Chinese Rap Wrap is a RADII column that focuses on the Chinese hip hop scene, underground or in the mainstream.

In mid-June, Jamaican-British producer and DJ HARIKIRI, a frequent collaborator with the likes of Higher Brothers and Chengdu Rap House, talked about how he was rejected for a ride by a taxi driver in Beijing because of the color of his skin in an interview with legendary Chinese hip hop podcast The Park (嘻哈公园).

After talking about the incident, however, HARIKIRI added: “I will definitely say that overall China is way more chill than the West because people here aren’t systematically pre-disposed to be against foreigners, in particular Black people; the white world is totally different.”

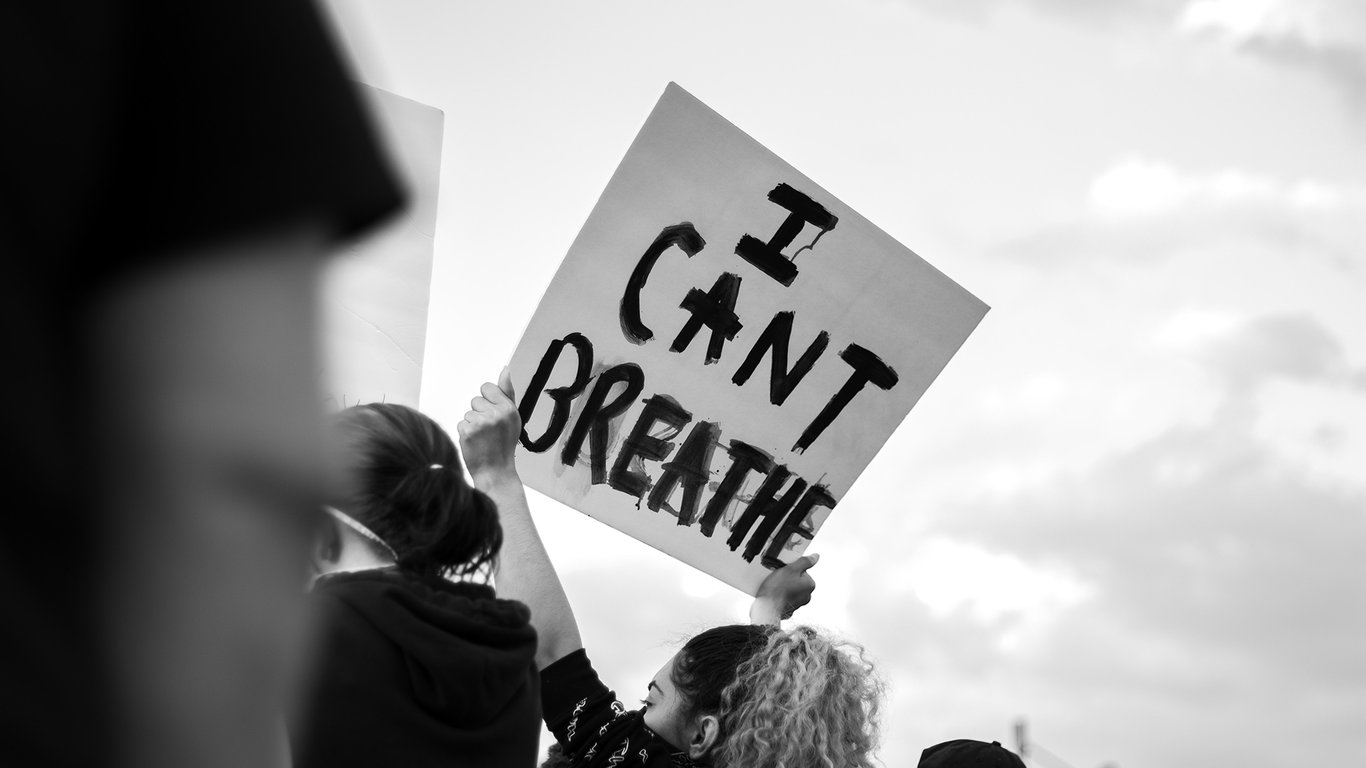

The producer was discussing racism in China in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted across the US following the killing of George Floyd. That movement prompted some shows of solidarity on social media from Chinese rappers, but also sparked accusations that such figures were not doing enough to educate their audiences on the debt owed to Black culture by hip hop artists.

Was this calling out justified? Should Chinese hip hop artists be more vocal about supporting anti-racism movements in the US and the rest of the world given the genre’s roots? Did the distinctive environments HARIKIRI referred to on The Park impact some individuals’ responses?

Racism in China

Over the course of 2020, issues of racism particularly towards Black people in China have been prominently displayed.

Only two months ago, anti-Black sentiment reared its ugly head during a minor outbreak of Covid-19 in Guangzhou. Widely disseminated news about the eviction of African tenants in the southern city led to headlines around the globe about the treatment of Black people in China.

Related:

China’s African Communities Suffer as Covid-19 Fuels Anti-Foreign SentimentIn Guangzhou, stories of displacement and discrimination toward Africans are becoming more frequentArticle Apr 12, 2020

China’s African Communities Suffer as Covid-19 Fuels Anti-Foreign SentimentIn Guangzhou, stories of displacement and discrimination toward Africans are becoming more frequentArticle Apr 12, 2020

But such issues are not limited to anti-foreigner sentiment. Black and bi-racial public figures in China, such as variety show star Zhong Feifei and former national team volleyball player Ding Hui, have been plagued by hateful comments on social media throughout their careers.

Alan Xue, a 32-year-old screenwriter who is of the Hui minority — a predominantly Muslim ethnic group largely residing in the northwest of China — feels that cultural clashes are more likely to happen when a larger proportion of the population is in conflict with the predominant Han Chinese ethnic group. “There is a Hui exclusive circle in Ningxia [Hui Autonomous Region] where there’re enough Hui people, so there is conflict between the two cultures there,” he says. “If 13% of the Chinese population is a minority group, and they want to keep their own lifestyle, there will be conflict immediately.”

Despite numerous ethnic minorities being present in the country, China’s population is overwhelmingly ethnic Han. And there are only around 1 million documented expats living in China (equivalent to about 0.7% of the Chinese population).

As such, conversations in the US and the rest of the world about Black Lives Matter can feel removed for the regular person. For the majority of the population, discussions around the subject are likely to be met with comments such as, “why do you bother to meddle in others’ business?”

Related:

To Chinese in America: Black Lives Matter Is Our Fight TooIn response to the latest Black Lives Matter protests, Chinese and Chinese American debates fixate on a very narrow definition of fairnessArticle Jun 12, 2020

To Chinese in America: Black Lives Matter Is Our Fight TooIn response to the latest Black Lives Matter protests, Chinese and Chinese American debates fixate on a very narrow definition of fairnessArticle Jun 12, 2020

For Chinese rappers and hip hop musicians, however, the response, or lack thereof, has garnered disappointment from the international community.

Chinese Rappers Speaking Out

Much of this criticism has focused on groups such as Higher Brothers, who are the most famous hip hop artists from China. When we reviewed Masiwei’s solo album release earlier this year, we were taken aback by the lack of any real substance in his music. As such, we weren’t particularly surprised at his and his bandmates’ failure to speak out on such a substantial topic as Black Lives Matter.

Related:

Chinese Rap Wrap: Higher Brothers’ Masiwei Drops Loved Up Solo AlbumPlus plans for the new season of “Rap of China” get “leaked,” key crew GO$H drop a new cypher, and moreArticle Mar 05, 2020

Chinese Rap Wrap: Higher Brothers’ Masiwei Drops Loved Up Solo AlbumPlus plans for the new season of “Rap of China” get “leaked,” key crew GO$H drop a new cypher, and moreArticle Mar 05, 2020

Masiwei and the other Higher Brothers posted an English-language message crafted by label 88rising over their Instagrams, but have otherwise shown limited engagement with Black Lives Matter or the issues the movement raises. As the most prominent Chinese hip hop group, they have become something of a focal point for criticisms aimed at rappers from China.

A little update regarding the future of this account. We hope that you guys can continue trying to educate your favorite artists, donating to funds, signing petitions & raising awareness.

Thanks for a good almost two years, @rapofchina signing off for now ✌️ pic.twitter.com/PYVS6nCegt

— RISING! CHINESE HIP HOP (@rapofchina) June 8, 2020

Popular Twitter page RISING! CHINESE HIP HOP declared itself so disappointed by the response from Chinese artists that it decided to suspend its account, unable to square the promotion of Chinese hip hop with the tepid response of numerous artists to Black Lives Matter.

Chinese-born, US-based rapper Bohan Phoenix was particularly vocal, writing on Instagram, “You have the resources and responsibility to start this education.

“Lead by example and stop spreading ‘hip hop culture’ without showing the proper respect and acknowledgement for the communities that suffered to create it.”

Similarly, an article by former RADII Culture Editor Josh Feola in Variety pointed towards the slow nature of the response and support from Asian American label 88rising, which has benefited off Black culture for years.

The anger over the inaction of certain musicians can also be intertwined with an ongoing discussion in the Chinese hip hop community, in which some performers have been designated as “hip hop artists” and others as “rappers.” Earlier this year, when we spoke with Jahjah Way, one of the founders of legendary and formative rap group in3, he expressed disappointment with the current hip hop and rap community, saying:

“We used to be on the street, but now street culture is not on the street, it’s only on the screens. This is a problem.”

Related:

“I’m a Hustler”: After Being Banned, Beijing Hip Hop OG Jahjah Way is Building a New Community“We used to be on the street, but now street culture is not on the street, it’s only on the screens. This is a problem.”Article Feb 26, 2020

“I’m a Hustler”: After Being Banned, Beijing Hip Hop OG Jahjah Way is Building a New Community“We used to be on the street, but now street culture is not on the street, it’s only on the screens. This is a problem.”Article Feb 26, 2020

His comments, as well as the story of Jahjah Way and his formative rap trio in3, help shape another picture of an increasingly commercialized, apolitical hip hop landscape in China. “If people in China introduce me as a rapper, I would say ‘why do you scold me like that?’” Way told us, echoing the feeling of a schism in the Chinese hip hop community, where the word “rapper” has come to represent something related to “surface, superficiality and exaggeration.”

LA-based, Chengdu-born hip hop musician PO8 brought up this fundamental difference among rappers on Chinese social media platform Weibo after the protests: “I’m just saying it to people who work with hip hop, and it’s normal that not everyone can be sympathetic. There’s no need to fight against each other.

“When we’re consuming a culture, we just easily forget the nature of it; but as people who inherit and lead it, we cannot forget.”

Unfortunately, this is the sense we get from an increasing number of Chinese hip hop projects: too often, such releases are commercial, surface-level and without substance.

Related:

The History of Rap in China, Part 1: Early Roots and Iron Mics (1993-2009)No, it didn’t all start with The Rap of China — far from it. In Pt. 1 of a two-part series, Fan Shuhong traces the history of hip hop in China from the 1990s to 2010Article Feb 01, 2019

The History of Rap in China, Part 1: Early Roots and Iron Mics (1993-2009)No, it didn’t all start with The Rap of China — far from it. In Pt. 1 of a two-part series, Fan Shuhong traces the history of hip hop in China from the 1990s to 2010Article Feb 01, 2019

To group all Chinese hip hop musicians under the same umbrella, however, is unfair. Many passionate hip hop lovers, some of whom operate in the underground, have been speaking to their fans through their social media accounts.

Deeper Underground

For example, well-known Guangzhou hip hop nerd AR spoke out on Weibo, writing, “Rap music described lots of stories about how Black people were treated unfairly by American police. We should not only speak up about injustice, but also make a change.” The respected underground rapper has been vocal with his disdain for other artists seeking commercial gain without educating themselves on the genre, with lyrics such as, “Chasing that clout won’t get you anywhere / Bro listen, bring the hip hop back.”

Related:

Chinese Rap Wrap: AR Puts Clout Rappers on Blast with “Pop Rap”“Just sing Chinese like it’s English / Then add some bad English in the Chinese bars / They’re made for foreigners so it doesn’t matter”Article Dec 04, 2019

Chinese Rap Wrap: AR Puts Clout Rappers on Blast with “Pop Rap”“Just sing Chinese like it’s English / Then add some bad English in the Chinese bars / They’re made for foreigners so it doesn’t matter”Article Dec 04, 2019

Elsewhere, popular diss king Kindergarten Killer dropped a pro-BLM track, “I have a dream,” that sampled Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic 1963 speech.

Saber, a member of boombap crew Dungeon Beijing signed to music label Modern Sky, dropped a single “We Are Hip Hop,” and wrote, “In the year of 2020, the world changed, no matter if it’s in our country or on the other side of Pacific. Maybe I would know nothing if I were an ordinary person, and would not be supposed to make any comments.

“But as someone engaged in hip hop, I, we, should speak up for the culture that we’ve been soaking up for years, or for our fellow people who are struggling at the bottom of society.

“To think bigger, it’s our responsibility because we have the capacity.”

Beijing DJ and rapper Nasty Ray, meanwhile, dropped a mixtape in support of Black Lives Matter. The tape features musical styles such as boombap, hardcore rap, trap, and g-funk. The release acts as a way for Nasty Ray to get messaging around the issue out to his fans in China.

But while parts of the community are educating fans on the legacy of Black music and what that means in China, there needs to be more acknowledgement especially from a younger generation of hip hop musicians who have increasingly turned to making shallow raps centered around money, sex, and fame.

As Jahjah Way told us in his interview, “I can feel that a lot of people are starting to discover it now, but how to see it right? In China it’s just viewed as a market. All they see is how many young people are consuming it, and that’s the only reason why they’re doing it. They view hip hop as an investment market, and besides money, dignity can also be the cost. But when there was nothing like this, we were already doing it. We don’t want to see young people say they love street culture because of profit.”

Related:

Beijing Rapper Saber on the Hip Hop Wave, and “Rap of China” from the InsideArticle Jul 31, 2018

Beijing Rapper Saber on the Hip Hop Wave, and “Rap of China” from the InsideArticle Jul 31, 2018

With the explosion and commercialization of hip hop music in China, a fundamental question remains: are you really making hip hop? Or are you just using rap skills to quickly gain money and fame, just because it’s trendy? It’s a strange time for hip hop music in China, and sometimes hard to determine who is real and who is fake. But only time will tell.