Though often portrayed in Western media as a monolithic, atheistic monoculture, China has one of the most complex histories of religion and spirituality among the world’s civilizations. Understanding the histories, myths, and enduring spiritual and pop-cultural appeal of China’s long list of deities is essential to understanding the country as it exists today, says Xueting Christine Ni, who has a book on the subject out on Friday (June 1).

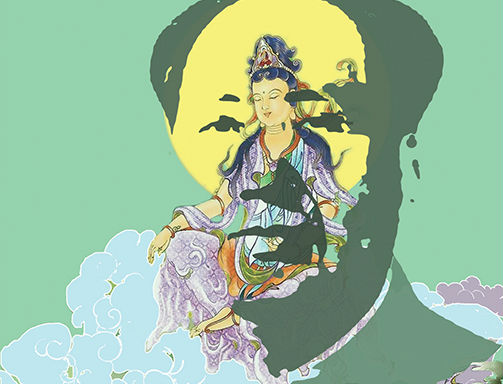

Ni, also somewhat of an authority on Chinese pop culture (she wrote about ghosts and ghouls for us around Halloween), has put together a “shortlist” of 60 beings — gods and goddesses, along with “spirits, immortals, heroes, elementals, sages, guardians and so forth” — showing the connective tissue of deep-seated spirituality connecting figures From Kuan Yin to Chairman Mao, as the book’s title has it, to Chinese society and culture.

Ahead of the book’s release, RADII caught up with Ni for a dive into China’s complex canon of mytho-historical legends, and to hear why she thinks getting a handle on them can help anyone hoping to understand the country’s role in the world today.

Xueting Christine Ni

RADII: Let’s start off with a basic question: what does “deity” mean in the Chinese tradition? Your book covers a wide range of what people in the West might call gods or goddesses, immortals, folk heroes… How is this type of being in Chinese myth or history different from the Western conception of gods, such as the Greek pantheon, or other contemporary polytheistic traditions, such as Hinduism?

Xueting Christine Ni: The Chinese concept of gods fundamentally differs from a lot of Western cultures. It’s a big mix of traditional-type all-powerful spirits, embodiments of virtues, all the way down to real-life heroes who get referred to as gods in a similar way as the canonizing of saints. Very often, officially anointed deities don’t even live within just one canon, or religion. They have entirely separate lives in popular religion and folklore.

You see, China has been seen in the West as this great monoculture. That’s not entirely the West’s fault, because China has always tried to present this great united front to the outside world, but actually it’s a whole network of different peoples, and faiths — with there being maybe three big ones — which have not only coexisted for centuries, but intertwined with and enhanced each other.

[pull_quote id=”1″]

Buddhism, which was not even from China to begin with, has developed unique branches there, with distinct Chinese god identities. Confucianism is treated like a religion, but it’s more of a way of governance, a code of behavior, than a belief, whilst Daoism, which is the largest of China’s natural belief systems, is all about the state of existence itself. That’s all on top of the complex collection of folk religion, which takes whatever it wants, wherever, and weaves it all together, spawning new gods when new troubles or technologies emerge.

To complicate things even further, the boundaries between these four morph and merge. Part of why I wrote this book was to help my readers start to make sense of China’s chaotic spiritual life. I think understanding how these belief systems have vied, compromised and settled is a very important insight into the Chinese Psyche as a whole.

[pull_quote id=”2″]

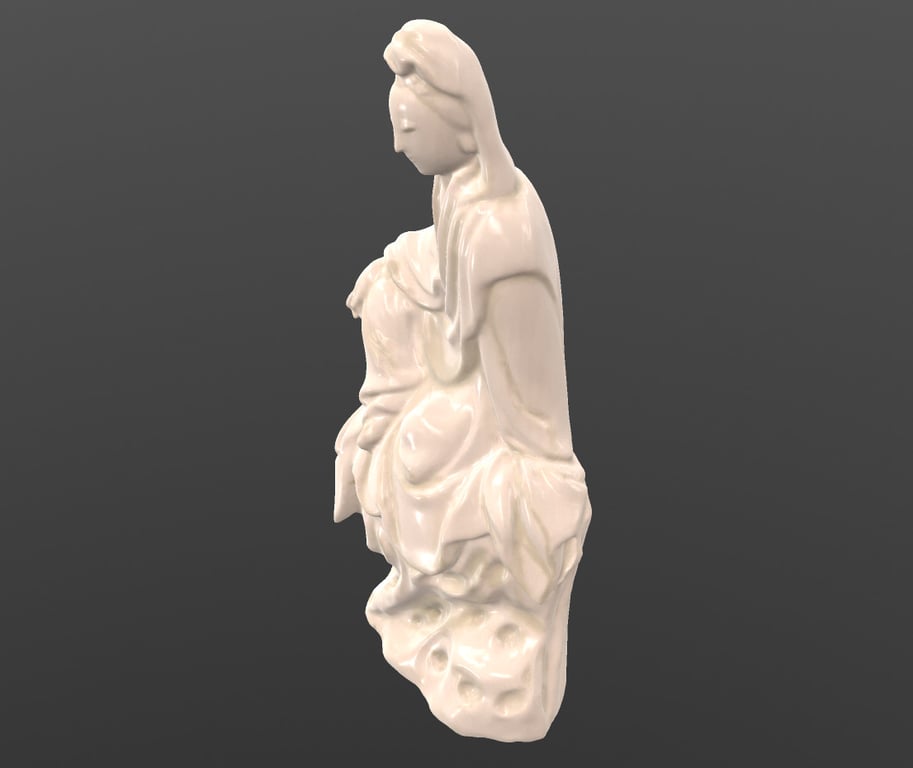

One of the beings you feature in the book, perhaps the best known in the West, is Guan Yin, the goddess of mercy and compassion. This is a female deity that is also worshipped as the male bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara in Indian Buddhist traditions. What do you think is particularly “Chinese” about Guan Yin, the way this deity is depicted or worshipped in China vs India (or elsewhere in Southeast/East Asia, where the same god is worshipped under different names)?

Absolutely, Guan Yin was among the first deities I selected when I was making my shortlist for this book — yes, 60 deities in Chinese religion is a shortlist. The reason why my US publishers wanted to have her name in the title, and retain that peculiar “Kuan Yin” variation of spelling in the text, is precisely because she has such a phenomenal following under that name in the States, but actually, she’s well known all through the West.

Guan Yin is in fact the Chinese translation of Avalokiteśvara, a shortened form of Guan Shi Yin, meaning “hearer of the world’s cries.” However, the Guan Yin we think of today is very different from her origins. Introduced into China around the time of the Three Kingdoms [220-280 CE], she’s developed a separate Chinese identity over several hundreds of years, as a sort of ambassador between the Chinese people and Amida Buddha.

One immediate clue is in the fact we refer to the deity as a “she” and a goddess. Bodhisattvas are meant to be asexual, but early Chinese versions were mainly male to begin with, and then became female during the Tang Dynasty [618–907 CE], which corresponded to an increase of female Buddhists, and legends surrounding women in the nobility taking on the faith, such as story of the death and resurrection of the devout Princess Miao Yin.

Left: He Xian Gu; Right: Hsien-Ko (Lei Lei)

One theme that you follow closely is how Chinese deities are being used today in a variety of popular media, such as TV, movies, and video games. Can you share one or two examples of this phenomenon that you’ve found the most interesting?

Chinese deities have never really been far from the popular imagination, and if any of your readers are gamers, they will have heard about the Monkey King and Guan Yu, even if they are otherwise unfamiliar with China. The stories of these two are so engaging that each generation can find their own take on them. One I found quite interesting is an adaptation of He Xian Gu, Celestial Healer and one of the Eight Immortals, who we see appearing as the Chinese zombie Lei Lei in Capcom’s classic ’90s arcade game Darkstalkers. This is a representation that has taken only a hint of her herbalist origins, and married it to the popularity of Chinese jiangshi [僵尸; zombie] films at the time, by putting her in a revamped, sexy version of a Qing Dynasty official’s uniform.

Modern-day Zhong Kui

Another interesting one is Zhong Kui, China’s most famous demon slayer. As a demon slayer who is a ghost himself, the deity’s remarkable origins really lend themselves to versatile reinterpretations. Hong Kong cinema channelled the deity’s corrective and exorcist power into that of a modern day cop, killed on duty and revived, unleashed to the world in a sort of half-Robocop, half-Frankenstein being that has to find his killers and help his wife deliver the baby.

Recently, the Light Chaser Animation studio has produced a reinterpretation of the Men Shen, or door gods, released in the West as The Guardian Brothers and voiced by a Hollywood cast. The film portrays the gods as unemployed celestials fighting to retain their role as gods in a world that’s losing its belief in them. It’s a charming story, though I don’t think this fate is anything for the door gods to worry about in China.

How did some of these same figures circulate in the ancient equivalent of pop culture? Did you find any interesting cases of deities permeating song, dance, poetry, etc in earlier dynasties?

I have chosen to write about deities that had, and still have, major significance to people. A lot of my research on the origins and history of these gods led me to classics of mythology, such as the Classic of Mountains and Seas, Gan Bao’s In Search of the Supernatural, and historical texts such as Huai Nan Zi and Sima Qian’s Historical Records. However, a considerable amount of information on the evolution of the deities would inevitably come from poetry, theatre, and popular fiction, because those are the mediums through which veneration for the deities would manifest, if they are popular.

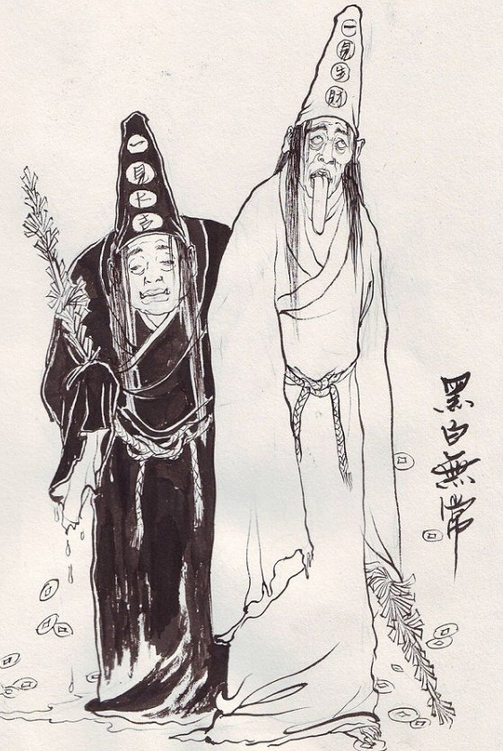

For instance, we know that many great Tang poets were inspired by Lu Yu, the Tea Sage, because they wrote about him in their poetry. Various legends of White Snake and Yuan Dynasty plays show us how the characteristics and appearance of Shou Xing, the god of longevity, have developed in the popular consciousness. The Hei Bai Wu Chang, minor gods in the Daoist canon, achieved their status in Chinese pop culture by being transformed into badass hunters of stray souls in urban legends. Part of their story would be told in the pages of works such as Li Qingchen’s Zui Cha Guai Shi, or Strange Tales of Drunken Reverie. In fact, there’s a whole tradition in China of the Chuanqi genre, a gathering of tales of the strange that have proved very useful when looking at deities who’ve risen out of folklore.

Hei Bai Wu Chang (黑白无常)

[pull_quote id=”3″]

You note in the intro to your book that China’s three major spiritual and philosophical traditions — Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism — overlap in many ways, but that Confucianism, which is more of a belief system guiding civil and social life than a “religion” as traditionally defined, is less concerned with the creation of gods. That said, what Confucian figures do you feature in the book?

I write about a few notable thinkers who created new branches based on their schools of thought, such as the Neo-Confucians Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming, who created Xin Xue, or Cultivation of the Heart. But few Confucian thinkers came close to achieving the god-like status of Confucius himself, whose veneration started off as an ancestral cult after his death, and which over a couple of centuries became nationwide in all schools, by imperial decree.

The Chinese are a civilization that have always placed great emphasis on scholarly excellence in whatever field. They have incredible reverence for wisdom and learning, so in a way it’s perfectly natural for the sages among them — not just Confucius, but the Tea sage Lu Yu, and Mei Ge, who are credited with inventing cloth dying — to be worshipped like gods, and to have the word sheng [圣; sage] in their titles.

On the same note, you mention Mao Zedong in the book’s title. In what ways do you think he has been mythologized or deified?

Mao Zedong was a combination of many things. He was a very charismatic person, a great scholar, exceptionally adept at his use of language, and, of course, he was photogenic and very paintable. His Analects — aka the little red book — is a much better read than a dry party manifesto. All of these attributes made him very easy to venerate. If you add to the mix a nation with a spiritual void, just pulled out of prolonged, severe trauma by this very savior, a country full of fired-up hormonal teenage red guards, it’s the perfect recipe for godlike worship. Mao still has a considerable following in China today, which can be seen in how his image is presented in contemporary iconography.

[pull_quote id=”4″]

I think the way that a lot of fans around the world venerate the stars of music, movies and sports, with their personal iconography of posters and pin badges, raise these celebrities to a super-human, god-like status. So this kind of worship of real people is certainly not something relevant only to China.

Mao impersonator featured in the documentary Readymade by Zhang Bingjian (read more)

Early in the book you mention the Cultural Revolution, a period during which much of China’s religious infrastructure was systematically destroyed. You say that religion, or the innate desire to create and worship deities, never went away. How did people maintain faith or belief during such a tumultuous period of China’s history?

The Chinese are a passionate and emotional people who’ve been through a lot. They are always looking to entrust their hopes and fears in some external, higher spirit. I don’t think you can stop people from having faith, only perhaps change its focus. Around Mao’s time, the majority of people were very invested in the idea of the new China, formed after Communist victory in the Civil War. It’s something that really comes through in the kind of fervent optimism that pervades film and art during the 1950s. That peace and seeming prosperity lasted for about a decade. Then there’s the cult of Mao, which, as we have seen from history, proves that faith can cause destruction as well as hope and creativity.

Now that China is relatively more open, and more prosperous, do you think belief has taken a new form in the country? Is there an increased focus on some gods — of wealth, for example — over others in this era?

There definitely has been a resurgence of spirituality in this more open and prosperous China. I’m noticing several strands. With a need to reconnect with roots and heritage, and with China’s new-found confidence in its place in the world and therefore in its own culture, there is definitely an increased veneration of deities that represent indigenous Chinese civilization, such as creator gods Nüwa and Pangu, and Huangdi, the legendary founder of Chinese civilization. The traditional staples — such as Fu Lu Shou, the gods of happiness, Wen Chang, god of scholarly success, and as you say, Cai Shen, the god of wealth — are all still doing very well, understandably.

In terms of forms of worship, that has become a lot more commercial, in the sense that imagery of these deities is being used in branding and advertising. There is also a lot of corporate involvement, with companies paying collective tribute, and even holding events on feast days. Another new area of veneration is one that has developed with the flourishing of China’s MMORPGs [massively multiplayer online role-playing games]. Currently, domestic video games enjoy huge popularity, and online communities are ever-growing. Older deities such as the gods of the elements, with their alternative beast forms, have become beloved avatars and supporting guides for China’s gaming youth.

Finally, the protectors, which make up a big section of my book, have always enjoyed a lot of veneration. China is changing at an astonishingly fast pace, and people are feeling the need to seek help from guardian spirits. There are many protector gods of various kinds to choose from in the Chinese pantheon.

[pull_quote id=”5″]

What does one stand to gain in their understanding of today’s China by reading your book?

First of all, I hope they will enjoy the book. For anyone seeking to understand alternative religions and Chinese spirituality, I hope to have provided them with an accessible and open-minded introduction that also conveys the depth of the subject, and points them in directions they could investigate, should their interests take them.

I have written about how every single deity featured in the book has evolved through time, and their place in contemporary society. China’s spirituality is intimately connected with the land, the mindset, the society, and the daily lives of its people, and therefore inseparable from its culture. I hope that those interested in China will be able to make more sense of its complex cultures through my book.

China is a civilization with a fundamentally different outlook, set of aesthetics, and ways of thinking than the West. Creatures that symbolize evil in Western culture, such as bats and spiders, are auspicious in Chinese culture. And the Western idea of the purity of white clothing is reversed, as it’s a funereal color in China. I hope that anyone working with China in any way will find this book useful as a guide to understanding the country and its people.

As a writer based in the UK with a long history of covering Chinese myth, have you noticed a shift in the average English person’s perception of China or Chinese culture? What do you think are the major misunderstandings about Chinese culture that still persist in the West?

I think the average Western person used to be afraid of China because it felt alien to them, but now, with China wielding immense economic power, they’re terrified. A lot of that comes out in some quite ingrained racism, labelling every bit of macro-governance as human rights abuse, and seeing every product stamped with “Made in China” as a soulless copy-cat product, or shoddy goods churned out cheap enough to run everybody else out of jobs.

China isn’t a dragon that’s going eat their countries, and whilst that monoculture view of China does make it look like a large, scary economic powerhouse, China is no longer the same country it was 20 years ago. Every day we are seeing a little more progress, towards a more secure, balanced, greener society in the making. The first laws protecting the environment, charities, the disabled, and LGBT groups have all been passed in the last decade or so. With so many innovations on individual and commercial levels, in all kinds of designs, technology, and sciences, China is also developing the breathing space to explore its social responsibility, alongside its spirituality. What is needed at this point, from everybody, is a great deal more understanding.

—

From Kuan Yin to Chairman Mao: The Essential Guide to Chinese Deities is out on June 1 in the US, available in paperback and e-book formats from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and IndieBound. It can be pre-ordered now for a July release outside the US, and will also be available in select bookstores in the US and UK.

You might also like:

The Four-Year-Old Chinese Animation Studio That’s Putting Out Films on the Scale of PixarArticle Sep 29, 2017

The Four-Year-Old Chinese Animation Studio That’s Putting Out Films on the Scale of PixarArticle Sep 29, 2017

Watch: Lu Yang’s Virtual PantheonArticle Nov 04, 2017

Watch: Lu Yang’s Virtual PantheonArticle Nov 04, 2017