Artist, writer, and curator Julian Junyuan Feng’s Instagram handle is philipglasswasataxidriver, a sobriquet that’s memorable enough that I’ve heard people use it to refer to him offline. After all, it’s a factually accurate reminder that even artists need a reliable way to pay the rent. If that was already the case for a major minimalist composer in the much-mythologized ungentrified New York of the 1970s, it applies even more now. Artists in any medium not only need to create work and worry about financial stability, but also constantly serve as their own advocates and promoters (hence the Instagram account).

It’s a delicate balance, one that Feng (who was born in Sichuan province in 1991) is navigating from Zhuhai in Guangdong province, having recently relocated from Shanghai to take a position as a senior lecturer in film and new media at BNU-HKBU International College. While Feng began his artistic career creating essays films that traced out hidden linkages between technology, Cold War intrigue, and facets of online pop culture, he’s since moved into producing physical objects (sculptures, prints of computer-generated imagery, and more) that explore similar themes — and occasionally imply an interest in medieval armor.

RADII caught with Feng over email to learn more about his practice, touching upon work-life (and art) balance, granular synthesis, and nostalgia for 90s globalism along the way.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Simon Frank: Since a lot of your work is computer-generated, I wanted to ask what your work process is like? Do you go from ideation and research directly into animation/imaging programs? Is there a stage of sketching or experimentation with raw materials?

Julian Junyuan Feng: Yes, there indeed exists a stage of sketching and noodling around in software with whatever raw material I can find. It’s funny that I completely lack the basic training of drawing, which means I usually can only do the very important pre-visualization stage in the 3D production software I use, and am limited and guide-railed by the specificities of the software. Needless to say, there’s often a huge gap between ideation/research and the final outcome, in a good or bad way, depending on the models, plugins, workflows, and tricks that I stumble upon. In the same vein, a lot of my ideas couldn’t come into fruition in a visual form, for the lack of certain know-how and realistic low-budget, one-person-crew solutions. I personally feel that everything after the ideation and research stage manifests itself as an engineering problem. Sometimes I enjoy solving them, but most often I don’t. It’s a pity that our ideas are almost infinitely malleable, but our material world is not.

Simon: As I understand, you started out making essay films, but recently have been working a bit with sculpture. What fuelled this exploration? Do you think it’s something you’ll continue?

Julian: In hindsight, making essay films seemed a natural inclination after being trained in art grad schools. When I look at practitioners a bit younger than me, I see a similar tendency. Art schools, at least the ones I went to, put a lot of emphasis on producing discursive works. Essay film in general is a budget-friendly way to put out discourses and the genre itself welcomes polemics and combativeness, which can be very desirable for young artists. Also, the production procedures can be fairly repeatable and integrated into something like an assembly line, with found footage, archival materials, voice-overs, a little bit of visual effects, so on and so forth. I stopped making essay films because I saw the segment of young moving-image artists in China became saturated with essay film aficionados, and the whole thing felt a little bit formulaic after just a few years. I started to make sculptures because it was the medium that I had zero training in and was most curious about. Although making sculptures always entails inevitable overheads — extra money, resources and logistic efforts — I still enjoy it and will continue to do so.

Simon: It seems that much of your work examines issues people all over the world encounter as “global citizens” — global warming, macro-systems, encounters with non-places. What draws you to these topics, and what do you think is illuminating about observing them from China?

Julian: The appearance of “global” issues in my works may only be a side effect of something else. I don’t think I’m pursuing “globalness” per se when choosing topics to explore — even the word “global citizen” feels a little bit nostalgic these days […] I’m interested in something that literary scholar Emily Apter once dubbed “one-worlded-ness,” or, some others may call “all-connected-ness.” It is a specific paranoiac epistemology inherited from the Cold War and is still very much alive today, a view that spurs conspiracy theories and is hostile to forms of exchanges, be it cultural, material or bodily. Although extremely “weird,” this paranoiac world view also holds a certain degree of truth in it. Remember the often-quoted Frederic Jameson line, conspiracy theories are “poor man’s cognitive mapping.” We are deprived of the right to know in the modern world, either because of the power institutions designed to keep us in the dark, or because the world system simply grew too big and too complex for a human mind to grasp. Sometimes the only walking stick left is our own imaginations, and in that case, it doesn’t matter anymore if the “knowledge” we get by reasoning through imaginary connections are factually sound or not.

Recently I was teaching a course on the history of computer graphics and my students were shocked to find out the military origin of their beloved 3D games and cute avatars. It all started from a research grant that the University of Utah got from the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). To give another example, not long ago I learned that the Black Panther members who were part of the delegation to Maoist China in the early 70s brought back a special ear acupuncture technique in order to detox their community and curb the ongoing heroin crisis. This was a vivid case of people’s medicine and South-South alliance. The undercurrents veiled by mainstream historiography might in fact be the most inspiring.

Speaking of the piece I did about Gorbachev’s forehead, although Gorbachev stepped down as the Soviet Union’s supreme leader two weeks before I was born in 1991, I still have vivid childhood memories of his TV clips, with his telegenic disposition and his sprawling, archipelago-like birthmarks. A few years ago I learned about the myriad of jests and conspiracy theories about his birthmarks. Even mischievous postmodern novelists like Don DeLillo poked fun at them. I can totally relate to these bizarre, slapstick, somewhat low-brow infatuations and in fact they were just stand-ins for a repressed curiosity about the deeper structure of the human world. These stranger-than-fiction, mind-bending connections, when properly historicized, become uniquely revealing. So, to answer the question, the “globalness” in my work is just a façade, and deep at work is the boundary-breaking and deterritorialization effect inherent to these weird connections.

Simon: Do you think being in Shanghai gives one a different perspective as opposed to other cities in China? In that regard, how do you think your relocation to Zhuhai might influence your work?

Julian: To be perfectly honest, I moved to Zhuhai for a teaching position, which I very much needed due to a sluggish economy and the financial difficulties I experienced as a freelancer in Shanghai. I still much prefer living in Shanghai over other Chinese cities. However, maybe moving a bit away from the often cacophonic Shanghai art scene is good for my well-being and concentration.

Simon: What advantages does China offer young artists? What are some difficulties you face?

Julian: The biggest difficulty I encounter is that it is really hard to see good and inspiring art in China. Not saying that art here is all trash, but I often see more repetition and derivatives, and the range of topics are always limited. Another downside is that the market here plays too big of a role in the ecosystem of art — which may be true everywhere — but because of the severe lack of institutional and academic players in Chinese contemporary art, the issue becomes extremely pressing. Speaking of advantages, if any, I would say it’s the relatively low production and living costs, when compared to places usually perceived as art capitals.

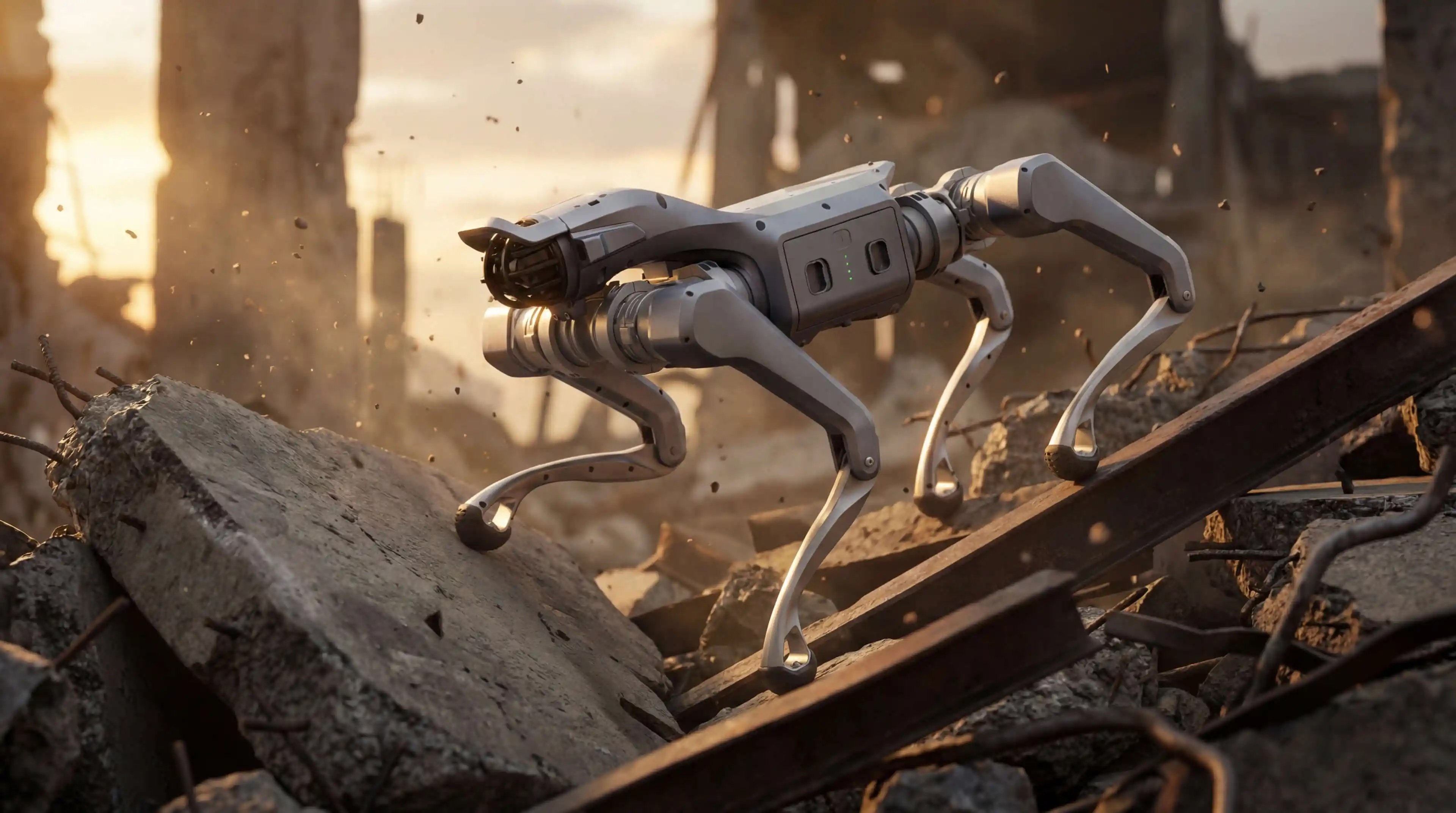

Simon: Though your work deals with some fairly heavy themes, I feel there’s also an element of humor involved in pieces like Lil Gorby, the Marked One (2023), or Minerva’s Drone Crashes at Dusk (2023), even the Pinocchio-like figure in Der Bau (2023). Do you think about humor while creating work? Why is it important to you, or not?

Julian: I think I am a fairly funny person, but also generally pessimistic about the state of affairs, politically or economically. One can dissect cynicism as either funny pessimism or pessimistic funniness. I don’t think cynicism is necessarily a bad thing, especially in a cruel world which we can do very little about. Cynicism can be productive and an art of its own, not in the sense that it produces anything concretely, but that it can be uniquely revealing. Oftentimes, I find topics that I am very interested in, for example, an episode in the Japanese leftist movement, or some weird technical object from the Cold War era, but I struggle to find a funny enough angle to tackle it. For me the humor and funniness is the magic sauce of a good artwork, something that helps to differentiate it from a piece of academic writing or a hodgepodge of notes and sketches. A lot of research-based biennale art today feels pedantic and derivative for presenting its research “as is” and lacking affects of sensible intensity. Over the years I never quite managed to infuse my work with a strong affect like awe, disgust, or grief, which I really really wanted to do. A sense of humor ends up being the least I can do. I would say it is still suboptimal, but that’s how cynics see things anyway.

Simon: Finally, I know you went through a modular synth/music hardware phase. Have you made soundtracks for any of your video pieces? Knowing that you recently gave a lecture related to Detroit techno, what interested you about this technology or means of producing music?

Julian: I’ve made some very simple soundtracks for my videos using basic audio stretching, pitch shift, beats slicing, and sometimes granular synthesis. Unfortunately I had very little training in music theory and instruments. I wish I could compose and assemble a good soundtrack in the future. My previous enthusiasm about synthesizers and music hardware was part of my general interest in mechanism and apparatus. When entering a new field of inquiry or hobby, the impulse to learn and acquire hardware usually feels the strongest, which was also true when I learned about photography, film, or CGI. More often than not my craze on hardware and technology becomes counterproductive and distracting. I am still extremely interested in the history of electronic music and beat-making as a form of resistance, but I don’t think I can proceed any further in proper music-making due to limited time and energy.

Banner image: Minerva’s Drone Crashes at Dusk, 2023, CGI, archival inkjet print, 40 x 40 cm. Courtesy the artist.