It’s said that a rising tide lifts all boats, and New York-based 88rising has undoubtedly done more than any other organization to raise the profile of Chinese hip hop on the global scene. “It’s hard to do what we’re doing… there’s levels to this,” founder Sean Miyashiro told me last month in Shanghai, days after touching down in China for the first time. “This is no joke, this is charting in the US. Especially because we’re independent, we don’t have a big machine behind us. So, nah… there’s nobody in the world doing what we’re doing.”

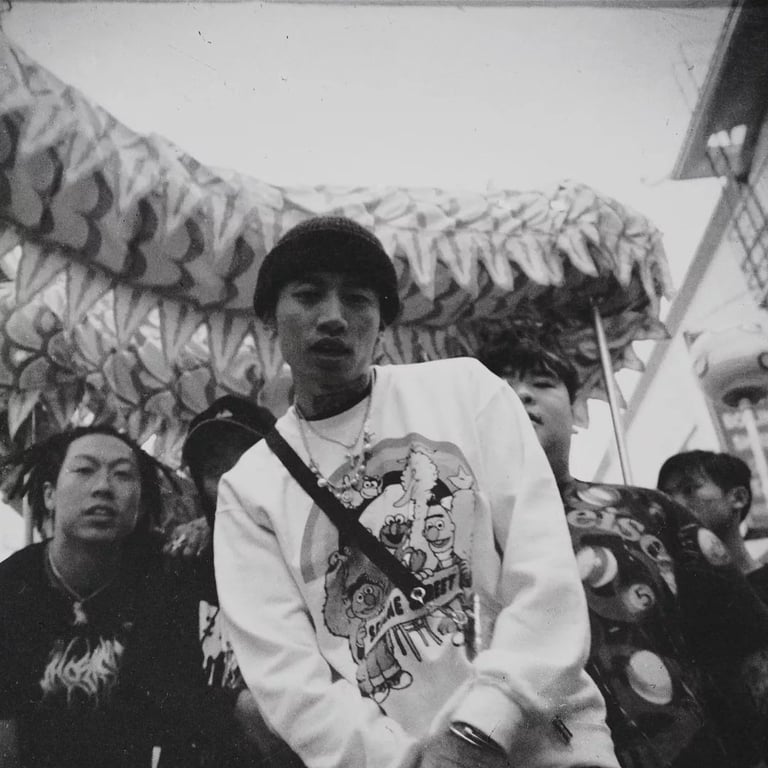

Though he comes off as overly hyperbolic — “Forget about Chinese hip hop history, forget about Chinese music history — it’s straight up Asian music history,” Miyashiro later says of Higher Brothers’ just-released sophomore album Five Stars — it’s hard to argue with the list of milestones that the Chengdu rap crew has achieved over the last year under 88’s banner.

Higher Brothers completed two US tours in 2018 — one supporting Indonesian rapper Rich Brian, 88rising’s biggest star, and one on their own as headliners — where they played in front of sold-out crowds on both coasts. Higher Brothers also turned heads at 88rising’s inaugural Head in the Clouds festival in LA last September, and were singled out for their “kinetic” presence in Pitchfork‘s review of an otherwise middling group album of the same name co-starring labelmates Brian, Keith Ape and Joji. Early fan reactions to Five Stars are also favorable, despite the language barrier — one Redditor claims to have a harder time understanding Soulja Boy’s guest spot on mid-album track “Top” than any of the Bros’ transitions between English, Mandarin and Sichuanese.

Related:

Higher Brothers Drop New Video, Announce February Release of 2nd Album “Five Stars”The Chengdu rappers return with a new track ahead of the February release of their long-awaited full-length followup to 2017’s Black CabArticle Jan 15, 2019

Higher Brothers Drop New Video, Announce February Release of 2nd Album “Five Stars”The Chengdu rappers return with a new track ahead of the February release of their long-awaited full-length followup to 2017’s Black CabArticle Jan 15, 2019

Much of 88rising’s success in translating the Higher Brothers hype is due to the fact that it operates more as a PR agency than a record label. Miyashiro estimates that 30% of the company’s staff is dedicated full-time to music — this includes marketing, A&R, creative, and artist management. The other 70% is split between video production, business development (maintaining relationships with brands like Sprite, Adidas, and Beats looking to tap 88rising’s consumer base), and fostering direct relationships with streaming music and video platforms, the digital milieu for which 88rising tailors most of its output.

Rather than working within entrenched music industry networks, 88rising has built its clout largely through canny use of social media, producing viral hits like “Rappers React to Higher Brothers” in-house and developing personal relationships with platforms such as YouTube, Apple Music, and Spotify to augment the algorithmic performance of its content. “These platforms are truly global, and we have direct relationships, like with the Southeast Asia Spotify team and Apple Japan,” Miyashiro says. China presents a unique challenge, however, with most Western streaming platforms blocked and replaced by local equivalents.

This explains why 88rising’s only office outside of New York is in Shanghai, where the company employs more than a dozen full-time staff. It also hints at why Miyashiro made his first-ever trip to China last month: 88rising won Chinese music streaming platform NetEase’s label of the year award in January, with Higher Brothers taking the award for hip hop artist of the year at the same event. (Ironically, one month after receiving these awards, several 88rising tracks — including “Swimming Pool” and “Red Rubies” from last year’s Head in the Clouds album — were pulled from NetEase, ostensibly for lyrical content falling outside the comfort zone of Chinese censors.)

Despite a nearly universally positive reception in the US — see glowing profiles in the New Yorker, Rolling Stone, and Bloomberg for proof — 88rising also has its detractors, especially among people with knowledge of both sides of the US/China cultural divide. Rapper Bohan Phoenix was instrumental in managing 88’s relationship with Higher Brothers early on, and acknowledges that the brand has “single-handedly helped raise the profile of Asian creatives in the last couple of years,” but questions 88rising’s myopic promotion of hype over a sustained engagement with the community of artists it claims to represent. “Through marketing, through PR, through millions of dollars of investment, they have gone from zero to capturing the attention of the world as the first and only platform to really ‘curate’ Asian artists exclusively,” Bohan says, before adding:

“Being there since day one of the company, and having helped them sign and manage Higher Brothers, as well as help with their day-to-day between New York and China, I’ve seen firsthand that they are more of a PR and advertising company than a music company. Their four top artists — Higher Brothers, Rich Brian, Keith Ape and Joji — were all already popping before 88 came along and scooped them up. With Higher Brothers, who were already doing good in China, they really saw the ‘Asian Migos’ image and decided to push that fully without thinking about the consequences. Rich Brian was an amazing and talented comedian, but then a joke song blows up, and he decides to take this joke and run with it and make a real career out of it… Keith blew up on his own off of ‘It G Ma.’ Once 88 milked his popularity, they just forgot about him and moved on to Brian, and it’s safe to say that Keith’s career has been fizzling out. And of course Joji was already big as Filthy Frank and Pink Guy, and he already had a built-in following.

“If 88 truly cared about cultivating Asian talent and culture, they would be covering and highlighting loads and loads more artists, but because they aren’t as marketable, or don’t have a big following, they are completely left in the shade and neglected by 88… Just because 88rising happens to be the first platform to focus on Asian culture, does not necessarily mean it cares about the well-being of the community.”

Related:

Bohan Phoenix Injects a Dose of Reality into China’s Hip Hop Boom on New Track “YMF”“Chinese hip hop is a misleading title to me,” says the bilingual rapper trying to flip the table on dubious labelsArticle Jan 28, 2019

Bohan Phoenix Injects a Dose of Reality into China’s Hip Hop Boom on New Track “YMF”“Chinese hip hop is a misleading title to me,” says the bilingual rapper trying to flip the table on dubious labelsArticle Jan 28, 2019

Regardless, it’s clear that Higher Brothers still has the full backing of the label. Five Stars may or may not prove the “pivotal moment in Asian music history” that Miyashiro claims it to be, but the promotional scale behind it is undeniably epic: the Bros are gearing up for a 27-city world tour, where they’ll hit new markets like Detroit, Dallas, Barcelona and Berlin in addition to their proven coastal strongholds of New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. In LA Higher Brothers is playing the storied, 1,100-capacity Regent Theatre — they’re maybe the only underground Chinese act with the potential to sell out a room that big.

Can exaggerated PR copy (“Higher Brothers are defining what it means to be Chinese in an increasingly globalized, internet-fueled world,” runs the Five Stars press release) and a fixation on digital metrics (“over 250M streams globally,” it states later) translate to a sustainable model for artist development? Are YouTube views and Spotify playlist placements just the way the music industry works now, and the only path forward for other Chinese artists hoping to travel the path blazed by Higher Brothers? These are the questions hanging over how much further 88 can rise, and what future claim Chinese music might hold on the global attention span.