On Sunday, July 12, 2020, in partnership with Black Livity China, RADII hosted a live chat on our Instagram between hip hop artists Bohan Phoenix and MC Tingbudong.

Since the start of the latest Black Lives Matter protests in the US and around the world, discussion has swirled for weeks in both the media and on online platforms in mainland China.

Within the country’s hip hop community — which owes a huge debt to the genre’s origins in Black culture — reactions have varied widely. Some of the most famous rappers from China have been largely silent on the issue, while others have been passionately outspoken. And beyond the world of hip hop, the movement has raised many questions around Asian communities’ support of Black Lives Matter.

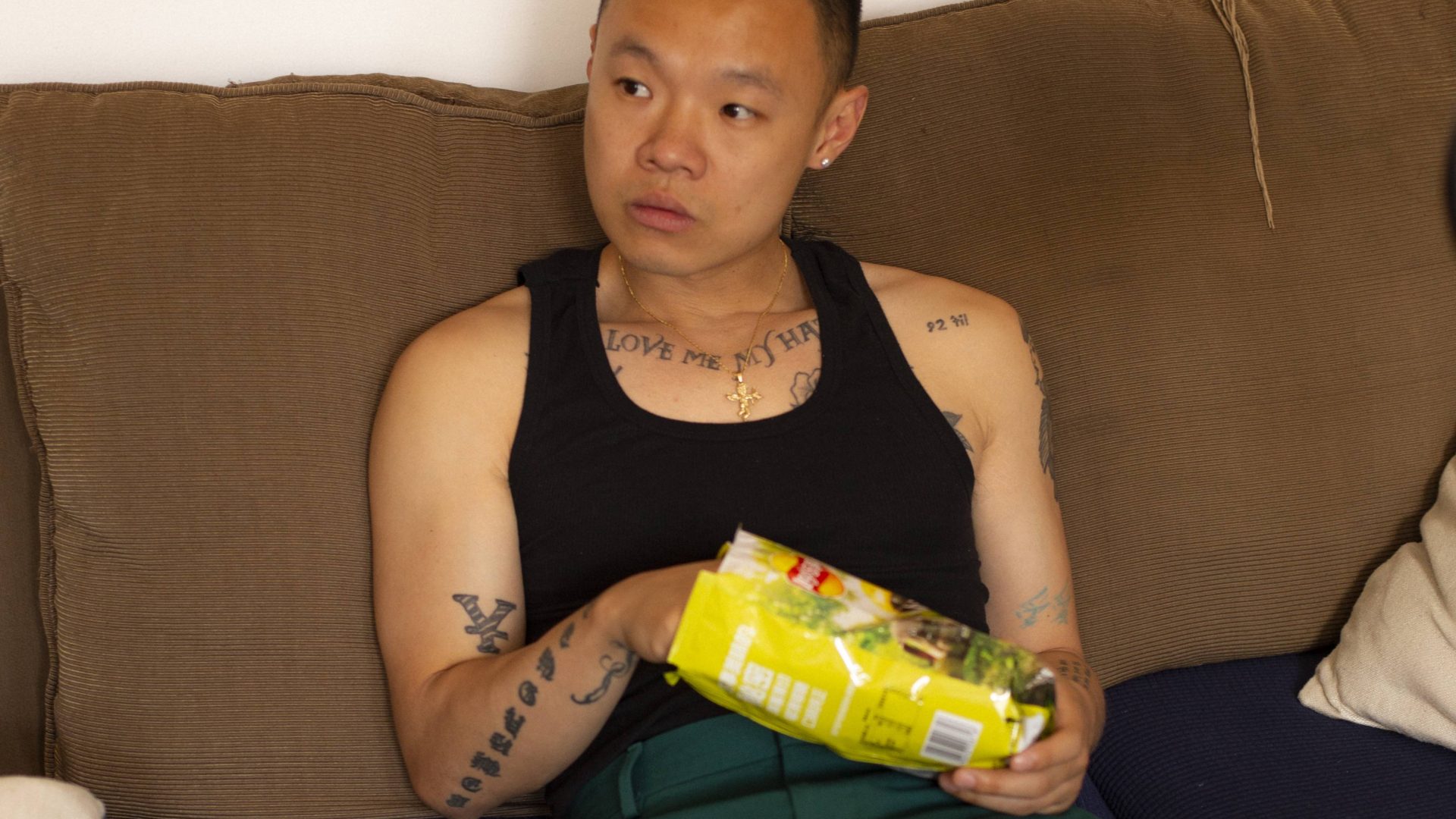

Born in Hubei province in China and raised in New York, Bohan Phoenix is an acclaimed bilingual rapper who has worked with the likes of Higher Brothers and Vava. MC Tingbudong (aka Jamel Mims) is a Washington DC-born rapper, poet and activist who became a key part of the late ’00s Beijing hip hop scene after spending a year in the Chinese capital through a Fulbright scholarship.

Below are some edited text highlights from their conversation, while you can watch the full video right here:

On the Black and Asian Experience

Bohan Phoenix: I think I got into hip hop before I even spoke English. You know how people say that when you learn a new language, you think differently? It rewires your brain. Through the language of hip hop, I was thinking differently.

So I was showing up to schools, young, with durags, dressed like Eminem — I drew tattoos on my arms, you know? Other Asian kids didn’t really understand me, and obviously the white kids didn’t understand me. They just thought I was acting hard and being weird.

It was the gospel choir that really showed me the power of music. Before that I was a fan — I was studying, imitating… but it was gospel choir that really made me connect with the black experience. The family unit, the food, a lot of things that we hold as valuable [in the Asian community].

On Black and Asian Communities

BP: Before coming back to Boston [the last few days], I was in New York, too. I was hitting the streets, protesting, and I was seeing people holding up signs. One of the signs said Immigration Act of 1965. I’m in the middle of a protest, and I’m Googling it. I’m looking at it and I’m like oh shit. This is an act that Black people fought for during the Civil Rights Era, that literally allowed more Asian people to immigrate to the states. Black people literally fought for my right to be here.

Jamel Mims: [In that time] you actually had revolutionary China as a beacon on the map, where they’d ended the food crisis, taught ethnic minorities their own languages in schools for the first time, ended prostitution […] and so this was actually a real challenge to the US.

The Black Panthers in the ’60s were taking leadership from a Chinese dude across the ocean named Mao. You had W.E.B. Du Bois and other delegations of Civil Rights activists making trips to China. You had Chairman Mao giving correspondence to Civil Rights leaders, and calling out the US as the worst race-based caste system in existence on planet Earth.

There’s a shared history of revolutionary culture and struggle. Shit, you know the dice game Cee-lo? I realized, this game Cee-lo that everyone plays in Harlem is the Chinese game siwuliu. It’s like, for real, these communities have been side-by-side, but they’ve been divided again for explicitly political reasons.

Related:

From W.E.B. Du Bois to the Panthers: A History of Black Americans in ChinaBlack Americans have been developing connections with China since the 1930s, well before the founding of the People’s RepublicArticle Feb 27, 2019

From W.E.B. Du Bois to the Panthers: A History of Black Americans in ChinaBlack Americans have been developing connections with China since the 1930s, well before the founding of the People’s RepublicArticle Feb 27, 2019

On the Ability to Change

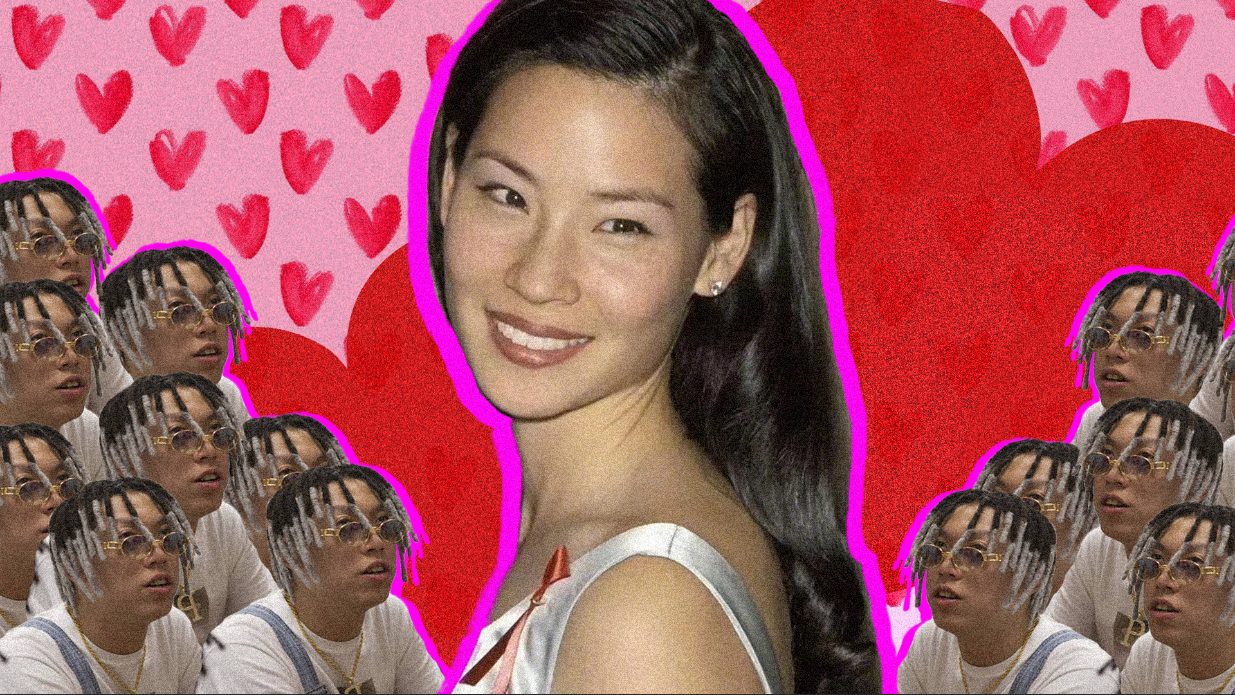

BP: Here’s a story about my aunt. She lives in Chengdu, that’s where me and my boys stay when we’re on tour in China. What she knows about Brooklyn is based on the Western narrative that flows over, and she absorbs it from the media that Brooklyn is a hei ren qu [黑人区]. What’s that?

JM: That’s a “black person’s area.”

BP: Exactly. So to her, Brooklyn is scary. Because to her, black people are scary and bad. And to her, they’re bad because they’re black and it’s ingrained in them. And that’s why even though they’ve been in America for two or three hundred years, they can’t get the same jobs because they’re naturally lazy and bad.

She would ask me, are you safe living in Brooklyn? Do black people bully you for making black people music?

There’s no photos or videos, or history lessons I can give her to let her know what it’s like, because she’s never met or interacted with a black person, or even seen one in real life. So I’m on tour, and Jachary and Ralph are staying with my aunt. The five of us are staying at my aunt’s house, and Ralph is like 6’3″, 260 pounds, laid out on the couch in his underwear for a whole week.

JM: Because it’s hot as hell in Chengdu.

BP: It’s hot as hell! And at the end of the week, my aunt is in love with him. At the end of the week, she’s like “Jach!” “Raph!” because she can’t say the “l.” She’s in love with them.

In China, we live in all these communal areas, like Stuytown in New York. People see her walking out with these two black dudes, and they hit her up on WeChat like, “Who are these black people? Scary,” blah blah blah. And my aunt is sending them videos of Ralph posing like this:

Took hundreds of fans calling out 88 on IG but finally they took notice & this is why it’s urgent they take action: Hip Hop artists & fans in China needs to know the history and context of the black experience to help in a meaningful way and 88 has the resources & responsibility pic.twitter.com/qFFEWksnjA

— Bohan 博涵 (@BohanPhoenix) June 5, 2020

She never had a chance to be educated, you know what I mean? I think although there’s a lot of flagrant racist shit happening in China, there is a better chance to educate them than certain white people in America who are ingrained with hatred.

On the Model Minority Myth

BP: The model minority myth was created in the ’60s, after the Japanese concentration camps. They created this idea that you can be a model minority if you work hard, study hard, shut the fuck up, don’t criticize the white man, and listen. Then you can be successful.

So they use this to drive a wedge between the Asian communities and other people of color. To be like, see? Y’all could be like the Chinese folks, if y’all just blah blah blah.

The thing is Asian people ate that shit up. It’s because of our families, our grandparents and the people that made it here after the war. They just wanted to be white. They wanted to fit in, they changed their names to Mike or Steve.

While I’m out there on the streets protesting, I’m seeing 50 and 60-year-old Black men and women, and I realize that activism gene — it was never passed down in the Asian community. Our parents and grandparents were happy to chill. They were like, “well you know, we finally got a job now.”

On Being Black in China versus in the US

BP: Tell me, you spent a lot of time in China back in early 2000s or later 2000s right? Tell us a little about that, I feel like, the Black experience in China.

JM: So you know in 2008, I got a Fulbright scholarship to study hip hop in China, and so I was there in ’08 around the time of what’s heralded now as like the Golden Age of hip hop in China. A lot of what was going on was rap battles like every night, where you would have folks in places like [live music venue] Yugong Yishan, and different nights or battles like [cypher event] Section 6, and what I really found there was a community that was rooted in hip hop. Where it was really about how well you could freestyle and how well you could either ma ren [骂人] or insult the other person.

There was this real rebellious spirit about it, right? People were like, “fuck school!” You were gonna have to learn what you need to learn in the world. So a lot of that is where I found community. Since then, a lot of that in 2014 and 2015 had come under political targeting — my homies in Yin San’er [In3], their music was placed on banned lists and things like this. But a lot of that set the groundwork for what exists now in the hip hop community in China. But as a Black person I really did find my community. It felt like I was walking down in Harlem or in New York City with homies I would bump into, you know?

Related:

“I’m a Hustler”: After Being Banned, Beijing Hip Hop OG Jahjah Way is Building a New Community“We used to be on the street, but now street culture is not on the street, it’s only on the screens. This is a problem.”Article Feb 26, 2020

“I’m a Hustler”: After Being Banned, Beijing Hip Hop OG Jahjah Way is Building a New Community“We used to be on the street, but now street culture is not on the street, it’s only on the screens. This is a problem.”Article Feb 26, 2020

BP: That’s funny cause when I was back in China on tour with Ralph and Zach, and they were like, “Yeah we stand out so much in China but we feel so safe.”

JM: Yeah. We shouldn’t romanticize it, there was still a commercial element. But there was no mainstream culture, right? In a huge way. There wasn’t an industry, there weren’t managers, there weren’t giant tours, there weren’t concerts, festivals. So the people who paid attention to it or participated in the subculture, there was a bit more of an informed audience.

BP: Right. That type of curiosity, where it leads them to come up and say, “Hey, I wanna know more about what you are!” To me, I’ll take that type of ignorance any day over, “Stay the fuck away from me.”

JM: Yeah, there’s a bit of a difference there. I’ve had literally more times than I can count, and this happens in both America and China, if I’m walking behind someone and they suddenly notice me it’s like, “Ah! Xia si wo le!” (“You scared the shit out of me!”) And I’m like, why? And so there is a lot of that, or ogling, or people following you around in stores.

But in China it’s not backed by state power. There might be individual actors and even some malevolence there, but it’s not backed by state power. But white supremacy is actually pervasive throughout capitalism and imperialism. And we’re a global system now. So you’ll see skin whitening creams in China, and you’ll see advertisements for Hei Ren Ya Gao, which is Darlie Toothpaste, Black Man Toothpaste, which [was originally called] “Darkie Toothpaste.”

Related:

MC Tingbudong Wants Chinese Hip Hop to Find its Place in the World“I felt like I was like being offered the chance to participate in the era of hip hop I had so revered during my upbringing”Article Feb 11, 2019

MC Tingbudong Wants Chinese Hip Hop to Find its Place in the World“I felt like I was like being offered the chance to participate in the era of hip hop I had so revered during my upbringing”Article Feb 11, 2019

On the Responsibilities of Chinese Hip Hop Artists

BP: One of the things I’ve been putting my neck out for is encouraging companies like 88rising, encouraging big artists like Kris Wu and Higher Brothers and Vava [to do more].

As rappers, we’re the narcissists — we’re out here like, look at us and listen to us, we have a voice. So I’m encouraging these cats because at a time like this, they represent the Asian community whether we like it or not.

Personally I’ve gained so much from hip hop over the years. I’ve gained my confidence, I’ve gained my identity. I’ve gained philosophy and values that I still live by to this day. I’ve gained friends, I’ve traveled from music, [the list is] endless. And then there’s the monetary value. There’s so much before the monetary value that money couldn’t have even bought…[88rising] donated 60,000USD, that’s like half of a Higher Brothers show.

The money will help, but y’all have the resources to educate hip hop fans in China. I’m sure you’ve seen on Weibo — hip hop fans in China love hip hop, but they’ll say some nasty shit about black people, you know what I mean? Instead of focusing on donating money, you guys should educate these fans so they can become voices of reason for the people around them when they say nasty stuff, like “That guy’s music is so good, but I can’t touch them.”

On Chinese Hip Hop Then and Now

JM: We’re living in China, we’re living in the consequences of that Golden Age I told you about, that frankly was persecuted by the state and then sanitized into a more commercial-friendly version of hip hop, which then spread after 2015. It was Rap of China, and then ‘17, ‘18, and ‘19, to have uninformed audiences and then you have the consumption of hip hop happening at a mass scale.

There’s actually some knowledge of what an MC is, but as far as the political duty of an MC that you’re speaking to — you called it narcissism, but that’s actually very much rooted in the fact that MCs were in the streets telling the truth. And that is absent from the picture in a mass way in popular Chinese hip hop culture.

Related:

China’s Biggest Rappers Were Quiet on Black Lives Matter, But Real Hip Hop Artists Stood UpWhile the Higher Brothers were criticized for their lack of action, a number of China’s underground rappers spoke out on Black Lives MatterArticle Jul 10, 2020

China’s Biggest Rappers Were Quiet on Black Lives Matter, But Real Hip Hop Artists Stood UpWhile the Higher Brothers were criticized for their lack of action, a number of China’s underground rappers spoke out on Black Lives MatterArticle Jul 10, 2020

BP: It’s commodified as something to be cool with. It’s very much a one-sided thing. Again, I wanna make it clear, I’m not calling to cancel 88. I’m not calling to cancel none of these artists. It more of like encouragement and like you said, critique. The other day I did the numbers — Kris Wu, Jackson Wang, 88, and the top three Rap of China contestants altogether have over 20 million reaches and followers. That’s off Instagram alone. That’s not even counting Weibo — that would probably be in the hundreds of millions.

JM: It’s conversations like we’re having in this space, but really it is something that is gonna have to be pushed, in a large way, from the bottom, from the fans themselves, from the people who feel attracted to this music, who feel attracted to the culture. You have whole generations of kids in China right now, Generation Z, young people who grow up with their favorite hip hop artists who are trying to be artists, and some of these artists like I’m thinking Kafe.Hu, people who know their shit. I think it’ll actually take a movement of artists and fans, like what you’re doing in particular to call these other artists out, who also bring their audience into the fight. That’s the main way that people get educated.

You can follow Bohan Phoenix and MC Tingbudong on Instagram. Black Livity China is an online platform documenting 360° of Black experiences both in China and in relation to China for the benefit of our global community