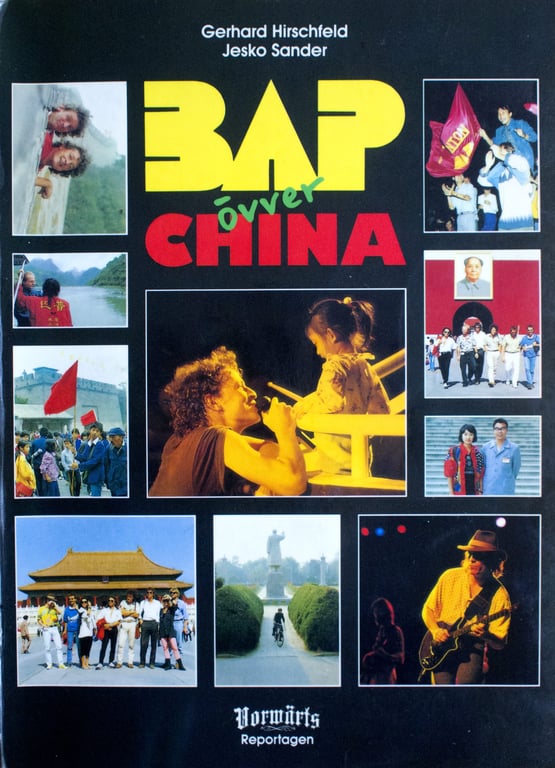

BAP övver China, 1987

One of the first Western groups that was allowed to play in China during the ’80s reform era was BAP, a pop-rock band from Cologne with eleven albums reaching the top of the German charts to this day. Organized by the Society for Sino-German Friendship, BAP played three shows in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou in 1987. Security guards in large numbers were a constant presence. The Communist Party was about to hold its 13th National Congress, which would determine whether the country could continue the policy of opening up launched less than a decade earlier. The visit by BAP, who were hailed on hand-painted posters as “Modern Western Music,” soon turned out to be a handshake fest, dinners with politicians and factory visits included.

At their first show in Beijing, BAP played in front of 18,000 people. The pacifist band, which was part of a major 1983 charity show positioned against the deployment of American nuclear missiles in Central Europe, divided their set into three socially-conscious blocks: “love Songs,” “political Songs,” and “songs about the problems of the European youth.” Accompanied by two female background singers, dressed up in the latest fashion with spandex suits and sporty headbands, BAP might have proven for China’s political elite that Western influences don’t necessarily need to cause an uproar, like Wham! did during their CHina appearance two years earlier.

China-Avantgarde Festival, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 1993

“In 1993, Chinese rock ‘n’ roll was considered world music,” says Udo Hoffmann, who that year organized the first Chinese underground music festival outside of China. Hoffmann’s China-Avantgarde art and music exchange in Berlin’s House of World Cultures was planned under the radar of the Chinese government. Hoffmann — who is fluent in Mandarin, had worked as a lector and teacher in Beijing, and had already organized the first jazz festival in China that same year — managed to fly out soon-to-be legends like Cui Jian, Tang Dynasty, electronic music pioneer Wang Yong, and the all-female rock band Cobra.

Related:

WATCH: Stories Behind Dakou, China’s Semi-Illegal ’90s Music ImportsArticle Nov 15, 2017

WATCH: Stories Behind Dakou, China’s Semi-Illegal ’90s Music ImportsArticle Nov 15, 2017

It was an eye-opening experience for everyone involved. Members of Cobra were hammered by the German press about a possible feminist background. Hoffmann almost got evicted by the authorities. “The Chinese Ministry of Culture felt omitted… They wanted to determine who represents the country abroad,” he recalled in a 2003 interview. In the end, the officials welcomed the event’s surprising soft power, and Hofmann went on organizing big concerts with his own event company. His later endeavors included the Heineken Beat 99 festival in Beijing’s Ritan Park, which would become a benchmark for music festivals in China.

Beijing Bubbles, 2006

In 2004, Berlin filmmakers Susanne Messmer and George Lindt traveled through China as backpackers. After meeting members of the all-woman punk band Hang On The Box, they decided to shoot a “guerilla-like” documentary about Beijing’s musical underground, portraying bands like Joyside, New Pants, and Mongolian fusion rockers T9 (later known as Hanggai). Beijing Bubbles was released in 2006 in Austrian and German cinemas, and at film festivals around the globe. As one of the first English-subtitled documentaries on China’s rock scene, it shaped the image of China as a subversive island where “punk hasn’t degenerated into a fashion statement,” as Lindt pointed out in a trailer, but where individualists like Joyside singer Bian Yuan are suppressed by an authoritarian state.

Listen to Joyside and Hang on the Box:

Five Completely Non-Traditional Love Songs for Chinese Valentine’sArticle Aug 28, 2017

Five Completely Non-Traditional Love Songs for Chinese Valentine’sArticle Aug 28, 2017

The filmmakers also distributed the band’s albums via their own label, Fly Fast Records, advertising Joyside as a “thorn in the flesh of the government.” The media buzz around Beijing Bubbles led not only to a 2007 Germany tour for Joyside, but also to the odd yet almost forgotten compilation Poptastic Conversations China, on which some of the biggest German bands of the time, like Die Ärzte, sang their songs in crash-course Mandarin while Chinese indie bands like Carsick Cars tried their best to not ruin their own songs in German.

Tresor (Almost) Comes to Beijing, 2010

Tresor pops up at Beijing’s INTRO festival, 2010

Media hype during the 2008 Olympics sparked the idea that China’s underground might be the next big thing. Tresor Club, one of the most important breeding grounds for Berlin techno and a symbol of the re-unification of the youth in East and West Berlin, wanted to be there when it happened, and that year announced a forthcoming Beijing branch. A steady flow of German DJs was supposed to host residencies from 2010 on, while Chinese artists were supposed to come to Berlin on a regular basis in exchange. The preparation, supported by Goethe Institute and the German Ministry for Foreign Affairs, took two years. The location — a bunker underneath inner Beijing alley Fangjia hutong — was furnished, the website ready.

Related:

Yin: Gripping Techno Thriller from Beijing Producer ShaoArticle Oct 25, 2018

Yin: Gripping Techno Thriller from Beijing Producer ShaoArticle Oct 25, 2018

But then — nothing happened. Tresor founder Dimitri Hegemann later explained that tensions surrounding China’s subculture after the 2011 arrest of artist Ai Weiwei (who is almost as famous as David Hasselhoff in Germany), as well as a flood that inundated the proposed Tresor Beijing site, terminated the project. A person involved with organzing Tresor’s aborted Beijing output claims that it never materialized due to organizational and financial differences. Some of the organizers still managed to build a corridor between Berlin and Beijing nightlife, however. Mumu Wang and Markus M Schneider, who were involved with the project, went on to found Metrowaves in 2011, a fruitful electronic music encounter between artists from both countries. In the long run, the connection to the Tresor family also helped Beijing producer Shao score a record deal with the club-owned label in 2015, making him the first Chinese artist to ever release there.

Besides long-term expats like Schneider, who has curated several festivals and conferences in China over the last ten years, or Philipp Grefer, who has invited 21 German artists to China since 2007 under his Fake Music Media label, there have been a few other German artists who’ve bonded more deeply with China than just for the average tour.

Blixa Bargeld

Blixa Bargeld, founder of industrial pioneers Einstürzende Neubauten, made Beijing his home between 2007 and 2008, while his wife, the Chinese mathematician Erin Zhu, built up a company. He was frequently quoted as saying that the vital pre-Olympic Beijing reminded him a lot of Berlin in the 1980s, especially “in terms of attitude,” as he’d later tell The Beijinger.

Blixa, himself a legendary, key figure in the roaring underground of the then -divided German capital, dove into Beijing’s art and music scene during his time there, led along by his old friend, the musician and music critic Yan Jun.

Related:

Radio Enemy: Experimental Musician Yan Jun Digs Into His Dakou CollectionArticle Apr 05, 2018

Radio Enemy: Experimental Musician Yan Jun Digs Into His Dakou CollectionArticle Apr 05, 2018

In 2007, Blixa produced the self titled-debut album for White, the experimental project of Carsick Cars founder Zhang Shouwang and Hang on the Box drummer Shenggy Shen. German influence on the album can be heard not only in the “Berlin School” synth-scapes and hints of minimal techno, but also in the name of the opening track, a slogan borrowed from Chinese furniture company Baiqiang: “Zhende hen deguo,” or “Really real German.” White also supported Einstürzende Neubauten on their Alles Wieder Offen Tour in 2008.

Blixa also returned to Beijing on several occasions, includingin 2013 for a Goethe Institute-backed theater performance entitled Executing Precious Memories, which included Snapline’s Li Qing and guitarist Li Jianhong as performers.

Mark Reeder

Mark Reeder has always had his finger on the subcultural pulse. In the early ’80s, the Manchester native moved to Berlin, where he soon became an important part of the scene, managing bands like Malaria! and organizing the first (illegal) punk shows in the Sowjet east (check out his amazing documentary, B-Movie, for more on this).

While in Chengdu to perform at the 2017 Morning House Festival, Reeder’s old friend Ni Bing of Drum Rider Records introduced him to local band Stolen. After witnessing their performance, Reeder confessed that he hadn’t been that excited since he’d first seen Joy Division. “It was one of those revelationary moments you don’t get very often,” he said to me afterwards.

Related:

Chengdu’s Stolen Refresh the Post-Punk-to-Techno Vector with New Album, “Fragment”Article Nov 05, 2018

Chengdu’s Stolen Refresh the Post-Punk-to-Techno Vector with New Album, “Fragment”Article Nov 05, 2018

Reeder ended up produced Stolen’s 2018 album Fragments, and revived his MFS label to release it. The album is a mix of electronic rock and techno that Reeder refers to as “the new Sinographic sound of young China.” The 60-year-old, who also produced Hang on the Box’s 2017 album Oracles, says that he wants to break stereotypes that Germans still hold about underground music from a Communist country. “Having had the opportunity to experience what it was like in the GDR and other Soviet satellite states, I can still see one or two Communist-era similarities in China, but in reality, the only major similarity is that the authorities still want bands to submit their lyrics,” he tells me. “In East Germany, the moment you formed a band you were under the scrutiny of the secret state police.”

—

Cover photo: BAP singer Wolfgang Niedecken on stage with chinese Pop star Cheng Fangyuan (from BAP övver China, published by Vorwärts Verlag GmbH, Bonn 1989)

You might also like:

Someone Needs to Tell Dietfurt Bavaria They “Can’t Celebrate” Chinese New YearA small town in Bavaria goes all out for Chinese New Year, with parades, qipaos, an “emperor” and lots more – is it cultural appropriation?Article Feb 08, 2019

Someone Needs to Tell Dietfurt Bavaria They “Can’t Celebrate” Chinese New YearA small town in Bavaria goes all out for Chinese New Year, with parades, qipaos, an “emperor” and lots more – is it cultural appropriation?Article Feb 08, 2019

Yin: Symbiz Brings Cantonese Bass Music from Germany to Uganda in “Faai Di” Music VideoArticle Aug 11, 2017

Yin: Symbiz Brings Cantonese Bass Music from Germany to Uganda in “Faai Di” Music VideoArticle Aug 11, 2017